By Jeremy Prichard, University of Kansas

The “Bogus Legislature” refers to Kansas Territory’s first governing body, established in 1855. Free-Soil and antislavery supporters in the area provided the moniker after widespread accounts of fraudulent voting in the March 30, 1855, election that selected the assembly’s initial members. The nickname stuck, and the partisan rift surrounding the two-year legislative session played a prominent role in the early years of Bleeding Kansas.

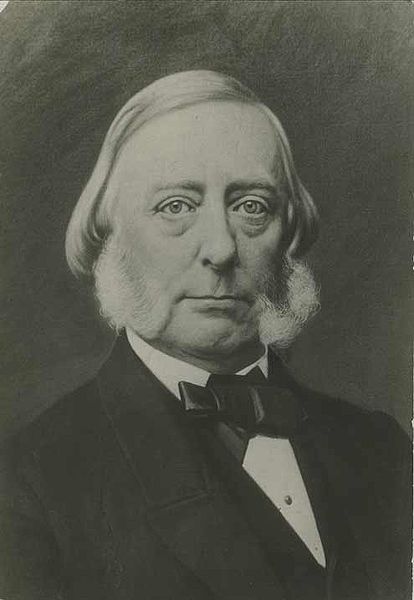

Members elected to this first legislature were expected to determine whether Kansas would enter the Union as a free or slave state. Slaveholding and proslavery Missourians, led by former U.S. Senator David R. Atchison, already worried about the fate of their own state’s institution due to sharing a border with two states that prohibited slavery: Illinois and Iowa. In order to protect slavery within its own borders, these Missourians wanted to prevent Kansas from becoming a third free state on their western edge that might provide a safe haven for runaway slaves.

The situation produced arguably some of the most notorious forms of fraudulent voting in 19th-century America. Missouri voters challenged the authority of election judges throughout the territory by threatening them (with death in some instances) for refusing to accept their ballots. The border ruffians, as violent proslavery Missourians became known, also threatened antislavery voters at election sites, convincing many Free-Soilers to stay home that day.

Proslavery supporters stuffed so many ballots that the number of votes cast in Leavenworth was five times the size of the town’s population.

Proslavery supporters stuffed so many ballots that the number of votes cast in Leavenworth was five times the size of the town’s population, and throughout Kansas twice as many ballots were cast as there were registered voters. Approximately 90 percent of the vote went to proslavery candidates, many with permanent residency in Missouri. Free-Soil Kansans began referring to the incoming governing body as the “Bogus Legislature” before officials even finished tallying the votes.

Missourians who crossed the border to vote in Kansas claimed they had fulfilled residency requirements merely with their physical presence in the territory on election day. They ignored the governor’s proclamation authorizing only residents of the territory to vote. Many Missourians argued that their actions were no worse than the New England Emigrant Aid Company and other organizations that encouraged voters from Northern states to settle and vote in Kansas’s elections.

Andrew Reeder, a Democrat installed by President Franklin Pierce as the territory’s first governor, tried with little success to enforce lawful elections in the territory. He ordered a special election for those regions that experienced indisputable illegal voting in the March election. When the overwhelmingly proslavery legislature opened the session, however, the leadership ousted those who won seats in the special election and reinstituted those chosen in the controversial first election. Shortly afterward, Free-Soil candidates elected to the legislature gave up their seats, claiming they could not acknowledge the legitimacy of the proslavery government since it failed to represent the views of a majority of residents in the territory.

The proslavery legislature’s main objectives were to sanction and promote slavery in Kansas. One of its first acts was transferring the capitol from Pawnee in central Kansas to Lecompton, a location closer to the Missouri border. The body also passed laws that severely punished anyone who criticized or posed obstacles to the institution’s existence in the territory.

Opponents dismissed the legislature’s legitimacy and established their own territorial government in Topeka. This move intensified the tensions within Kansas, but it also reverberated beyond its borders. National Democrats and Republicans chose which legislature to acknowledge according to their respective sympathies.

The discord created by the territory's first government played a significant role in Bleeding Kansas and contributed to the growing national crisis.

In 1857, one of the Lecompton legislature’s last actions was establishing a convention to write a state constitution. Free-Soil voters again refused to participate in the election of the convention’s members; therefore, proslavery candidates made up a majority of the body. Members drafted a document, known as the Lecompton Constitution, which reflected their pro-Southern sentiments and that favored slavery’s existence—in some version—in the future state. Before voters had a chance to accept or reject the proposed constitution, Kansans in the territory (most of whom were now against slavery’s implementation in the state) elected a Free-State majority to the new legislature set to convene in 1858. On January 4, 1858, residents handily repudiated the Lecompton Constitution.

The actions of the so-called “Bogus Legislature” politicized Kansans, including many who otherwise had little interest in political matters. The discord created by the territory’s first government played a significant role in Bleeding Kansas and contributed to the growing national crisis. Even though Free-State candidates won a majority of seats in the next session that opened in 1858, Kansas did not become a state until January 1861.

Suggested Reading:

Etcheson, Nicole. Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004.

McPherson, James. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Cite This Page:

Prichard, Jeremy. "Bogus Legislature" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Friday, April 19, 2024 - 06:19 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/bogus-legislature