By Terry Beckenbaugh, U. S. Air Force Command and Staff College

View A Long and Bloody Conflict (Part I) in a larger map

Although the conflict in Virginia has commanded the lion’s share of attention and scholarship, Missouri and Kansas witnessed a tremendous amount of fighting during the American Civil War. Only two states, Virginia and Tennessee, had more actions fought on their soil during the Civil War than Missouri. Missouri was a strategically vital state for President Abraham Lincoln and the federal government’s war effort, and a case can be made that the Civil War started on the Missouri-Kansas border in the 1850s, during “Bleeding Kansas.” Missouri was split in its sentiments, and many Missourians fought on both sides of the war. By contrast, Kansans overwhelmingly fought for the Union.

This essay examines the military operations centered in Missouri and Kansas during the Civil War. The scale of the combat in Missouri and Kansas was smaller than the fighting east of the Mississippi River due to an underdeveloped railroad and road network and a small population, both of which logistically limited the size of the forces in the Trans-Mississippi. The initial fighting in Missouri zeroed in on controlling the vital Missouri River Valley and then focused on controlling the Mississippi and Arkansas Rivers. But the initial military operations in the region were drawn to perhaps the most strategically vital spot in the Mississippi River Valley at this stage of the war: St. Louis.

Camp Jackson Affair

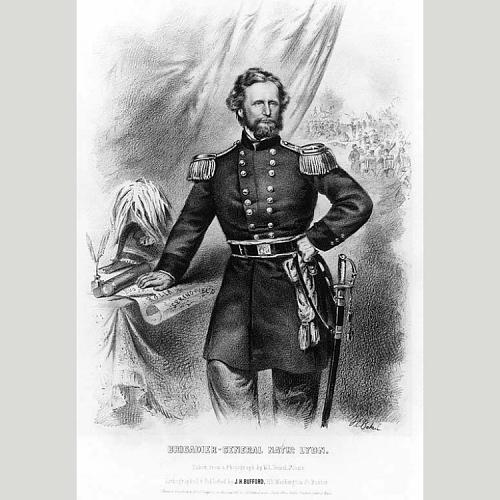

The situation in St. Louis reached a boiling point in early May 1861, when Missouri Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson called out the Missouri Volunteer Militia for maneuvers. Federal officer Nathaniel Lyon suspected Jackson of preparing the Missouri Volunteer Militia (MVM) to take over the state if Missouri seceded. Missouri did not officially secede, as the Missouri Constitutional Convention of 1861 voted overwhelmingly to remain in the union. Nonetheless, Lyon’s suspicions were confirmed when Jackson clandestinely cooperated with the Confederacy to have arms shipped to the MVM.

Lyon, who commanded the biggest weapons depot remaining in a slave state, at St. Louis, quite reasonably feared that his command was the MVM’s target. Lyon worked with pro-Union elements in St. Louis to raise a 6,000-man force of Missouri Unionists—much of it comprised of German immigrants—and U.S. Army regulars to confront the 600-man MVM at Camp Jackson, just outside of St. Louis. Federal forces surrounded the MVM contingent under General Daniel M. Frost and forced it to surrender on May 10. Many of the MVM prisoners refused to sign loyalty oaths to the United States government, so Lyon forced them to march through St. Louis to the U.S. arsenal, where they would receive parole due to a lack of prison facilities and underlying trust in the prisoners’ integrity.

The plans for parole proved to be a mistake. The march from Camp Jackson to the U.S. arsenal in St. Louis resulted in violence and bloodshed. Crowds lined the route and jeered at the mainly-German federal force, hurling rocks and other objects at the soldiers escorting the MVM prisoners. The federal force largely consisted of undisciplined soldiers instead of U.S. Army regulars, and the rattled soldiers fired into the crowd, killing 28 and wounding at least 50 more.

Lyon is generally credited with saving Missouri for the Union with his decisive actions in 1861, but he is also blamed for turning many middle-of-the-road Missourians against the Federal Government for his controversial actions in and around St. Louis in mid-1861.

The episode inflamed nativist sentiments and sparked several days of anti-German rioting in St. Louis. The “Camp Jackson Affair,” or “Camp Jackson Massacre,” on May 10, exacerbated an already volatile situation in St. Louis and throughout Missouri, polarizing the populace in the hinterland. Lyon is generally credited with saving Missouri for the Union with his decisive actions in 1861, but he is also blamed for turning many middle-of-the-road Missourians against the Federal Government for his controversial actions in and around St. Louis in mid-1861. Although Missouri initially rejected secession and tried to remain militarily neutral, the Confederacy’s firing on Fort Sumter on April 11, 1861, forced everyone to take a side.

