By Rick Montgomery, The Kansas City Star

I wasn’t all that stupid when, at age 25, I came to Kansas City to work for The Star. Really, I had nailed near-perfect scores in American history back in the 11th grade, although I think the textbooks misguided me.

Those color-coded maps of the states’ allegiances during the Civil War showed both Missouri and Kansas as blue. They were on the same side, no? Confederate gray covered the region south of the Mason-Dixon Line, where the fighting, I thought, first erupted – in 1861 of course. Nowhere had I read that the hostilities started several years earlier here on the Missouri-Kansas border, with fledgling Kansas City caught in the crossfire.

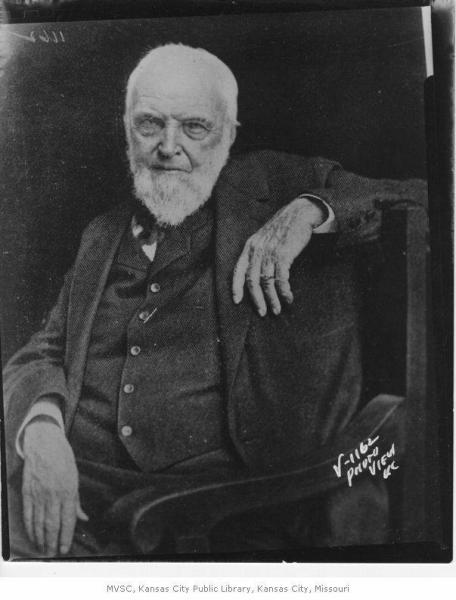

Upon arriving in 1986 as a native Iowan, I knew one thing about Kansas City area history, and that was Harry Truman. My father and I had visited the presidential library en route to Royals games in the 1970s. Somewhere I would read that parts of the well-traveled Truman Road were once named after a fellow newspaper man and mayor of Kansas City during the Civil War, Robert Van Horn. Truman himself expressed regret at the street’s renaming, as it erased from the local map an early town booster who had lived to age 91 and ranked among the most game-changing Kansas Citians of all time.

Divisions Still

Beyond my interest in learning more about Van Horn, I was struck early on by what seemed to be bad blood between Missouri and Kansas. College rivalries between neighboring states – fine. But I had come from a bi-state community, the Quad-Cities straddling Iowa and Illinois, and the biases there were positively quaint by comparison. I do not recall anyone refusing to cross the state line to shop at a mall, hunt for a home or send a kid to college, as more than a few do around here.

Then again, I was not sure what “Bleeding Kansas” meant or why a cannon stood in Kansas City’s Loose Park. I later learned that the cannon marks the spot where Confederate Major General Sterling Price commanded his Army of Missouri in the decisive 1864 Battle of Westport, sometimes called the “Gettysburg of the West.”

Hearing of the Battles of Westport, Lexington, Lone Jack, and Mine Creek, I once presumed these were measly affairs that resulted, perhaps, from Confederate troops taking a wrong turn in Arkansas.

A fuller yet infinitely complex story would emerge from wondering: Why did Little Dixie battle flags still flap in some Missouri cemeteries? What on earth was a jayhawker? Or a bushwhacker? The name “Quantrill,” for some Missourians, evoked a legacy almost equal to that of the raging abolitionist John Brown on the Kansas side.

A group of history buffs known as the Civil War Round Table of Kansas City—which hosted former President Truman at its first downtown banquet in the 1950s—began to splinter in the 1980s, not long after electing to move its monthly dinners to a country club in the Kansas suburbs. Enthusiasts on the Missouri side broke to hold meetings of a less formal, Southern flavor in Independence.

From reporting on the 1995 bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, I was informed that Timothy McVeigh’s crime might not have been what news outlets then called the deadliest act of terror on American soil. Local historians pointed to something ghastly that visited Lawrence, Kansas in 1863. Between 160 and 190 men and teenaged boys died at the hands of Missouri guerrillas on horseback, led by William Clarke Quantrill, a one-time schoolteacher turned vigilante. I was among the Kansas Citians who lined up at theaters to watch “Ride with the Devil,” film director Ang Lee’s 1999 movie that included a depiction of the massacre.

