By Christopher Phillips, University of Cincinnati

Biographical information:

- Date of birth: April 4, 1806

- Place of birth: Fleming County, Kentucky

- Claim to fame: Missouri State Representative, 1836-1848; Missouri Senator, 1848-1852; Governor of Missouri, 1861

- Political affiliations: Democratic Party

- Date of death: December 6, 1862

- Place of death: Little Rock, Arkansas

- Cause of death: Stomach cancer

- Final resting place: Sappington Cemetery, Arrow Rock, Missouri

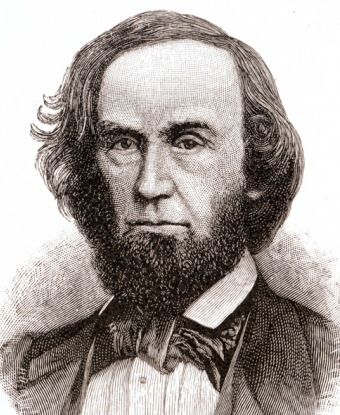

Claiborne Fox Jackson, the pro-Confederate governor of Missouri at the outset of the Civil War, was born in rural Fleming County, Kentucky on April 4, 1806. The son of a moderately prosperous tobacco farmer and slaveholder, Jackson received only slight formal education before migrating with three older brothers in 1826 to Franklin, Missouri, where he engaged in business.

In 1832, during the Black Hawk war, a territorial conflict with members of the Sauk, Fox, Potawatomi, Ho-Chunk, Meskwaki, Kickapoo, and Ottawa tribes in and around Illinois, Jackson organized a company of Howard County volunteers and served as its captain. Afterwards, he moved to Saline County and began his career in banking. There he met and married Jane Sappington, a daughter of Dr. John Sappington, who was a prominent local physician and businessman who marketed quinine pills in the Southern river regions as a treatment for malarial fevers. Following Jane’s death within months of their marriage, Jackson married her sister, Louisa Sappington. Then, following Louisa’s death in 1838, Jackson married a third daughter of Dr. Sappington, Eliza, whose bigamist husband had left her with five children.

A lifelong proslavery Democrat, Jackson was elected to the state legislature in 1836 and served one term before retiring to private banking in Fayette, a well-known center of political power in Missouri. In 1842, Jackson, then a supporter of U.S. Senator Thomas Hart Benton, was again elected to the state legislature. Within two years he had been chosen speaker of the house, a position he would hold for two consecutive terms, before being elected to the state senate in 1848.

In the legislature, Jackson became allied with the “Central Clique,” a group of state-level, proslavery politicians who hailed from Missouri River counties near Fayette, where slaveholding was densest. Their target increasingly became their once-leader, Benton, who, though still a Democrat, had moved since the war with Mexico from a reliable proslavery advocate to Free-Soilism, or the opposition to the extension of slavery into the Western territories. In 1848, Jackson sponsored a set of resolutions, approved jointly in the General Assembly, asserting that Congress did not have the authority to limit slavery in the territories and instructing Missouri’s U.S. senators (then elected by the state legislature) and representatives to vote exclusively in favor only of legislation supporting slavery’s extension. They soon became known as the “Jackson Resolutions.”

The political furor that resulted cost Benton his seat in 1850, thus ending his 30-year tenure in the U.S. Senate and Jackson his state senate seat two years later. Although he sought several, Jackson held no elected office during the 1850s. He served as chairman of the state Democratic Central Committee, and in 1858 he was appointed Missouri's first state bank commissioner. In 1856, at Sappington’s death, Jackson inherited a large portion of his father-in-law’s estate near Arrow Rock, including the homestead. By 1860 he owned 48 slaves, which, while relatively small by the standards of the Deep South, placed him in the ranks of Missouri’s planter elite.

Fear of antislavery Republicans allowed Jackson to win the state’s governorship against three other candidates.

In 1860, against the backdrop of the presidential election, fear of antislavery Republicans allowed Jackson to win the state’s governorship against three other candidates. Staunchly supportive of Southern rights, he gained broad-based support by claiming moderate stances designed to achieve the unity of a long-divided Democratic Party.

In 1860, following Abraham Lincoln’s election, Jackson’s former moderation quickly turned into covert activism to effect Missouri’s secession. When the state convention voted overwhelmingly against in March 1861, Jackson organized the state militia, encouraged the legislature to pass a Military Bill to give him more power to arm the state, and clandestinely secured artillery from the Confederacy.

After Fort Sumter, Jackson refused Lincoln’s call for troops. Then, after a failed June 11 conference with Sterling Price, commander of the state militia, and federal leaders at St. Louis’s Planters’ House Hotel, Jackson called for 50,000 State Guard volunteers to defend the state. He was present with the State Guard in its defeat by Union General Nathaniel Lyon’s troops at the Battle of Boonville on June 17. Retreating with these troops toward the southwestern corner of the state, Jackson led them to victory over Franz Sigel’s Union troops at the Battle of Carthage on July 5.

In late August 1861, after the state’s provisional government ousted him from the governorship, Jackson returned to Missouri from Richmond, Virginia, where he and former U.S. Senator David Rice Atchison secured military and financial support from the Confederate government. He accompanied Price’s advance to Lexington and then led the “rump session” of the legislature in Neosho on October 28-30, which voted for secession and authorized membership in the Confederacy. When Union General Samuel R. Curtis forced Price’s State Guard out of the state in early 1862, Jackson set up his exiled government in Arkansas. It cooperated fully with Confederate authorities during the remainder of war, but it never actually controlled Missouri. The exiled Missouri government did manage to survive longer than Jackson, who died of stomach cancer in Little Rock on December 6, 1862.

Suggested Reading:

Parrish, William E. Turbulent Partnership: Missouri and the Union, 1861-1865. Columbia: The University of Missouri Press, 1963.

Phillips, Christopher. Missouri's Confederate: Claiborne Fox Jackson and the Creation of Southern Identity in the Border West. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2000.

Cite This Page:

Phillips, Christopher. "Jackson, Claiborne Fox" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Wednesday, April 24, 2024 - 09:06 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/jackson-claiborne-fox