By Jonathan Earle, Louisiana State University

In many respects, Kansas—and the question of whether slavery, legal in neighboring Missouri, would be allowed to spread to the territory—was the central issue of the 1860 presidential election, the most significant in U.S. history. Curtailing slavery’s expansion and admitting Kansas as a free state was a key plank in the Republican Party’s platform that year, just as it was during the party’s first presidential election in 1856. The seemingly unanswerable “Kansas Question” and the issue of slavery’s expansion split the venerable Democratic Party into Northern and Southern factions, allowing the Republican Abraham Lincoln to win the election without a single Southern electoral vote.

The election of a Republican president, on a platform promising a halt to slavery’s expansion at the Missouri-Kansas border, was a turning point not just for the region, but for the entire United States. National political events between “Old Osawatomie” John Brown’s 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry and the commencement of the Civil War in April 1861 unveiled the centrality of Kansas in the larger contest.

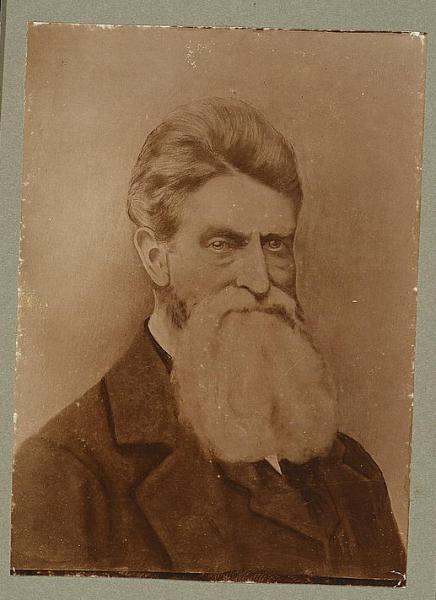

“Osawatomie John Brown” and the Raid on Harpers Ferry

When the abolitionist John Brown arrived in Kansas Territory in 1855, he joined a growing band of settlers from the North who hoped to keep slavery and slaveholders out. Yet unlike most antislavery partisans, who wielded words, petitions, and moral suasion to attack the South’s “peculiar institution,” Brown arrived with weapons and a willingness to use violence to keep Kansas free. Before Brown’s appearance on the scene, proslavery settlers and neighboring Missourians made successful use of intimidation and fraud to win territorial elections.

For the next four years, Brown worked to make the territory “bleed” with deadly attacks on proslavery settlers at Pottawatomie Creek and in clashes with armed militiamen and their deputies at the battles of Black Jack and Osawatomie. He left the territory in early 1859, intending to take his war against slavery into Virginia, where he planned to incite a slave rebellion in the Appalachian Mountains.

Several of Brown’s comrades in his raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry had ridden with him in Kansas, and it was under the guise of carrying out additional violence in Kansas that Brown raised funds from New Englanders for the raid. While the raid itself turned out to be an unmitigated disaster, Brown’s foray into Virginia had far-reaching political implications for the entire nation – already in the midst of the 1860 presidential campaign.

As historian Nicole Etcheson writes in her essay on this website, “Northerners were reminded of the horrors of a slave system that provoked men to such drastic violence. Southerners insisted that there was no difference between violent abolitionists such as John Brown and Republican candidates such as Abraham Lincoln. Americans noted how Brown’s experience in Kansas had driven him to this attack.”

Harpers Ferry’s Impact on the 1860 Election

Political pundits gave Abraham Lincoln, a practicing lawyer and Illinois politician who had not held a political office since 1849, very little attention at all.

Largely as a result of “Bleeding Kansas” (and its mismanagement by Democratic Presidents), the brand-new Republican Party had a very real shot at capturing the main prize in the 1860 election, in just its sixth year of existence. But who would that Republican nominee be? Senator William Seward of New York, author of the famed “Higher Law” speech, was the clear front-runner, followed by Ohio Governor Salmon Chase and St. Louis lawyer Edward Bates. Political pundits gave Abraham Lincoln, a practicing lawyer and Illinois politician who had not held a political office since 1849, very little attention at all – despite his reputation-making debates with Democratic rival Stephen Douglas in a campaign for the United States Senate in 1858. If anything, Lincoln was mentioned as “vice-president material.”

But all political bets were off the moment John Brown unleashed the potentially untamable forces of slave insurrection and disunion onto an already fragile scene. Heretofore moderate Southerners demonized even tepid antislavery Northerners as potential John Browns, and a surprising number of Northerners described Brown’s actions in hagiographic terms. Leading Northern intellectual Ralph Waldo Emerson, for example, said that once Brown was executed, he would make the “gallows glorious like the cross.”