General Order No. 11, issued by General Thomas Ewing from his headquarters in today's River Market area, forced rural Missourians on the Western Border out of their homes.

For generations, the Union’s response to Quantrill’s assault would go unmentioned in many formal accounts of Civil War history: General Order No. 11, issued by General Thomas Ewing from his headquarters in today’s River Market area, forced rural Missourians on the Western Border out of their homes. They left behind the “Burnt District,” characterized by towns torched and livestock taken by Kansas marauders.

About a decade ago, the embers of regional animus glowed once more. Kansans seeking to promote the 150th anniversary of the 1854 establishment of Kansas Territory asked Congress to grant the eastern third of the state special designation as a national heritage area, to be labeled “Bleeding Kansas.” Congressmen from Missouri disapproved; they wanted the name changed and demanded their counties not be left out. Heated meetings produced a national heritage area called “Freedom’s Frontier,” spanning 41 counties in both states. It is billed as “a testing ground for debates concerning rights, freedom, and their meaning in the American democracy.”

The history behind all of this speaks to divisions that persist in the Kansas City area. Any athletic matchup between the Missouri Tigers and the Kansas Jayhawks has long been hyped a “Border War,” even if the national broadcasters covering the games often do not know why.

Upstart Kansas City

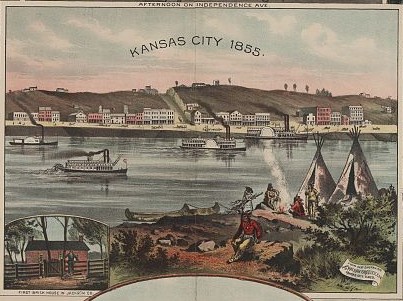

It is hard to fathom how the Town of Kansas—originally founded in 1838, incorporated in 1850, and later to be officially renamed “Kansas City” in 1889—made it through the mayhem. After all, the community of about 2,500 was still in its infancy when tensions erupted over slavery’s future.

Under a system of “popular sovereignty,” the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 empowered settlers in those territories to choose for themselves whether or not to expand slavery west of Missouri. The law reneged on the earlier Missouri Compromise, which had prohibited slavery in the Western territories north of the 36°30' north parallel. Outraged abolitionists in the East saw but one course of action: to hurry west and stake claims in Kansas.

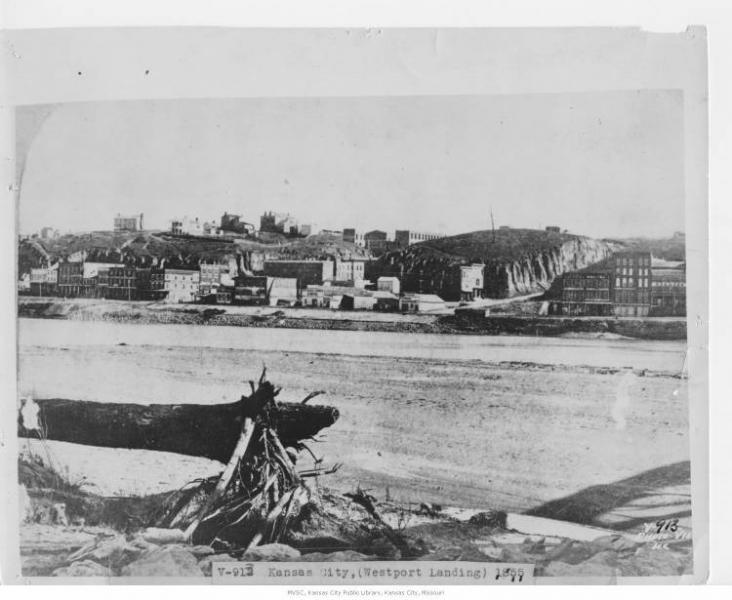

For settlers headed to Kansas or further west along the California, Santa Fe, or Oregon Trails, the westernmost railroad only extended to St. Joseph. Many settlers traveled from there on the Missouri River and arrived at the Town of Kansas, or “Westport’s Landing” at the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri Rivers, where the founders of the future Kansas City hoped to benefit from traffic heading west.

