By Deborah Keating, University of Missouri – Kansas City

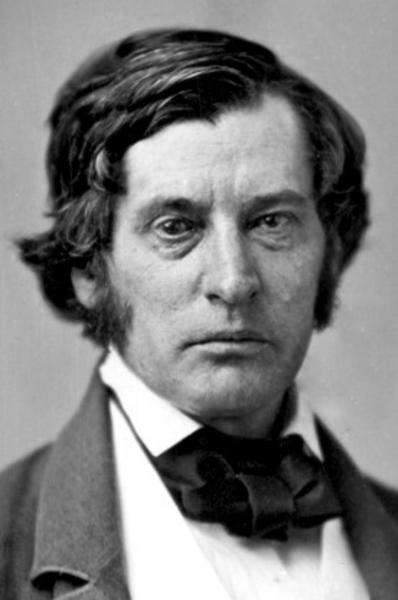

Biographical Information:

- Born: January 6, 1811

- Place of birth: Boston, Massachusetts

- Claim to fame: antislavery U.S. Senator (1851-1874); assaulted by Representative Preston Brooks on the floor of the U.S Senate (May 22, 1856).

- Political affiliations: Republican Party

- Date of Death: March 11, 1874

- Place of Death: Washington, D.C.

- Final resting place: Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Charles Sumner was a man known for political extremes in a time when the United States was flush with political extremists. As the nation hurdled toward Civil War over the issue of slavery, radicals like Sumner on both sides of the debate aggravated dissension with histrionic rhetoric inflammatory even for the period. Sumner used his powerful voice and speaking ability in support of the abolitionist cause and his acerbic intelligence against those who argued for expansion of slavery into Kansas and enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act. His verbal attacks on Southern legislatures and their constituents led to his being physically attacked on the floor of the House in 1856; an attack which gained him sympathetic support in the North but left him permanently impaired.

Sumner inherited his passionate dislike for slavery from his father, Charles Pinckney Sumner, who was an early abolitionist. Father of nine, of whom young Charles and his twin sister Matilda were the eldest, Charles Pickney Sumner also taught his children that freedom without justice was pointless. The younger Charles followed his father into the practice of the law after graduating from Harvard Law School. He was admitted to the bar in 1834 and set up a practice in Boston with a partner, George Stillman Hillard.

In December 1837, like so many young men of the day, Sumner traveled to Europe, joining some of his friends in Paris. Determined to learn French, he settled in rooms near the Sorbonne where he embraced the French student lifestyle despite suffering terribly from the damp and cold. Historian David McCullough traces Sumner’s political awakening to a moment at the university when Sumner observed “two or three black, or rather mulattos . . . dressed quite a la mode and have the easy, jaunty air of young men of fashion . . . .” Sumner is further quoted as observing, “It must be then that the distance between free blacks and whites among us is derived from education, and does not exist in the nature of things.” This represents a change from his earlier impressions upon observing slaves working in the fields when, per McCullough, Sumner “felt only disdain for them.”

Sumner thrived in Paris, and he returned to America in 1840 at 6 feet, 4 inches tall, stately, full framed, and with a commanding manner. He resumed his law practice but was more interested in social issues, including the reform of prisons and the public education system of Massachusetts. In his role as social reformer, he was frequently called upon to speak to supporters and became well known for his rhetorical style and sonorous voice. As was typical of the age, his lectures were replete with classical and biblical references as well as with much description and hyperbole.

Reading An Appeal in Favor of that Class of Americans Called Africans (1833), by Lydia Maria Child, solidified Sumner’s antislavery sentiments and he became a radical abolitionist. In 1847, as a “Conscience Whig,” he publically opposed the Mexican-American War out of concern that victory would lead to the expansion of slavery. In his speech he argued,

A war of conquest is bad; but the present war has darker shadows. It is a war for the extension of slavery over a territory which has already been purged by Mexican authority from this stain and curse.

Dissatisfied with the Whig’s conciliatory position on slavery, Sumner helped form the Free Soil Party in 1848. In 1851 he was elected to the Senate and became the leading opponent to the expansion of slavery but also advocated for its abolition where it already existed. As a leader of the Radical Republicans, he argued against any compromise on the slavery issue. “I think slavery a sin, individual and national and I think it the duty of each individual to cease committing it,” he wrote.

Two days before the May 21, 1856, Sack of Lawrence, Sumner delivered his famous “The Crime against Kansas” speech to a packed Senate. As he so often did, he peppered his speech with personal attacks on fellow senators whom he blamed for “Bloody Kansas” and who opposed his point of view.