It may not have been entirely fair, but the frontrunner, William Seward, became the “face” of Republican defenders of John Brown, mostly because of a reputation for radicalism due to his famous “Higher Law” speech. For example, the journalist James Shepherd Pike recalled that he “had a very strong belief in Mr. Seward[’]s nomination till since Mr. Brown visited Virginia. That little incident has thrown a new cloud over the presidential talk and I think obscured Mr. Seward[’]s prospects not a little.”

The biggest beneficiary of Brown’s raid turned out to be the lesser-known candidate, Abraham Lincoln, who as a westerner widely viewed as a “moderate” on the slavery issue, made Seward look more radical than he was. In order to press his advantage against his Republican rivals, Lincoln accepted an invitation from a distant relative to visit Kansas Territory, which was “ground zero” of the slavery debate and the place where Brown made his reputation. “The Harpers Ferry affair doubtless to some Extent hurt us in New York,” Mark Delahay wrote to Lincoln, his personal friend. But this was actually good news for Lincoln, “as an old line Clay Whig (born in Kentucky)” who thus didn’t have to worry about being branded—at least not in 1859—as a Brown sympathizer.

Abraham Lincoln’s Trip to Kansas, December 1859

Lincoln was in Leavenworth, Kansas Territory, when he heard the news of John Brown’s execution.

A trip to Kansas Territory in December 1859, Lincoln reasoned, would allow him to travel to the center of the nation’s continuing political storm, ingratiate himself with Kansas Republicans by helping with an upcoming local election, and rough out new ideas for the bigger speech he had agreed to deliver at the New York’s Cooper Union in February 1860. Lincoln was in Leavenworth, Kansas Territory, when he heard the news of John Brown’s execution in Charles Town, Virginia, and he immediately invoked a tone that mixed condemnation of Brown’s actions with notable support for his ideals. “John Brown has shown great courage [and] rare unselfishness, as even [Virginia] Governor Wise testifies. But no man, North or South, can approve of violence and crime.”

When he heard about Brown’s death while speaking in Leavenworth, Lincoln announced, “Old John Brown has just been executed for treason against a state. We cannot object, even though he agreed with us in thinking slavery wrong. That cannot excuse violence, bloodshed, and treason.” He went on to look clearly ahead to the coming canvass and warned secessionists: “So, if constitutionally we elect a [Republican] President, and therefore you undertake to destroy the Union, it will be our duty to deal with you as old John Brown has been dealt with. We shall try to do our duty. We hope and believe that in no section will a majority so act as to render such extreme measures necessary.”

View Lincoln's Visit to Kansas in a larger map

Two days later, still in Leavenworth, Lincoln spoke even more politically, calling any attempt “to identify the Republican party with the John Brown business” an “electioneering dodge.” A reporter noted that in “Brown’s hatred of slavery [Lincoln] sympathized with him. But Brown’s insurrectionary attempt he emphatically denounced. He believed the old man insane, and had yet to find the first Republican who endorsed the proposed insurrection.”

Republicans didn’t cause slave insurrections, Lincoln exclaimed for the first time in public – slavery did. He added that even the staunchest Fire-Eater (a secessionist Southerner) couldn’t fairly blame the Nat Turner slave rebellion of 1831 on the Republican Party. Henry Villard, no fan of Lincoln’s to that point, called the Leavenworth speech “The greatest address ever heard here.” Lincoln took his notes and reactions from his Kansas trip home to Illinois, where he pored over old law books and historical documents, resulting in the speech he delivered at the Cooper Union in New York City. The address catapulted his campaign onto the national political stage.

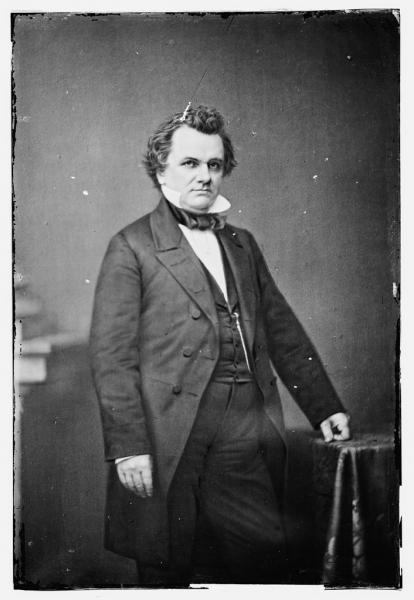

Stephen Douglas, the Democrats, and the Kansas Question

The other national figure damaged by John Brown’s raid and the further sectional polarization that followed in its wake was Lincoln’s longtime rival from Illinois, Senator Stephen Douglas. Brown’s assault on the South further emboldened disunionists in the region and drove a wedge between these Fire-Eaters and Douglas, the presumed Democratic front-runner.