Passers-through quickly noted that the more established outfitting village of Westport, to the south, was a “hot bed” of proslavery types, where at times “no Free State man was safe in passing,” as one visitor wrote. About two-thirds of the households of western Missouri in the 1850s had members originating from slaveholding states. But in the summer of 1854, hundreds of antislavery stalwarts of the New England Emigrant Aid Company began to flock in, including future town builders such as Kersey Coates. Eventually, thousands would venture into Kansas Territory to settle, if only for a few months, and then cast their ballots for freedom.

Missourians crossed over to stake claims, too, and enough were armed to seize polling places, interfere with Free-Staters’ votes, and illegally cast their own ballots in March 1855 to establish what the antislavery side called the “Bogus Legislature.” The ruffians organized in communities we know today as fun places to meet friends: In Parkville in 1855, they tossed the press of an antislavery newspaper, the Industrial Luminary, into the Missouri River. From Westport, they hauled cannons into the abolitionist stronghold of Lawrence and blew down the Free State Hotel in 1856.

In the center of the chaos sat upstart Kansas City. Its population ticked toward 4,500 in the late 1850s despite the bleeding in Kansas and the stealing out of Missouri. Town officials of Northern and Southern backgrounds welcomed more than 700 steamboats unloading at the levee in 1857. One newcomer was Theodore Case, a future postmaster who would recall a gully town replete with “red shirts, bowie knives and pistols openly worn at the girdle.”

Local businesses just wanted to make a buck. Kansas City mayors would toggle between Democrat (whether pro- or antislavery) and Republican. Mayor John Johnson held office just 35 days before giving in to his wife’s urging that they flee the danger in 1855.

Far more successful was Robert Van Horn, a transplant from Ohio who established the Western Journal of Commerce and by 1860 became the town’s leading publisher. Unrelenting in his boosterism, Van Horn’s paper lamented that border parties “have concluded to go to war to settle their difficulties by bloodshed. (But) we wish to remind them that they can buy powder and lead of (local) merchants at St. Louis prices, and other military supplies much cheaper.”

Kansas Territory eventually quieted. Enough Free-State supporters settled—alongside apolitical arrivals just wanting to set up ranches or shops—to fend off interference from Missouri ruffians. But by 1861, with the start of the Civil War, hostilities would erupt as never before. Six Southern states had already seceded by the time President-elect Abraham Lincoln, on his way to Washington, ceremoniously hoisted the new U.S. flag that included the star of Kansas, our 34th state.

The Civil War in Kansas City

My high school textbook that showed Missouri in blue? Well, consider:

- Across Jackson County, Missouri, only 6 percent of voters chose Lincoln in the 1860 presidential vote. It is not that the region was overrun with proslavery forces – most residents owned no slaves. Yet for businessmen such as Van Horn, Lincoln’s rise and the threat of war chilled hopes that railroads, trade, and westward expansion would favor Kansas City’s prospects. Van Horn’s vote and Missouri’s electoral votes instead went to candidate Stephen A. Douglas, the Illinois Democratic senator who had promoted the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act in hopes of clearing a path for the development of the Transcontinental Railroad.

- A week after cannons fired at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, signaling the start of the Civil War, 200 armed and mounted secessionists seized the federal arsenal at Liberty, just to the northeast of Kansas City in Clay County, Missouri. They occupied the place for a week and stole three or four cannons, between 1,000 and 1,500 muskets, and 419 cavalry sabers. A seemingly incredulous Nathaniel Grant, in charge of the arms depot, wrote to a federal ordnance chief in Washington: “The Union feeling had been so strong in Missouri, and particularly this county, that I had no apprehension that the post would be disturbed.” However, Grant continued, news dispatches from other states “produced much excitement among the people,” which resulted in “secession flags raised in almost every town during the past week.”

