By Zach Garrison, University of Cincinnati

Law Summary:

- Date signed into law: May 30, 1854

- Chief proponent: U.S. Senator Stephen A. Douglas, of Illinois

- Signed into law by: President Franklin Pierce

- Results: recognition of Kansas and Nebraska as organized U.S. territories; popular sovereignty; expansion of the Republican Party; "Bleeding Kansas;" the American Civil War

In 1854, amid sectional tension over the future of slavery in the Western territories, Senator Stephen A. Douglas proposed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which he believed would serve as a final compromise measure. Through the invocation of popular sovereignty, Douglas’s proposal would allow the citizens of the Kansas and Nebraska Territories, rather than the federal government, to decide whether to permit or prohibit slavery within their borders.

In response to the Kansas-Nebraska Act, pro- and antislavery forces descended on Kansas, followed by an outburst of violence and intimidation.

In response to the Kansas-Nebraska Act, pro- and antislavery forces descended on Kansas, followed by an outburst of violence and intimidation. Dissent in the North and West was so profound that the antislavery Republican Party formed even before the law’s enactment and quickly peeled Northern, antislavery members away from the Democratic, Whig, and Free-Soil Parties, with the latter two parties formally dissolving by the end of 1854 and 1860, respectively.

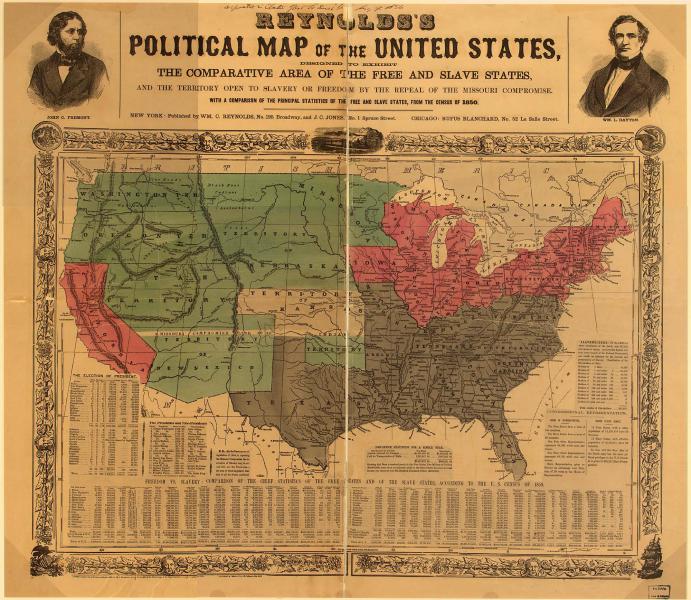

During the 1840s, the push to organize the Kansas and Nebraska Territories was inspired by the prospects of a Transcontinental Railroad and Western settlement. The problem of determining the railway’s route—whether it would pass through northern (free) or southern (slave) territory—was hotly debated and prevented any construction. For proslavery politicians such as Missouri Senator David Rice Atchison, the primary deterrent to a Northern route was the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which banned slavery north of Missouri’s southern border at the 36°30' parallel.

Without the support of slave-state Senators, the likelihood of completing the railroad remained very low. Hoping to bridge the divide, Stephen Douglas stepped in and argued that the rule of popular sovereignty that had effectively been implemented in the Compromise of 1850 in the Utah and New Mexico Territories should also apply to Kansas and Nebraska. Douglas also had personal and financial reasons for securing a Northern route, which he believed would run through his home state of Illinois and more specifically through the city of Chicago, where he had heavily invested in real estate. In an effort to further appease Southern politicians and win their votes, Douglas worked behind the scenes to ensure that the Missouri Compromise line was formally repealed.

Opponents of the law expressed outrage over the dismissal of the Missouri Compromise and accused Douglas of submitting to the slave power. “Anti-Nebraska” organizations quickly materialized throughout the North and Midwest as the cause of free soil united disparate groups around the central premise of preventing the western expansion of slavery.

Seeking to leverage the principles of Popular Sovereignty, immigration aid societies in both the North and South encouraged settlement in Kansas, where two opposing territorial governments and constitutions formed as a localized civil war exploded. Military-minded combatants included so-called “border ruffians,” proslavery Missourians who felt deeply threatened by the possibility of a Free-State on their Western border, in addition to Iowa to the north and Illinois to the East. Border ruffians fought bitterly with Free-State “jayhawkers” and both carried out violent raids and committed massive voter-fraud, leading to national headlines describing “Bleeding Kansas” as the epicenter of America’s sectional divide.

The fiery abolitionist John Brown arrived in Kansas in 1855, bringing with him an interpretation of the Kansas-Nebraska Act as a divine call to arms.

The fiery abolitionist John Brown arrived in Kansas in 1855, bringing with him an interpretation of the Kansas-Nebraska Act as a divine call to arms, and his acts of aggression against Missouri slave owners came to characterize the violence along the border. By 1856, political antagonisms over the Kansas-Nebraska Act only intensified in the halls of Congress, culminating in the caning of Senator Charles Sumner by Preston Brooks, a Congressman from South Carolina. Instead of denouncing Brooks’s violent actions, which might have eased the national divide, inspired Southerners sent Brooks hundreds of canes as a sign of solidarity.

Another consequence of the Kansas-Nebraska Act was the usurpation of longstanding party affiliations according to sectional loyalties. The cause of free soil over the interest of slavery led many Northern, antislavery Whigs, Free-Soilers, and Democrats to abandon their traditional party affiliations and join the new Republican Party in 1854. In the 1856 election, the Republicans produced their first presidential candidate, John C. Frémont, who represented solely Northern interests. Despite a losing campaign, Frémont managed to win over a substantial number of voters.

Combined with the admittance of Kansas into the Union as a free state in January 1861, the election of Republican Abraham Lincoln in 1860 represented a major defeat for Stephen Douglas and the hope that popular sovereignty would prevent a complete breakdown of national politics along sectional lines. In a bitter ironic twist, rather than achieving a lasting compromise, the Kansas-Nebraska Act ultimately divided the nation and led it further down the path to civil war.

Suggested Reading:

Etcheson, Nicole. Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004.

Potter, David. The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861. New York: Harper & Row, 1976.

Cite This Page:

Garrison, Zach. "Kansas-Nebraska Act" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Saturday, April 27, 2024 - 06:44 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/kansas-nebraska-act