Douglas, the original author of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, had long harbored presidential aspirations. He fell short in 1856, succumbing at the Democratic convention to the eventual winner, James Buchanan of Pennsylvania. The next three years were full of frustration for Douglas, who had proposed that the new law’s “popular sovereignty” provision (allowing the settlers in a territory to decide for themselves whether slavery would be legal or not) would democratically heal divisions in Kansas. One of the central conflicts between Douglas and the Southern wing of his party (a wing that would be essential to winning the nomination in 1860) was Kansas’s proslavery “Lecompton Constitution.”

In 1857, three years after Douglas’s Kansas-Nebraska Act became law, the territorial legislature—which was overwhelmingly proslavery since Senator David Rice Atchison led 5,000 Missourians into Kansas to stuff ballot boxes and suppress the Free-State vote in 1855—convened to craft a state constitution, dubbed the “Lecompton Constitution.” The new compact explicitly enshrined slavery in the proposed state and protected slaveholders’ rights, despite the growing majority of bona fide antislavery settlers in Kansas, many of whom had boycotted the referendum on the new constitution. Far from popular sovereignty, it was a glaring example of a constitution not matching the political outlook of the people it was supposed to represent.

President Buchanan, though a Northerner, remained a strong supporter of slavery and slaveholder’s rights, and he endorsed the Lecompton Constitution; but many other northern Democrats, led by Douglas, sided with the Republicans in opposition to the glaringly proslavery document. Though defeated twice—once by territorial voters in Kansas and again in the U.S. House of Representatives—the Lecompton Constitution widened the gap between the Northern and Southern wings of the once-solid Democratic Party.

Douglas’s best arguments for himself as a Democratic standard-bearer in 1860 were his so-called moderation on the slavery issue and his political viability in each section of the country. None of his rivals could boast a similar national appeal, but his political opponents in the Deep South and within the Buchanan administration did everything they could to weaken his candidacy. Ever since his introduction of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, Douglas had advanced the doctrine of popular sovereignty, but the Supreme Court ruled in the 1857 Dred Scott v. Sandford case that the Constitution protected slavery in all the territories.

If need be, the Fire-Eaters were willing to rend the nation over the issue of protecting slavery in all the territories.

Then, during his 1858 debates with Abraham Lincoln, Douglas only narrowly ensured his reelection to the U.S. Senate by adopting the Freeport Doctrine, which looked to many Southerners like a way to nullify Dred Scott. Increasingly, Southern Fire-Eaters began to profess a willingness to tear the party asunder and to stop a Douglas candidacy in its tracks at the Democrats’ nominating convention, set for Charleston. And, if need be, the Fire-Eaters were willing to rend the nation over the issue of protecting slavery in all the territories.

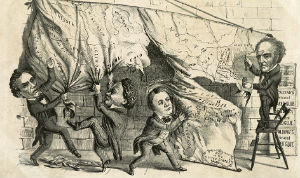

The Democratic Party Splits in Charleston

On April 23, 1860, Democrats convened in what was probably the worst possible place for a Douglas coronation: Charleston, South Carolina, easily the most proslavery city in the entire country.

The Fire-Eaters packing the hall demanded the adoption of an explicitly proslavery platform that would endorse Dred Scott and urge Congressional legislation to protect slavery in the territories. Northern delegates, many of them strong Douglas supporters, refused, correctly pointing out that Dred Scott was extremely unpopular in their home states and that any Democratic ticket endorsing it would go down to certain defeat. When a minority report on the platform, authored by Douglas’ allies, was adopted on April 30, delegates from the Deep South walked out of the convention in protest.

But even with the most radical Fire-Eaters outside the convention, Douglas failed to muster the votes of the remaining delegates to secure the nomination. After 57 failed ballots, the convention adjourned, to reconvene six weeks later in the border city of Baltimore.

Lincoln Outmaneuvers the Field at the Republican Convention

If the site of the Democratic convention was disastrous for Douglas, the location of the Republican convention in Chicago could not have been more opportune for his arch-rival and fellow Illinoisan, Abraham Lincoln. As the convention began, William Seward remained the odds-on favorite for the nomination, even though his candidacy was weakened by the charges of radicalism against him in the wake of John Brown’s foray into Virginia. Lincoln’s able (if little-known) political supporters pursued a clever and deliberate strategy to present their candidate as a palatable second choice, should Seward falter.