- Missouri Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson urged the legislature to join the Confederacy, but his plans were foiled when Union troops captured Jefferson City and other major communities. The state’s secessionist officials fled with armed forces for the southwest part of the state and continued a government in exile, and the Confederacy actually accepted the admission of Missouri and represented the state with an extra star to represent Missouri on its various flags. Other politicians argued that their slaveholding rights would be better protected by remaining in the Union, and for a time they were correct, as President Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation only freed slaves in seceded states, mostly outside of Union control. In addition, runaways to places such as Illinois or the Underground Railroad port of Quindaro, in present-day Kansas City, Kansas, might, after all, be returned.

- Early in the war, at least one Confederate flag shot up in Kansas City. Federal forces from Leavenworth, Kansas moved in at Mayor Van Horn’s request and occupied the town for the war’s duration. Van Horn would oversee a U.S. battalion of Volunteer Reserves from Camp Union at Broadway and 9th Street. On the fort’s grounds, the foundation of developer Kersey Coates’s planned hotel stretched idle until hostilities ceased.

All around Camp Union, “the cannon was constantly repeating the signals of alarm given by the pickets stationed on the outskirts of the city; the heart of every inhabitant quickened by the sound,” wrote the Coates’ daughter, Laura, in her memoirs. She recalled townsfolk gathered to see a rebel “spy” hanged from a scaffold, and how later, spooked children hurried past his grave near a ravine.

The First Baptist Church held together, unlike other congregations in town that split along pro- and antislavery lines. But the First Baptist’s bonds were so fragile that Pastor Jonathan Fuller, a Union man, had to closely monitor the choir’s selection of hymns so as not to offend Southern loyalties.

Near today’s gleaming Sprint Center, the tenuous strands of community ripped apart on August 13, 1863. A makeshift Union prison there collapsed on top of the female Southern-siding kin of Missouri guerrillas. Among the five women who perished was the sister of William T. “Bloody Bill” Anderson. He was one of the so-called bushwhackers, referring to bands of Missourians stalking the countryside for the rebel cause. Southern loyalists believed the jail collapse to be no accident: the Yankees, and Ewing specifically because he happened to own the building, killed those women.

Several days later, hundreds galloped west to Lawrence with Anderson and their guerrilla leader, Quantrill, to eradicate the Union town of its male population. The massacre prompted General Ewing, headquartered in Kansas City, to issue his infamous General Order No. 11, evicting the rural bulk of four Missouri border counties of their entire populations in an ultimately effective but persistently controversial attempt to remove sources of shelter and comfort for the guerrillas. Kansas City and other urban areas were exempted, and some of the refugees were able to move in, provided they swore loyalty to the Union, but the rural areas of Jackson, Cass, Bates, and northern Vernon Counties would long be known as the “Burnt District.”

Border War events would soon serve as an exclamation point to the South’s defeat in the Western theater. In the fall of 1864, armies clashed in a final Confederate campaign to capture Missouri and spoil Lincoln’s reelection. In his “Missouri Expedition,” Major General Sterling Price lost at least 1,000 men in an ill-conceived assault on Pilot Knob, found Union defenses too strong to proceed to St. Louis or Jefferson City, and then in October led his troops west and north to Independence and Kansas City.

At Byram’s Ford over the Big Blue River, and in prior skirmishes at the Little Blue River, Lexington, and Independence, the rebel troops found some traction in pushing back the Union forces under overall command of Major Generals Samuel R. Curtis and James G. Blunt. But then the federals retreated to a rural expanse near present-day Loose Park and virtually surrounded Price’s Army of Missouri.

Imagine a landscape of brush, crops, snaking ravines, and abandoned armaments where some of Kansas City's finest homes now stand.