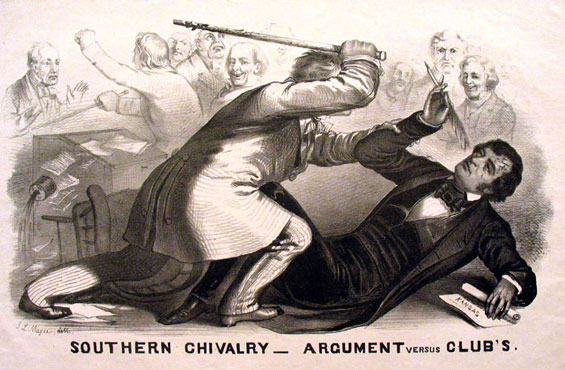

He singled out Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois and Senator Andrew Butler of South Carolina as the perpetrators of this “crime,” using language “of a kind traditionally not tolerated in the Senate, in the words of McCullough. Two days later, Preston Brooks, a relative of Butler’s responded in defense of his uncle and the honor of his state. Brooks attacked Sumner who was trapped in his Senate desk, using a wooden cane with a gold head. Managing to stumble free, Sumner collapsed, lapsing into unconsciousness. Brooks continued to beat the unconscious man until his cane broke and then calmly left the chamber. Others were prevented from helping Sumner by Laurence M. Keitt of South Carolina, who held them off with a pistol.

Managing to stumble free, Sumner collapsed, lapsing into unconsciousness. Brooks continued to beat the unconscious man until his cane broke and then calmly left the chamber.

The attack had political ramifications as well as personal ones. Charles Sumner never fully recovered emotionally from the attack, and modern analysis of his symptoms suggests that he suffered from post-traumatic stress syndrome. Even after the external signs of the attack were gone, he found walking difficult, suffered headaches and could not tolerate spending time in the Senate. After some months he journeyed to Paris to recuperate. The difference in his physical appearance upon departing New York and arriving Paris seven days later was astonishing. His stamina returned and he engaged in the social life of Paris, visited the provinces and then toured Europe before heading home.

When he returned to Washington in December 1857, he was threatened with violence should he return to the Senate. He did return for two weeks but took no active part in the Kansas statehood debates underway at the time. He found he could not tolerate the work of the Senate and on his doctor’s recommendation, he returned to Paris in May 1858. Through it all the Massachusetts voters allowed him to retain his Senate seat, even though he did not actively serve for over three years.

Sumner finally returned to the Senate in 1859 and took up in the same vein, refusing to modify his attacks on the proslavery factions. Unlike Lincoln, who “spoke of slaveholders . . . as men and women enmeshed in a system for which they could not disentangle themselves,” Sumner’s attacks on his opponents continued to be considered vicious and harsh, even by his supporters. When war finally came and the Southerners resigned from the Senate, Sumner became chairman of the Committee on Foreign Relations. He lobbied Lincoln for immediate emancipation of the slaves as a way to keep Britain from recognizing the Confederacy and providing it with financial support. He was also publicly outspoken that the primary goal of the war was the abolition of slavery, despite Lincoln’s insistence to the contrary. Sumner was often critical of Lincoln’s policies, but nonetheless, Lincoln continued to consult with him, crediting him as the voice of the people on the conservative right.

As passionate for black civil rights after the war as he had been for emancipation during the war, Sumner saw black suffrage as an inherent right under the Constitution. He also believed that the only way to keep recalcitrant Southerners from regaining political and economic dominance was to ensure the rights of the freed slaves were protected by law. To this end he lobbied hard, introducing the first Civil Rights Bill in 1872. The bill failed but he resubmitted it in the following Congress and continued to advocate for it until his death.

His position on Reconstruction was typically unbending. While he did not advocate capital punishment or imprisonment for Southern leaders, he did argue that the Southern states had abandoned their rights to inclusion in the Union and must reenter only under conditions imposed by Congress. In this vein, he voted to override many of Andrew Johnson’s vetoes and cast a “Yea” vote for his impeachment.

Charles Sumner died of a heart attack on March 11, 1874, and was buried in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His biographers, even when trying to be kind, describe him as an unyielding moralist with absolute confidence in his own judgment. Whether he could have been more effective had he adopted a different style when extremism was the rule, rather than the exception, is debatable. What is certain is that at a time when most men saw black Americans as inferior, Charles Sumner fought unrelentingly for black equality long after others had grown weary of the battle.

Suggested Reading:

Donald, David Hubert. Charles Sumner and the Coming Civil War. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1960.

Donald, David Hubert. Charles Sumner and the Rights of Man. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1970.

Foner, Eric. Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

McCullough, David. The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011.

Stampp, Kenneth. America in 1857: A Nation on the Brink. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Cite This Page:

Keating, Deborah. "Sumner, Charles" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Saturday, April 20, 2024 - 11:36 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/sumner-charles