See how William H. Seward went from being Lincoln's rival to the secretary of state under President Lincoln, with this video recording of historian Walter Stahr delivering a talk at the Kansas City Public Library.

Their strategy worked perfectly, owing to the fact that Lincoln alone had not offended any single faction of the party over the previous tumultuous years, while other potential nominees like Seward, the Ohioan Salmon Chase, and the Missourian Edward Bates had. Seward was, despite his backpedaling on John Brown, strongly identified with the “radical” antislavery wing of the party, while Chase, a former Democrat, had alienated many of the former Whigs by working closely with Democrats in the 1840s. Even parts of the Ohio delegation were wary of Chase, their opportunistic favorite son. Bates was anathema to many of the German immigrants in the Republican coalition because of his past association with the nativist Know-Nothing Party. Lincoln, for his part, was already a national figure from his famous 1858 debates with Douglas and his Cooper Union address. Plus, Lincoln was conveniently from the West – a region any Republican needed to carry to win the election.

As Lincoln’s allies had hoped and predicted, Seward failed to sew up the nomination on the first ballot, and his support melted away on the second. On the third ballot, Lincoln won the 1860 Republican nomination for president. Ironically (for a candidate so identified with the Kansas issue), Lincoln needed to win the nomination without the support of Kansas Territory’s Republican delegates, who remained loyal to Seward.

A Four-Man Race

Meanwhile, the Democrats tried again to reach consensus in Baltimore on June 18, six weeks after their debacle in Charleston. Once again, Southern delegates led by Fire-Eaters walked out of the convention when Northerners refused to adopt a resolution supporting the imposition of slavery on territorial residents. After two ballots, the remaining, dispirited Democrats finally nominated Douglas as their candidate for president, but everyone there knew their man—once the frontrunner to win the White House—had been dealt a serious political wound.

Southern Democrats left Baltimore much more upbeat. Most headed for Richmond, where on June 28, they gathered to nominate the proslavery standing vice president, John C. Breckenridge of Kentucky, for president. The party of Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson had been split in two by the slavery issue, and for the first time it placed two separate candidates before American voters: one sectional candidate who appealed mostly to slaveholders (Breckinridge) and a weakened national candidate (Douglas), who faced stiff competition from Republicans in the North and didn’t have a chance in the South.

In the toxic political atmosphere of 1860, Bell and his fellow compromisers faced an uphill battle even to be heard.

As if the presidential race wasn’t already complicated enough in 1860, ex-Know-Nothings and what was left of the once-proud Whig Party in the border and middle states, convened as the new Constitutional Union Party and nominated former Senator John Bell of Tennessee for President. Bell, a former Whig like Lincoln, advocated a grand compromise between the sections to preserve “the Union as it is.” In the toxic political atmosphere of 1860, Bell and his fellow compromisers faced an uphill battle even to be heard.

The Campaign

The split in the Democratic Party meant that there were essentially two separate presidential campaigns waged in the fall of 1860: one in the South between Breckinridge and Bell (although Douglas had some support in Southern cities among Irish immigrants), and another in the North between Lincoln and Douglas. Following a long tradition in American politics, Lincoln stayed put in Springfield, Illinois and let surrogates make his case for him, although he maintained a “hands-on” role in the campaign and wrote and received hundreds of letters and visitors.

Most of the time, Lincoln referred questioners to his voluminous published public comments from before the Republican convention. Douglas, on the other hand, struck out in a campaign much more reminiscent of modern canvasses, taking to the stump all over the country (all the while pretending to be “visiting his mother” or “tending to legal business”) to make his case for popular sovereignty as a final solution to the slavery issue.

For such a weighty election, the campaign of 1860 was almost subdued – and certainly less frenetic than the Republicans’ first nationwide canvass in 1856. Republicans who could read the electoral tea-leaves knew they had numbers on their side in New England and the upper-Midwest, which, due to an explosion in population, contained enough electoral votes for a candidate to win the race without support in the relatively smaller Southern states. Therefore there was little effort to persuade non-Republicans to vote for Lincoln and more emphasis placed on motivating the Republican faithful with odes to the party platform and nods to Lincoln’s thrilling life story. Republicans declined to campaign in the South at all, aside from rallies in a few contested border cities like Baltimore, Wheeling (a Virginia river town now in the state of West Virginia), and St. Louis.

