By Matthew E. Stanley, Albany State University

The Free-State Party was an antislavery political coalition that was organized in territorial Kansas in 1855 to oppose proslavery Democrats. From 1855 to 1859, party members thwarted the expansion of slavery into Kansas Territory by forcibly resisting proslavery forces on the ground and drafting antislavery legislation in conjunction with the national Republican Party.

By 1854 the national debates over whether to allow slavery in the territories acquired from the Mexican-American War had reached a fever pitch. The Kansas-Nebraska Act, passed on May 30, 1854, was a piece of watershed legislation in American history. Drafted by Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas and containing the provision of “popular sovereignty,” it created two new territories and enabled settlers and their legislatures to determine whether the future states would be slave or free. Congress had previously applied popular sovereignty in the New Mexico and Utah Territories under the Compromise of 1850, and due largely to a climate unsuitable for plantation slavery, little controversy ensued. The Kansas-Nebraska Act, on the other hand, allowed the possibility of slavery on large tracts of land that had been legally designated for free territories by the Missouri Compromise of 1820, and it planted the seeds of political violence over slavery in the West.

On March 30, 1855, Kansans elected a territorial legislature, deciding in effect whether the future of Kansas would be slave or free.

Seeking to establish Kansas as a state without slavery, antislavery settlers from Massachusetts, upstate New York, Ohio’s Western Reserve, and Iowa became known as “Free-Soilers.” Some of these settlers were abolitionists, while others simply hoped to preserve an all-white society of yeoman farmers in the West, without slavery (thus limiting direct economic competition with slaveholders). On March 30, 1855, Kansans elected a territorial legislature, deciding in effect whether the future of Kansas would be slave or free. Several thousand proslavery “border ruffians” from western Missouri flooded over the border, stuffing ballot boxes in a resounding victory for proslavery voters. The Free-Soilers referred to the resulting territorial government as the “Bogus Legislature,” but in spite of the election fraud, Democratic President Franklin Pierce continued to approve of the proslavery legislature and denounced the Free-Soilers as insurrectionists.

In response, Free-Soilers held a convention at Big Springs in July 1855, laying out their case against voter fraud in the March 1855 elections. Underscoring the initial moderation of most Free-Soilers, they held the convention at Big Springs rather than Lawrence, which had a reputation for abolitionist radicalism.

The antislavery settlers were deeply divided over race. Tensions persisted between morally-inclined abolitionists and antislavery settlers who cared little about black freedom but did not wish to compete with black labor in Kansas. Indeed, antislavery settlers divided over whether to reject the territorial government, to boycott territorial elections altogether, or to use violence to achieve political aims. Moreover, abolitionist Easterners consistently broke with conservative Westerners who opposed black emigration and suffrage.

Amid the infighting, this aggrieved coalition of antislavery settlers formally formed the Free-State Party on September 5, 1855.

Amid the infighting, this aggrieved coalition of antislavery settlers formally formed the Free–State Party on September 5, 1855. The first order of business was to form a separate territorial legislature at Topeka and draft an antislavery constitution. Again, factionalism arose between abolitionist New Englanders led by Charles L. Robinson and more conservative Midwesterners associated with James H. Lane, a U.S. congressman from Indiana who supported black exclusion from the territory.

