By Terry Beckenbaugh, U. S. Air Force Command and Staff College

Event Summary:

- Date: September 18-20, 1861, with skirmishing starting September 12

- Location: Lexington, Missouri

- Adversaries: pro-Confederate Missouri State Guard Maj. Gen. Sterling Price and deposed Missouri Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson vs. Union Col. James A. Mulligan and Maj. Robert T. Van Horn

- Size of Forces: 15,000 to 20,000 in the Missouri State Guard (MSG) vs. approx. 3,500 Union soldiers

- Casualties: Approx. 100 from the MSG vs. 1,774 Union soldiers killed, captured, wounded, or missing

- Result: MSG victory, $900,000 confiscated by the victors

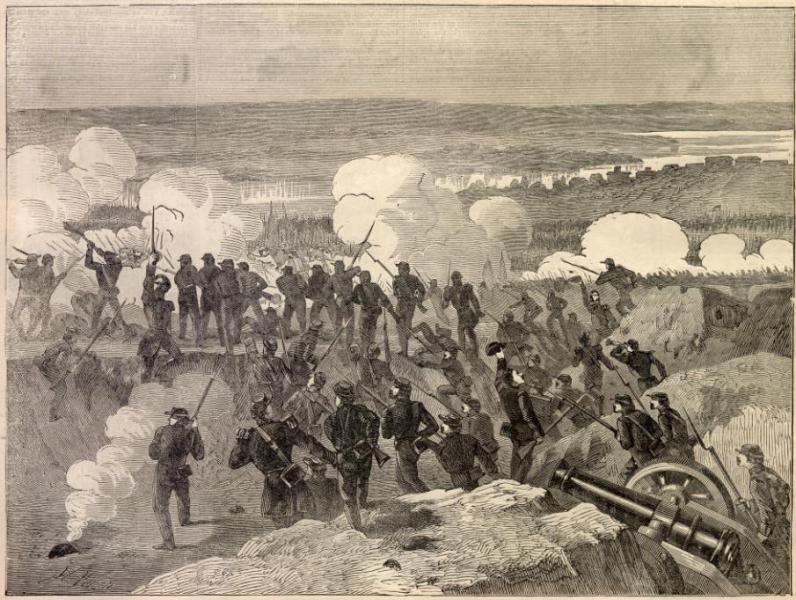

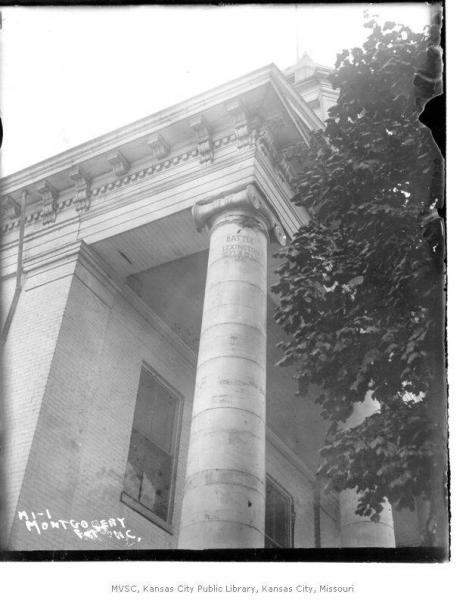

The Battle of Lexington, Missouri, fought on September 18-20, 1861, was a victory for the Missouri State Guard (MSG) in the early stages of the Civil War. In the short term, the victory boosted the spirits of Missouri secessionists, but the State Guard failed to leverage any long-term gains from the “Battle of the Hemp Bales,” so called because the MSG used hemp bales to encircle the federal position at Lexington.

A combined Confederate and MSG force, commanded by Brigadier General Benjamin McCulloch and Major General Sterling Price, respectively, had defeated a smaller Union force at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek on August 10, just outside of Springfield. The federals retreated toward Rolla, abandoning central Missouri, but Price and McCulloch could not agree on a subsequent plan of action. Price wanted to move to Lexington, located in the heart of the “Little Dixie” region and thus friendly to the State Guard, and bring in recruits from north of the Missouri River.