And this is where the mind’s eye really goes wild. Imagine a landscape of brush, crops, snaking ravines, and abandoned armaments where some of Kansas City’s finest homes now stand. There, at the Battle of Westport, the Union delivered a fatal blow to Price’s army. “What now is the Country Club Plaza was peppered with cannon balls,” a soldier named W.S. Shepherd recalled decades later.

The rebels retreated south and lost again – their supply wagons stuck on the muddy banks of Mine Creek, Kansas. Meanwhile, the Northern states re-elected Lincoln and waited for the American Civil War to grind to an end.

It did end, less than six months after Price’s army backed out of Westport.

Kansas City’s Postwar Miracle

With cannons across the country falling silent, Van Horn’s newspaper declared in April 1865, “we have held on as a community.” But little else about Kansas City’s condition at war’s end was worth celebrating.

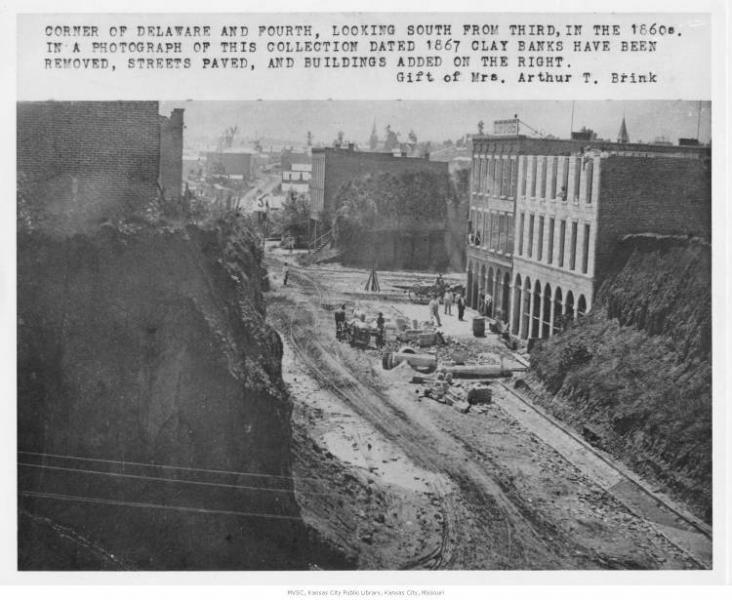

The once starry-eyed City of Kansas staggered out of the conflict star-crossed. Though no official census was taken at mid-decade, contemporary scholars suspect the population was back down to 3,000 – a third less than the tally of 1860. Nearly all of the businesses had changed hands, turned belly up, or were shut down by Union troops.

Publisher and ex-mayor Van Horn headed to Washington, D.C. that year to begin serving the first of three terms as a Republican member of the U.S. House of Representatives. His wife, Adela, stayed back, writing him letters bemoaning the “horrid” state of the town that he was still trumpeting as a future metropolis.

“Mud about a foot deep” outside their home, she wrote, “and no prospect of clearing up.” She later relayed the tragic news of “Doc,” a physician friend shot on his way to a house call. In one especially dreary letter, she told her husband: “This [place] would be a desert to me without your love.”

Civic desperation, a lucky location, and the critical timing of two industries poised for peacetime growth—railroads and meatpacking—would spin Kansas City’s fortunes around within a few fateful years.

Local plans to bridge the Missouri River and hammer down a rail spur going north had collected dust during the fighting, as had other railroad projects around the region.