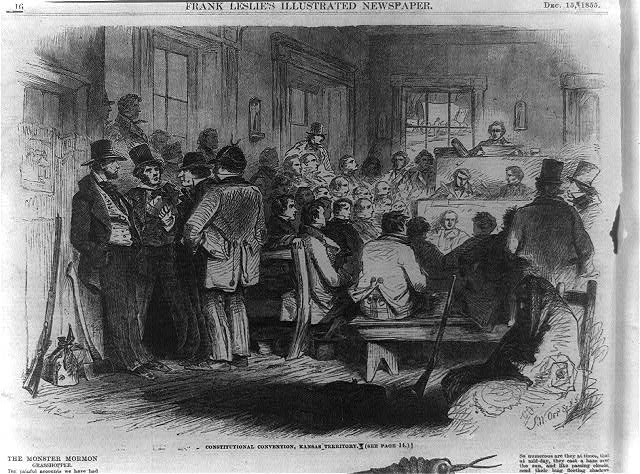

Despite the internal divisions, Free-State Party members held a constitutional convention at Topeka in October 1855, drafted and passed their own constitution. The resulting “Topeka Constitution” outlawed both slavery and the settlement of free African Americans in Kansas, and the constitution passed in a territory-wide referendum on December 15, 1855, as proslavery men boycotted the vote on legislation drafted by what they saw as an illegitimate legislature. However, the Topeka Constitution stalled in the U.S. Senate, as support for it was largely confined to the North. Whereas congressional Republicans supported the Free-Staters, national proslavery leaders advocated the Lecompton Constitution, a rival proslavery document championed by the “Bogus Legislature” starting in September 1857.

Like its proslavery opposition, the Free-State Party used paramilitary groups to buttress its politics at the ground level. Extralegal militia outfits such as the “Kansas Legion” operated in conjunction with some Free-Soil politicians. Bloodshed erupted between proslavery “bushwhackers” and Eastern-backed anti-slavery “jayhawkers,” as a series of violent episodes beginning with the proslavery raid on Lawrence in May 1856 led to the period known as “Bleeding Kansas.”

Against a violent and ever more radicalized backdrop, and as the political crisis heightened and new antislavery settlers poured into Kansas, abolitionists gradually gained preeminence in the Free-State Party.

Against a violent and ever more radicalized backdrop, and as the political crisis heightened and new antislavery settlers poured into Kansas, abolitionists gradually gained preeminence in the Free-State Party. The political transformation of Lane—described by historian Nicole Etcheson as a “chameleon-like change”—from conservative pro-“Bogus Legislature” Democrat to opponent of that legislature (and eventually an abolitionist jayhawker himself) underscored the rapid growth of the Free-Soil movement and its abolitionist elements in Kansas.

Free-Staters abandoned the conservative Topeka Constitution and opted to participate in the October 1857 elections, resulting in the more radically abolitionist Leavenworth Constitution. Drafted and adopted in the spring of 1858, the Leavenworth Constitution made no distinction between black and white men and even included a referendum on black suffrage. However, the U.S. Senate never ratified it.

The territorial legislature passed into Free-State hands in the fall of 1858, and voters resoundingly overturned the Lecompton legislature in favor of the new antislavery Wyandotte Constitution in October 1859. Although the Wyandotte Constitution did not go so far as the Leavenworth Constitution in granting rights to African Americans (there was no provision for black suffrage), it did appear certain that Kansas would eventually enter the Union as a free state. Moreover, the growing regional opposition to slavery in Kansas drew many Northern Democrats into the fledgling Republican Party.

The Free-State Party formally merged with the national Republican Party in 1859 at a meeting in Osawatomie, which was attended by the editor of the New York Tribune and famed abolitionist reformer, Horace Greeley. Some Free-Staters became nationally prominent Republicans. James Lane, for instance, eventually became one of the first two senators from Kansas as a Republican and served as a Union general during the Civil War. The U.S. Senate ratified the Wyandotte Constitution and Kansas was admitted to the Union as a free state in January 1861, but by then the Civil War was just beginning and Kansans would have to endure another four years of turmoil.

Suggested Reading:

Etcheson, Nicole. Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004.

Rawley, James A. Race & Politics: "Bleeding Kansas" and the Coming of the Civil War. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1969.

SenGupta, Gunja. For God and Mammon: Evangelicals and Entrepreneurs, Masters and Slaves in Territorial Kansas, 1854-1860. Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 1996.

Cite This Page:

Stanley, Matthew. "Free-State Party" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Saturday, April 27, 2024 - 06:50 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/free-state-party