Price-Harney Agreement

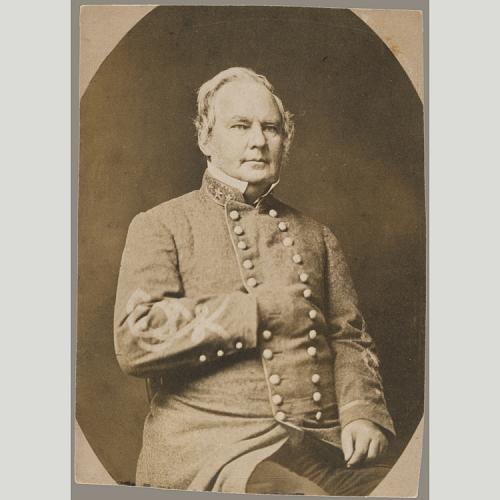

Although Jackson clearly wanted to secede, he did not want to make the first move and alienate the majority of the population that wished to stay neutral. U.S. Brigadier General William S. Harney’s absence from St. Louis allowed Lyon to command the city, but Harney’s return restored a more moderate Unionist officer. Accordingly, Harney negotiated with Confederate-leaning Missouri State Guard commander Sterling Price to keep the situation from spiraling out of control.

The Harney-Price Agreement, signed on May 21, 1861, placed federal troops in charge of St. Louis and its vicinity, while Price’s newly-formed Missouri State Guard (MSG) was responsible for the rest of Missouri. Pro-Confederate civilians were not to be molested in St. Louis by the federals, while the Missouri State Guard similarly agreed not to accost Unionists in Missouri’s hinterland. While the Price-Harney agreement cooled tempers in the state, it did not placate Unionists who agitated to place Missouri squarely on the Union side of the ledger.

Planter’s House Meeting

The truce could not last. Reports that the Missouri State Guard harassed Unionists throughout the state trickled into St. Louis. This gave St. Louis Unionists plenty of ammunition with which to bombard the Lincoln administration with calls for decisive action against the Missouri State Guard. Lincoln responded by promoting Lyon to brigadier general and then relieving Harney of command on May 30. Lyon’s promotion pleased the Unionists, and with Lincoln’s implicit mandate to take action, Lyon promptly did so. He called Governor Jackson and Price to a meeting at the Planter House Hotel in St. Louis under a flag of truce on June 11. What Jackson and Price assumed to be a negotiation between themselves, Lyon, and U.S. Congressman Frank Blair Jr. proved to be nothing of the sort.

Lyon refused to honor the Price-Harney agreement and absolutely refused to accept any limitations on federal action in Missouri. The meeting lasted four hours and grew contentious before Lyon finally ended the meeting with a dramatic speech:

Rather than concede to the State of Missouri the right to demand that my government shall not enlist troops within her limits, or bring troops into the State whenever it pleases, or move troops at its own will into, out of, or through the State; rather than concede to the State of Missouri for one single instant the right to dictate to my government in any matter, however unimportant, I would see you, and you, and you, and you, [pointing to each man in the room] and every man, woman, and child in the State dead and buried. This means war. In an hour one of my officers will call for you and conduct you out of my lines.

With that Jackson and Price exited the room and prepared for war, while Lyon did the same.

Boonville to Wilson’s Creek

View A Long and Bloody Conflict (Part I) in a larger map

Lyon wasted little time in chasing Jackson and Price across the state. Federal forces captured Jefferson City on June 15, with little resistance from the Missouri State Guard. Lyon caught up with Jackson (who had taken command of the MSG while Price recuperated from an illness) on June 17, just outside of Boonville, and routed the small MSG force that tried to delay the federals. Casualties were light on both sides, but the small victory had a major consequence - the victory at Boonville secured the bulk of the Missouri River Valley in central and eastern Missouri for the federals. Jackson continued his retreat to Cowskin Prairie in the extreme southwest corner of Missouri, where he reunited with Price. The two hoped to train and equip the MSG into a real fighting force capable of ejecting federal forces from the state. They just needed some breathing space.

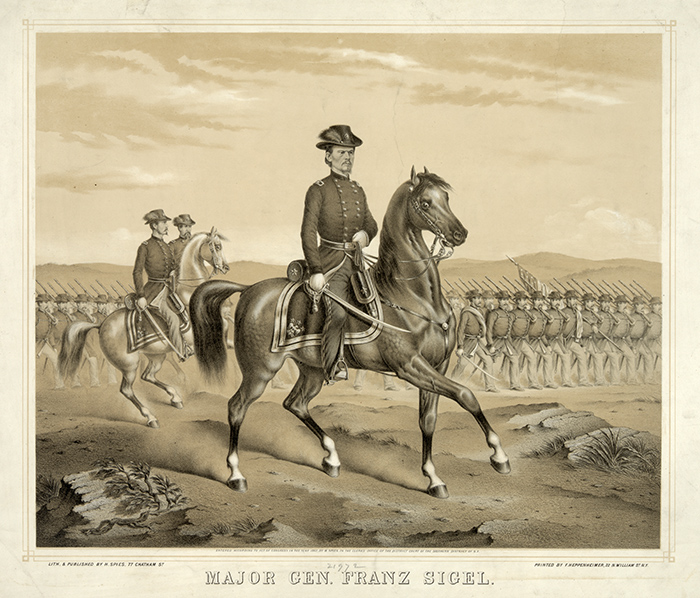

Lyon attempted a pincer movement to destroy the Missouri State Guard before it received reinforcements from Arkansas and the rest of Missouri. This attempt failed when Franz Sigel, a German immigrant and politician-turned-Union colonel (and soon to be promoted to brigadier general on August 7), unsuccessfully attacked the MSG outside of Carthage on July 5. Although this was a minor battle, it gave Confederate-leaning Missourians their first good news of the conflict. Sigel retreated and joined Lyon’s federal force at Springfield. Price and Jackson used the breather gained by the victory at Carthage to equip and train the Missouri State Guard to turn it into a disciplined fighting force.

