By Deborah Keating, University of Missouri – Kansas City

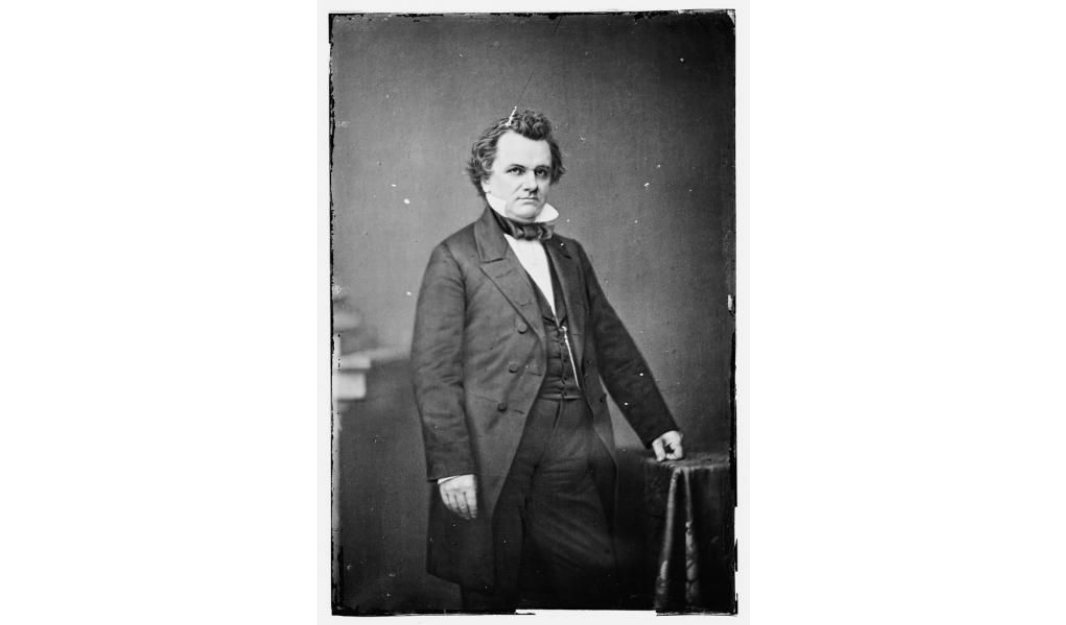

Biographical Information:

- Date of birth: April 23, 1813

- Place of birth: Brandon, Vermont

- Claim to fame: In an attempt to prevent secession with the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, his compromises backfired, helping to provoke the Civil War

- Nickname: "Little Giant"

- Political affiliations: Democratic Party

- Date of death: June 3, 1861

- Place of death: Chicago, IL

- Cause of death: Died of an attack of "acute rheumatism"

- Final resting place: Chicago, IL

More than most other antebellum politicians, Stephen Douglas is closely linked with “Bleeding Kansas” and the Missouri-Kansas “Border War.” A complex man, strongly partisan but committed to the Constitution as the ultimate law of the land, Douglas sponsored both the Compromise of 1850 and the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. Unintentionally, while trying to prevent secession by pacifying the Southerners, Douglas’s compromises stoked more violence and helped push the United States over the brink and into Civil War.

The facts surrounding Douglas’s early years are foggy, due in part to the various versions of his childhood he issued himself. He was born in Brandon, Vermont, on April 23, 1813. His father was Stephen Arnold Douglass (The younger Stephen dropped the second “s” in his name in 1846). His mother was Sara “Sally” Fisk Douglass. Stephen’s father was a physician but died in 1815 when Stephen was three months old. Sara Douglas moved to her brother Edward’s farm, where Stephen lived for the next 17 years. Douglas described his uncle alternately as a hard man who refused to allow him to attend school more than three months a year and as a loving uncle whose duty to his own family prevented helping Stephen with his education. Eventually Douglas left home to apprentice to cabinetmaker Nathan Parker in Middlebury, Vermont. He served Parker for nearly a year and then moved to Brandon, where he served as an apprentice to a cabinetmaker, Caleb Knowlton. Illness caused him to surrender that position, but once recovered, Douglas enrolled in Brandon Academy, where he remained until his mother remarried. In 1830 he moved with her to Clifton Springs, New York, and enrolled in Canandaigua Academy. After graduating, Douglas joined the Hubbell law firm and studied law for six months. The long internship required in the state of New York to become a lawyer was confining to a young man eager to make his fortune. In 1833, he decided to go west, clearly intent on finding a place where he could obtain a law license in less time. Douglas finally settled in Jacksonville, Illinois, after brief stops in Cleveland and St. Louis. After a winter spent reading and studying, Douglas obtained his law license in 1834.

