By Russell S. Perkins, University of Saint Mary

Biographical information:

- Date of birth: January 16, 1815

- Place of birth: Westernville, New York

- Claim to fame: Western Theater Union Army commander; General-in-chief of U.S. armies

- Nickname: "Old Brains"

- Date of death: January 9, 1872

- Place of death: Louisville, Kentucky

- Cause of death: Complications of heart and liver disease

- Final resting place: Green-Wood Cemetery, New York City, NY

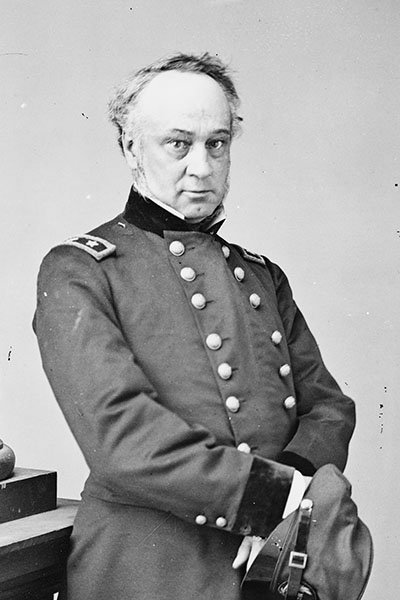

Henry Wager Halleck was one of the most prominent Union generals in the American Civil War. Though primarily remembered for his bureaucratic leadership, poor handling of troops in the field, and often prickly relationships with subordinate army commanders, Halleck had a first-class mind that affected the course of the Civil War based on his first experience of large-scale command in Missouri.

Halleck was born in rural Westernville in upstate New York on January 16, 1815. As a youth his passion for intellectual pursuits led him to flee his father’s farming life for the more rarified household of his uncle, David Wager, a prominent former New York state congressman. From that upbringing, young Halleck attended two colleges before finally settling on a West Point education at the age of 20. Graduating third in his class in 1839, Halleck quickly established himself as an authority on coastal fortifications, earned a promotion, and was sent by Major General Winfield Scott to France for further study. Returning from France, Halleck embarked on a lecturing tour that culminated in the publication of his most famous work, Elements of Military Art and Science in 1846.

In the same year, the United States declared war on Mexico and Halleck was sent to California, which caused him to miss the major fighting but further solidified his academic reputation with his translation of Antoine-Henri Jomini’s study of Napoleon. Though Halleck had secured a strong place in the officer corps of the U.S. Army and a brevet promotion to captain for meritorious service, his mind increasingly turned to other fields. He became the principle author of the California Constitution, narrowly lost election to be one of California’s first senators, and joined a law practice so successful that he resigned from the Army in 1854, married into a prominent political family, and started a family of his own.

With the outbreak of the Civil War, Halleck was a natural choice for high command and appointed a regular major general in the Army. His first assignment was to command the Department of Missouri and relieve its current commander, Major General John C. Frémont which he did by November 9, 1861. While the regular Confederate military presence in Missouri had been severely weakened by this point, Halleck faced the equally tremendous tasks of organizing his department after months of corruption and securing the state against depredation by the anti-Union guerrilla forces of Missouri bushwackers and their pro-Union counterparts, Kansas jayhawkers. Organizationally and politically, Halleck accomplished a great deal as he eliminated unnecessary bureaucracy and repealed many of Frémont’s standing orders, including the attempted emancipation of Missouri’s slaves. These actions helped bring military and political stability to his area of operations which, in addition to Tennessee, included the still loyal slave states of Missouri and parts of Kentucky.

Halleck was overly cautious in his advance... and the Confederate Army of Tennessee, at only half the strength of Halleck’s army, escaped intact.