The closest the campaign came to drama was in a handful of so-called “doubtful” states, where Northern Democrats and Republicans seemed evenly matched. Four years earlier, the Republican candidate John C. Frémont won all but five of the Northern states; flipping three or even two of the states won by James Buchanan would thus deliver the presidency to Lincoln without a single Southern ballot. So Lincoln and the savvy Republican Party concentrated money, newspapers, and persuasive German-language lecturers in Pennsylvania, Illinois, and Indiana, to great success. Despite last minute attempts at anti-Republican “fusion tickets” in states like Rhode Island, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania, Lincoln carried all the “Doubtful” states in 1860.

Republicans declined to campaign in the South at all, aside from rallies in a few contested border cities.

With Kansas’s petition for statehood bogged down in Congress, most residents believed the territory would play a relatively small role in the campaign. But Republicans kept the slavery issue in Kansas and Nebraska front and center, and several senior figures visited the region. Just six weeks before election day, William Seward heaped praise on the territory and its residents for their antislavery zeal.

"[You have] made Kansas as free as Massachusetts, and made the Federal Government, on and after the 4th of March next [inauguration day for the next president] the patron of Freedom – as it was at the beginning. You have made Freedom national, and Slavery sectional," Seward told a crowd of 6,000 people in Lawrence (6,000 people who couldn’t even cast a ballot in the election because they resided in a territory). “No other hundred thousand people in the United States have contributed so much for the cause of freedom.”

The Results

Turnout for the election was massive – 82 percent of eligible voters cast a ballot, making it the second highest percentage in American history, behind 1876. Lincoln won just under 40 percent of the popular vote nationwide, but he took a commanding majority of the votes in the Electoral College (180 out of 303; 28 more than he needed to prevail) without a single Southern state in his column.

Similarly, neither Bell nor Breckinridge won any states outside of their own region. Breckinridge came in second with 72 electoral votes (and a sweep of the Deep South), with Bell earning 39 by winning border states like Tennessee, Kentucky, and Virginia. Douglas – the only candidate with significant national appeal, and the only one to win electoral votes in more than one region – was a distant fourth with just 12 votes in the Electoral College. His only outright victory was in Missouri; he also won three of New Jersey’s seven electoral votes. But even if all of the anti-Lincoln voters agreed on a single “fusion” opponent, they still would have lost the election, 169 to 134.

Lincoln’s decisive victory did nothing to stem the disunionism that had hummed throughout the Bleeding Kansas crises, through John Brown’s raid, and the electoral campaign.

Lincoln’s decisive victory did nothing to stem the disunionism that had hummed throughout the Bleeding Kansas crises, through John Brown’s raid, and the electoral campaign. Even before President-elect Lincoln took the oath of office on March 4, 1861, seven states (South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas) chose to secede from the Union rather than be governed by a Republican president. The seceding states formed the Confederate States of America on February 4, 1861, and promptly seized control of the federal property and forts within their borders. In response to a call by President Lincoln for troops from each state to recapture this lost property, four other states (North Carolina, Tennessee, Arkansas, and Virginia) joined the Confederacy.

As the representatives of the South resigned their seats in Congress, Republicans were finally able to free the legislative logjam that had been set up by slaveholders and their allies. The new laws included: the Homestead Act, which distributed public lands free of charge to actual settlers; the Morrill Act to enable the formation of land-grant colleges; and, on January 29, 1861, the admission of Kansas to the Union as a free state under the new Wyandotte Constitution.

Whether slavery would be legal in Kansas—and in all territories—was the key question during the political crisis of the 1850s and the election of 1860. The election proved to be one of the most momentous in American history, coming in the midst of the nation’s severest crisis and paving the way for the Civil War. During that conflict, Kansas and the neighboring state of Missouri became the site of a particularly brutal form of guerrilla warfare, again taking center stage in the national drama over slavery, race, sovereignty and freedom.

Suggested Reading:

Earle, Jonathan. John Brown's Raid on Harper's Ferry: A Brief History With Documents. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's Press, 2008.

Egerton, Douglas R. Year of Meteors: Stephen Douglas, Abraham Lincoln and the Election that Brought on the Civil War. New York: Bloomsbury, 2010.

Green, Michael S. Lincoln and the Election of 1860. Carbondale and Edwardsville, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2011.

Luthin, Reinhard H. The First Lincoln Campaign. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1944.

Cite This Page:

Earle, Jonathan. "Kansas Territory, the Election of 1860, and the Coming of the Civil War: A National Perspective" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Sunday, April 28, 2024 - 12:24 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/essay/kansas-territory-election-1...

Rights/Licensing:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License