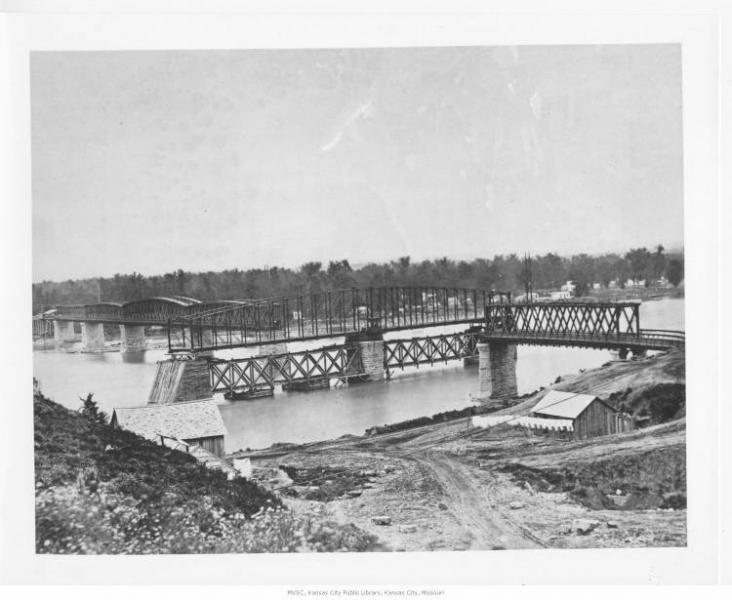

Van Horn emerged the craftiest of boosters. Together with fellow Northerner Kersey Coates and local dealmakers of Southern persuasion, Van Horn was perched in the right place—the United States Congress—when railroad investors in Boston were ready to gamble on Kansas City. In short, our “horrid” town’s elite was happy to set aside dueling wartime passions to make some serious wealth in peacetime. They locked arms and convinced out-of-town railroad interests to finance the Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad Bridge, or simply “Hannibal Bridge.” In 1886 Van Horn sped through Congress the authorizing bill, and Kansas City’s luck soared after its completion in 1869.

The prewar census of 1860: 4,418 people. The 1870 census: 32,260. This count is thought to be inflated, but the sentiment was accurate. By 1890, when cattle carried by rail were butchered in the West Bottoms, some 133,000 people called Kansas City home. Civic leaders who emphasized the “City of the Future,” as they called it, could dismiss as birth pains the horrific beginnings of their budding metropolis. Yet the state line would forever divide.

Books that continue to fly from regional presses have not yet agreed on whose suffering was justified or whose plundering was most crazed. As summed up to me by Grady Atwater of the John Brown Museum in Osawatomie, Kansas: “Both sides were equally monstrous.” He said this inside a cabin where some of Brown’s zealous abolitionists, responsible for a massacre at Pottawatomi Creek and numerous other killings, had met.

The museum that Atwater maintains is mesmerizing and worth a visit – yet my first visit was not made until a quarter of a century after I arrived in Kansas City. I blame that, partly, on my high-school textbooks, which placed Brown at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, but not in Kansas. I also confess to being lackadaisical in challenging the conventions that set the Civil War in the East – not here in the middle of the nation. Today, my advice to anyone who is starting from scratch to understand the passions that culminated in that epic, horrific struggle? Begin by learning what happened in the Kansas City area. It’s as good of a microcosm of the war as any around.

Everyone needs a place to start. And for me, the learning began not out of a fascination for the Civil War or the lawless frontier, and not even out of interest in the history of our divisive state line.

Rather, I was curious about a fellow newspaper man, Van Horn.

“I am again a loser,” he wrote to his parents in 1855 upon leaving for Kansas City from Ohio, where his previous paper collapsed.

Damned if that Yankee didn’t save Kansas City.

Suggested Reading:

The Kansas City Star. "Civil War! Inside the Conflict that Forever Divided Kansas and Missouri." 2011.

Miller, Patricia Cleary. Westport, Missouri's Port of Many Returns. Kansas City, MO: Lowell Press, 1983.

Montgomery, Rick and Shirl Kasper. Kansas City: An American Story. Kansas City, MO: Kansas City Star Books, 1999.

Neely, Jeremy. The Border Between Them: Violence and Reconciliation on the Kansas-Missouri Line. Columbia London: University of Missouri Press, 2007.

Cite This Page:

Montgomery, Rick. "Foreword on the Civil War in Kansas City" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Friday, April 26, 2024 - 19:33 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/essay/foreword-civil-war-kansas-city

Rights/Licensing:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License