Militarily, Halleck was blessed with a strong cadre of promising officers. Ulysses S. Grant, then a brigadier general, won victories at Forts Henry and Donelson opening the way for federal advances into Tennessee. Meanwhile, Confederate threats to the southwestern and southeastern portions of Missouri were removed by the victories of Samuel Curtis at Pea Ridge, Arkansas, and by John Pope at Island No. 10. It was only after the Battle of Shiloh, on April 6-7, 1862, that Halleck’s command performance faltered. Holding Grant responsible for the Confederate surprise attack, Halleck left his St. Louis headquarters and took personal command of the armies in the field, consolidated them, relegated Grant to the ineffectual position of second-in-command, and moved against Corinth, Mississippi. Though he captured the city on May 30, 1862, Halleck was overly cautious in his advance, which consumed nearly two months to move 22 miles, and the Confederate Army of Tennessee, at only half the strength of Halleck’s army, escaped intact.

Halleck’s missteps at Corinth were not nearly enough to invalidate his achievements in keeping Missouri under federal control, directing or approving military maneuvers penetrating hundreds of miles into Confederate states, and increasing the overall effectiveness of his large department. This performance led President Abraham Lincoln to appoint Halleck general-in-chief of the Union armies with headquarters in Washington D.C. Halleck assumed his new responsibilities on July 23, 1862, and quickly relegated himself into an advisory role rather than that of a military strategist, distancing himself from responsibility for Union battlefield defeats. While that decision played to Halleck’s strengths as a military theorist, organizer, and administrator, it also alienated his subordinate commanders in the field and damaged his ability to advise the president on military operations against the Confederacy. Consequently, Halleck lost much of his scholarly reputation and his overall military effectiveness was severely impaired.

[Halleck] attempted to curb the disorderly vigilante violence in Missouri by instituting the death penalty for guerrillas and imprisonment for those aiding their efforts.

Though Halleck’s attention was dominated by the more orderly clash of armies in the Eastern and Western theaters throughout 1862 and 1863, the chaotic guerrilla war in Missouri did not go unnoticed. Even before Halleck’s promotion, he attempted to curb the disorderly vigilante violence in Missouri by instituting the death penalty for guerrillas and imprisonment for those aiding their efforts. The intent was to force combatants into the armies and bring the fighting into patterns recognized by the French military theorists he knew so well. The effect of the harsh measures instead galvanized the determination and violence of the guerrillas in Missouri. Halleck, later as general-in-chief, sought legal remedies in his effort to subdue rebellious non-military populations. Consulting with Franz Lieber, an early authority on military law, Halleck drafted what became President Lincoln’s General Orders No. 100 in the spring of 1863, guiding military officers in the general rules of war, the treatment of civilians, and penalties for guerrillas. These orders did little to decrease guerrilla operations but provided the legal foundation for federal Brigadier General Thomas Ewing’s General Order No. 11 that forcibly displaced the population of four western Missouri counties and further alienated the people of the state on both sides of the conflict.

When Ulysses S. Grant was promoted to lieutenant general and made general-in-chief of the Union armies in March 1864, Halleck was moved to the position of chief-of-staff. In that role, Halleck performed admirably and ensured that steady streams of recruits and supplies went uninterrupted to the heavy fighting along the front lines in Virginia, Georgia, and west of the Mississippi River for the remainder of the Civil War.

With the end of the war in 1865, and after serving as a pallbearer at Lincoln’s funeral, Halleck was sent back to California in command of the Division of the Pacific, which expanded during his tenure to include new territory in Alaska with fresh problems of administration and tension with the British. His command in California was a successful one, and by 1869 Halleck was transferred eastward to apply his administrative talents to the problems of Reconstruction. Assuming command of the Military Division of the South with headquarters in Louisville, Kentucky, he resumed his pattern of delegating military authority to commanders on the scene of potential trouble while keeping the administrative details to himself. Henry W. Halleck died at his post in Louisville from complications of heart and liver disease on January 9, 1872, one week before his 57th birthday.

Suggested Reading:

Ambrose, Stephen E. Halleck: Lincoln’s Chief of Staff. 1960. Reprint, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996.

Gilmore, Donald L. Civil War on the Missouri-Kansas Border. Gretna, LA: Pelican, 2006.

Marszalek, John F. Commander of All Lincoln’s Armies: A Life of General Henry W. Halleck. Boston: Harvard University Press, 2004.

Cite This Page:

Perkins, Russell S.. "Halleck, Henry Wager" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Thursday, April 18, 2024 - 02:12 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/halleck-henry-wager