Another advantage gained from the victory at Carthage was that Confederate forces in Arkansas, led by Brigadier General Ben McCulloch, a former Texas Ranger, were now closer to the MSG than were Lyon’s federals. When the MSG and Confederate forces combined, they more than doubled Lyon’s men. The allied MSG-Confederate force, co-commanded by Price and McCulloch, moved northeast toward Springfield and set the stage for battle.

Lyon’s Army of the West attacked the larger MSG-Confederate force at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek on August 10. Lyon allowed Sigel to talk him into a bold plan that called for splitting his already-smaller force in two and attacking the allied force in front and in the flank. The plan was extremely risky and needed a lot of moving parts to fit together seamlessly for it to work. It did work initially, as Lyon’s early morning attack surprised both Price and McCulloch, who rallied their men to defend against the pugnacious Lyon.

The Union offensive depended entirely on Sigel, who commanded the federal flanking force. But Sigel was not up to the challenge. His attack started well, but Sigel failed to place skirmishers in front of his force to inform him of enemy movements ahead of his troops. That negligence turned into disaster when his units mistook the Confederate 3rd Louisiana regiment for the Union 1st Iowa regiment (unfortunately, the Iowa soldiers wore grey, causing the confusion), the 3rd Louisiana launched a devastating assault that chased Sigel and his men from the field. To make matters worse, Sigel so hastily left the field that he neglected to inform Lyon or anyone else of his failed mission. The Federals atop Bloody Hill now faced the combined might of the Missouri State Guard and the Confederate forces.

The Battle of Wilson’s Creek was over, and the casualties (killed, wounded, and missing) were shockingly high.

Lyon’s untimely death at mid-morning, during the fight on Bloody Hill, left Major Samuel Sturgis in command of the remainder of the Army of the West. He decided that with no news from Sigel, with casualties mounting, and with supplies running out, the federals had to leave the field. The Battle of Wilson’s Creek was over, and the casualties (killed, wounded, and missing) were shockingly high: over 1,300 for the Federals and over 1,200 for the MSG-CSA force. Lyon’s death left the federals leaderless for the immediate future, as they fell back to Rolla.

Lyon, who just two months before had promised to see every Missourian dead rather than side with the Confederacy, ironically became the first Union general to die in the war. Furthermore, the MSG now controlled large sections of the interior of Missouri, especially the southwest portion of the state. Due to personal animosity between Price and McCulloch, the latter took his Confederate forces back into Arkansas. Without McCulloch, Price could not threaten St. Louis, but that did not prevent the man, known affectionately by his soldiers as “Old Pap,” from taking the war to the federals.

Siege of Lexington; Federal Change of Command

Listen to historian Terry Beckenbaugh describing the first year of the Civil War in Missouri at the Kansas City Public Library.

After Wilson’s Creek, Price took the Missouri State Guard north of the Missouri River and captured Lexington, Missouri. The Battle of the Hemp Bales, as that fight became known, proved to be the high point of the war for Price and the MSG, and while not a disastrous setback for the Union war effort in Missouri, it did force the Lincoln administration to make some kind of change in the West. On November 9, Lincoln replaced Department of the Missouri commander Major General John C. Frémont with West Point graduate Major General Henry W. Halleck. Halleck, in turn, appointed another West Pointer, Brigadier General Samuel Ryan Curtis to be in charge of the remnants of Lyon’s Army of the West and the new federal recruits in training at Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis. Curtis christened this force the Army of the Southwest. The new year of 1862 promised to see crucial military activity in the Missouri and Kansas region.

Continue Reading with Part II of “A Long and Bloody Conflict”. . .

Suggested Reading:

Castel, Albert E. Civil War Kansas: Reaping the Whirlwind. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1997.

Gerteis, Louis. The Civil War in Missouri: A Military History. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2012.

Gerteis, Louis S. Civil War St. Louis. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004.

Parrish, William E. Turbulent Partnership: Missouri and the Union, 1861-1865. Columbia: The University of Missouri Press, 1963.

Piston, William Garrett and Richard W. Hatcher III. Wilson's Creek: The Second Battle of the Civil War and the Men Who Fought It. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000.

Cite This Page:

Beckenbaugh, Terry. "A Long and Bloody Conflict: Military Operations in Missouri and Kansas, Part I" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Friday, April 26, 2024 - 17:54 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/essay/long-and-bloody-conflict-mi...

Rights/Licensing:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License