...[he] continued to derive income from the plantation while consistently denying that he ever personally owned slaves.

Douglas married his first wife, Martha Martin, in 1847 and moved his home to Chicago. A year later, Martha’s father, Colonel Robert Martin, died and Martha inherited a cotton plantation with 100 slaves in Lawrence County, Mississippi. As part of the bequest, Douglas received one-third of the profits as compensation for managing the plantation. When Martha died in 1853, Douglas, acting as executor of her estate and guardian of their minor children, continued to derive income from the plantation while consistently denying that he ever personally owned slaves. He argued that his was a familial trust that honor bound him to respect for the sake of his children. However, his parsing did not satisfying his critics and he consistently had to defend himself against accusations of hypocrisy and self-serving political rhetoric.

Douglas’s position on slavery is one debated by historians. In an oft-quoted comment, Douglas claimed not to care whether slavery “was voted up or down, only that the decision be left to local majorities.” But his ambiguous position on the institution and the fact that he continued to own slaves, caused him political problems even into the famous debates with Abraham Lincoln in an 1858 campaign for the U.S. Senate. Lincoln pressured Douglas to say definitively whether he believed slavery to be morally right. Douglas argued that the question was moot because the Constitution of the United States allowed slavery to exist. He believed that only a state, through the voice of its inhabitants and their elected legislatures, had the right to decide to allow slavery within its borders. Out of this position grew Douglas’s idea of “popular sovereignty.”

Douglas’s irrevocable link with Kansas began when he championed the repeal of the Missouri Compromise of 1820. The Mexican War and the annexation of Texas again raised the issue of expansion of slavery into the new territories. Douglas’s Compromise of 1850 allowed two territories, Utah and New Mexico (both were territories formed out of the Mexican Cession of 1848) to decide whether to allow slavery within their borders at the time of their entry into the Union. Douglas believed that popular sovereignty would defuse the tension between the proslavery and antislavery factions. At issue was the balance of power in the U.S. Senate, and the Compromise of 1850 provided a possibility of preserving the delicate balance that existed between free and slaveholding states.

“There can be no neutrals in the war, only patriots – or traitors.”

Then in 1854, with Congress under pressure to provide more free land for settlement, Douglas introduced the Kansas-Nebraska Act. While the official purpose was to open the area for settlement, Douglas’s other agenda was to build a transcontinental railway from Chicago to the Gulf of Mexico. Unforeseen was how antislavery and proslavery factions would flood into the new territories to skew the vote in favor of their position. Violence broke out across the Missouri-Kansas border and the resulting struggle earned Kansas the sobriquet “Bleeding Kansas.” The political fallout from the Border Wars, combined with other inflaming events including John Brown’s raid at Harpers Ferry and the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision, eventually resulted in Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860 and the South’s secession from the Union.

Stephen Douglas was flexible in his position on many political issues but consistent in his belief that the Constitution was the law of the land. Secession was an anathema to him. He said after Fort Sumter, “There can be no neutrals in the war, only patriots – or traitors.” He supported Lincoln’s decision to respond to the attack on Fort Sumter and his call for 75,000 volunteers to counter the rebellion. At Lincoln’s request he visited several states, including the border states, giving speeches in support of the Union cause. Whether he ever understood the link between his policies and the South’s decision to secede is uncertain. Also speculative is how he would have reacted to the Emancipation Proclamation – an act that even Lincoln worried the Supreme Court would find unconstitutional.

These are unanswered questions of history. Stephen Douglas died of an attack of “acute rheumatism” in Chicago on June 3, 1861. He was 48 years old. A monument completed in 1883 near the shores of Lake Michigan in Chicago marks his tomb.

Suggested Reading:

J.T. Madison Cutts. “A Brief Treatise Upon Constitutional and Party Questions, and the History of Political Parties as I received it Orally from the Late Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois." North American Review. Vol. 103, No. 213. (Oct.,1866). 509-519.

Herbert Mitgang. The Fiery Trial: A Life of Lincoln. New York: Viking Press, 1974.

Roy Morris, Jr. The Long Pursuit: Abraham Lincoln’s Thirty-Year Struggle with Stephen Douglas for the Heart and Soul of America. New York: HarperCollins, 2008.

Martin Quitt. Stephen A. Douglas and Antebellum Democracy. Boston: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Cite This Page:

Keating, Deborah. "Douglas, Stephen A." Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Thursday, April 25, 2024 - 15:29 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/douglas-stephen