McCulloch believed the State Guard was little more than an armed mob and should focus instead on Missouri's official secession.

McCulloch believed the State Guard was little more than an armed mob and should focus instead on Missouri’s official secession so it could receive arms, training, and equipment from the Confederacy. Furthermore, McCulloch argued, his orders stated he was to protect Arkansas and the Indian Territory from Union invasion, not invade Missouri – still a part of the United States. McCulloch only aided the MSG at Wilson’s Creek because, in his superiors’ view, a foreign country, Missouri, formally requested the Confederacy’s aid against outside aggression (the U.S.).

Already on shaky legal ground due to the fact that Missouri had not seceded, and with no imminent federal threat, McCulloch saw no legal reason to aid the State Guard in its attack on Lexington—especially since in the immediate aftermath of Wilson’s Creek the only troops in Lexington were Missouri-raised federal troops. If Missouri formally seceded and joined the Confederacy, the legal wrangling would be a moot point. Finally, McCulloch believed that the MSG would gain new recruits, but it could not equip, train, and feed them, thus capturing Lexington would yield little benefit to the State Guard.

Missouri’s pro-secession Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson had another reason to go to Lexington: money. The federals confiscated over $900,000 from the Lexington Bank to forestall the secessionist government’s acquisition of the funds. Jackson argued that the U.S. confiscation was illegal. Additionally, the pro-secession Missouri State Legislature passed a bill that gave local banks relief, if they in turn loaned the state a portion of their holdings. This “loan” amounted to $37,000, and Jackson meant to collect that money and deny the federals the rest of the $900,000. Jackson’s arguments, along with Price’s natural inclination to reach for military glory, decided the matter in favor of moving on Lexington.

Price knew that Lexington was not strongly held by federal forces. Union Colonel James A. Mulligan moved his 23rd Illinois Volunteer Infantry into Lexington on September 8, finding the 1st Illinois Cavalry and approximately 350 Missouri Home Guards already in and around the town. Two companies of Major Robert T. Van Horn’s Missouri Battalion trickled in before Colonel Everett Peabody’s 13th Missouri made it to Lexington, just ahead of Price and the 15,000 strong MSG on September 11. That gave Mulligan, the ranking U.S. officer, roughly 3,500 men, seven six-pound cannons, and two mortars. He realized he needed more of everything, so he started the men digging extensive fortifications on September 11, on and around College Hill, home of the Masonic College, which became Mulligan’s headquarters.

The MSG arrived on September 12 and skirmished inconclusively with the federals. Price decided to try one attack on Mulligan’s fortifications, which failed and convinced Price his men needed rest and more ammunition. With few supplies close by, Price had the men bivouac south of town on the Lexington fairgrounds to await supply, ammunition trains, and reinforcements. Both sides held councils of war on the night of the 12th. The federal commanders voted to abandon Lexington, but Mulligan overruled them. The MSG leaders voted to surround the federals, but not to attack. By September 18, Price received ammunition and reinforcements, bringing the State Guard’s strength to between 15,000 to 20,000 men. Price waited no more.

The MSG began its attempt to evict the federals from Lexington in earnest on the morning of the 18th. The State Guard opened an artillery bombardment on the federal position atop College Hill at 9 a.m., and Price ordered his men to capture the Anderson House, a prominent three-story, brick structure that lay just outside of Union lines. The federals used the house as a hospital and marked it as such. Since no armed men were in the house, the MSG easily took it and used it as a platform for harassing small-arms fire. This infuriated Mulligan, who believed the State Guard violated the rules of war in attacking a hospital, and he sent Company B of the 23rd Illinois to recapture the house. The MSG men who occupied the house were quickly routed, but the 23rd Illinois soldiers executed three of the captured State Guard forces. Price decried this as an “act of savage barbarity.”

It was during this struggle over the Anderson House that bugler George Henry Palmer, of Company G, 1st Illinois Cavalry, won a Medal of Honor. Palmer volunteered to lead the assault party despite not being a member of the 23rd Illinois. Eventually Price ordered the Anderson House re-taken, and later in the day the MSG attacked with overwhelming force and evicted the federals for good.

With their lone water source cut off, the only chance the federals had of keeping Lexington was if the State Guard encirclement was broken.

The MSG moved to consolidate its position and tighten the noose around the Unionists. After capturing the Anderson House, State Guard Colonel Ben Rives sent his men to the Missouri River to capture a steam boat and ferry, both loaded with supplies. In doing so, they also cut the federals off from the closest spring to their lines—and in the process denied the federals any water sources. This proved to be crucial to the outcome of the battle, as the federals had strong fortifications, superior weaponry (many of the MSG were armed with their own hunting rifles and shotguns) and food. But they could not go long without water.

With their lone water source cut off, the only chance the federals had of keeping Lexington was if the State Guard encirclement was broken. Major General John C. Frémont, who commanded the Union Department of the West, which included Missouri, ordered three different detachments from various parts of Missouri and Kansas to relieve the Lexington garrison. None of their efforts were strong enough to break through and lift the State Guard’s encirclement. With no water and no reinforcements, it was only a matter of time.

The federals dug two wells within their defensive perimeter in a desperate search for water. Both came up dry. On the evening of the 19th, MSG Brigadier General Thomas Harris, or someone in his 2nd division, originated the idea of using hemp bales as a moving fortification. Soaked in water, the hemp bales were very heavy, but they were also fireproof and impervious to cannon and small arms fire. Other division commanders quickly adopted the idea, and soon a hemp ring surrounded the federal position atop College Hill. The ring gradually tightened, and the Unionists were powerless to stop the MSG’s advance. The situation looked bleak for the federals as the sun went down on September 19th.

When Price asked Mulligan if he was willing to surrender, the flustered federal commander stated that he thought Price was surrendering.

The State Guard decided to attempt one more assault upon the federal fortifications the following day. Harris’s men, who were the closest to the Unionists, stormed the trenches—and were thrown back. After repulsing the MSG attack, a white flag appeared on the fortifications. There was confusion about who put it up, as Mulligan did not. When Price asked Mulligan if he was willing to surrender, the flustered federal commander stated that he thought Price was surrendering. When the confusion was sorted out, it was Major Frederick Becker of the Missouri Home Guards (U.S.) who put up the white flag. Mulligan called an impromptu council of war, and by a vote of 6-2, his subordinate officers voted to surrender (Mulligan voted not to surrender). Realizing his hopeless situation, Mulligan reluctantly agreed to immediate unconditional surrender.

With the victory, the MSG gained badly needed ammunition and supplies, not to mention the $900,000 confiscated from the Lexington Bank. But in the end, McCulloch had been right, as Price could not feed and equip the many men who joined during the engagement at Lexington. The State Guard moved back into the southwest corner of the state, and that’s where it was when the federal Army of the Southwest began the Pea Ridge campaign in January 1862.

Suggested Reading:

Castel, Albert E. General Sterling Price and the Civil War in the West. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1968.

Gerteis, Louis. The Civil War in Missouri: A Military History. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2012.

Gillespie, Michael. The Civil War Battle of Lexington, Missouri: A Concise History of the Siege and Battle September 12-20, 1861 Based on Eyewitness Accounts, 2nd edition. Lone Jack: Michael Gillespie, 2007.

Patrick, Jeff. "The Battle of Lexington," North & South Magazine, vol. 1, no. 3 (February 1998), 52-67.

Shalhope, Robert E. Sterling Price, Portrait of a Southerner. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1971.

Cite This Page:

Beckenbaugh, Terry. "First Battle of Lexington (or "Battle of the Hemp Bales")" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Thursday, April 25, 2024 - 18:24 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/first-battle-lexingt...