By Deborah Keating, University of Missouri-Kansas City

Biographical information:

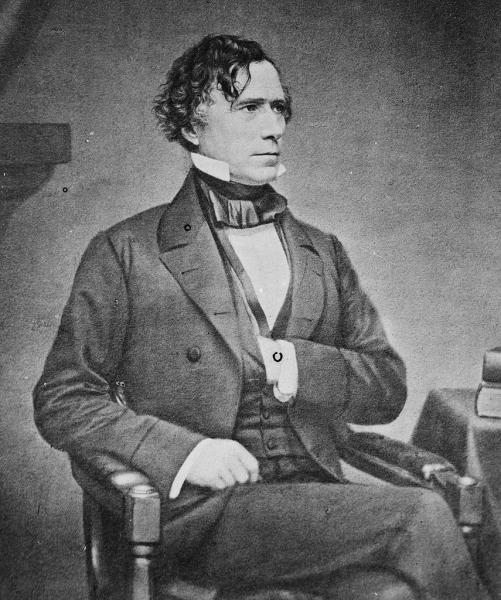

- Date of birth: November 23, 1804

- Place of birth: Hillsborough (present-day Hillsboro), New Hampshire

- Major offices held: U.S. Congressman, March 4, 1833-March 4, 1837; U.S. Senator, March 4, 1847-February 28, 1842; U.S. President, March 4, 1853-March 4, 1857

- Nickname: "Young Hickory of the Granite Hills"

- Political affiliations: Democratic Party

- Date of death: October 8, 1869

- Place of death: Concord, New Hampshire

- Cause of death: Cirrhosis of the liver

- Final resting place: Old North Cemetery, Concord, New Hampshire

History often measures prominent individuals by what they did not accomplish as much as by what they did. Franklin Pierce, the 14th President of the United States, was one such person whose failings overshadowed his contributions. Irrevocably associated with the Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854) and “Bleeding Kansas,” Pierce is ranked by many historians as the worst of all the nation’s presidents. A strict constitutionalist and supporter of the Southern position on slavery, as well as an outspoken critic of Abraham Lincoln, Pierce earned the disdain of his contemporaries and the low esteem of history. But as is true with most famous figures, Pierce’s impact on the nation’s legacy was not so one-dimensional.

Born in Hillsborough, New Hampshire, on November 23, 1804, Franklin Pierce was the fifth of eight children born to Benjamin Pierce and his second wife, Anna Kendrick. Benjamin worked hard to provide his sons an education. At first Franklin’s academic career was less than stellar; however, when he graduated from Bowdoin College in 1824 he was third in his class. After graduation he studied law and was admitted to the New Hampshire bar in 1827. Pierce established a law practice in Hillsborough, where, in 1828, his political career began when he was elected Hillsborough town moderator.

Pierce was an active campaigner for Andrew Jackson in the 1828 election. Riding the Democratic victory over the Federalist Party, he was elected to the U.S. Congress in 1833. Between that election and the beginning of the March 1834 congressional term, Pierce married Jane Means Appleton, who came from an elite Whig family. Shortly after the wedding, Franklin left for Washington, where he joined the fight to prevent renewal of the Bank of the United States’ charter.

The abolitionist movement was also gaining momentum. Pierce understood the threat to the Union if Congress failed to find a peaceful solution to the debate over the expansion of slavery. Nonetheless, he believed the Constitution protected the institution and he supported the Southern position. He continued to hold this position when elected to the U.S. Senate in 1837. The fight to ban slavery in the District of Columbia was underway and Pierce joined with John C. Calhoun to defeat the attempt. But in 1842, leaving the fight over slavery to others, Pierce resigned from the Senate and returned to New Hampshire to practice law and spend more time with his family.

Pierce wanted the gravitas that active military service brought a politician’s resume.Politics was in his blood, however, and in the same year he left the Senate, Pierce accepted the chairmanship of the New Hampshire State Democratic Party. In 1844 he supported James Polk in the presidential election. His reward was appointment as U.S. Attorney for the District of New Hampshire. When the Mexican American War broke out in 1846, Pierce sought a commission in the Army. Already a colonel in the state militia, which he joined before his marriage in 1831, Pierce wanted the gravitas that active military service brought a politician’s resume. Appointed commander of the 9th Infantry Regiment in February 1847, he fought in Mexico until a knee injury suffered when his horse fell on him during the Battle at Contreras, limiting his ability to lead his troops effectively. He finally returned to New Hampshire in December 1847, trailed by accusations of cowardice that plagued him for the rest of his political career, even after Ulysses S. Grant published testimony to Pierce’s bravery in his autobiography.

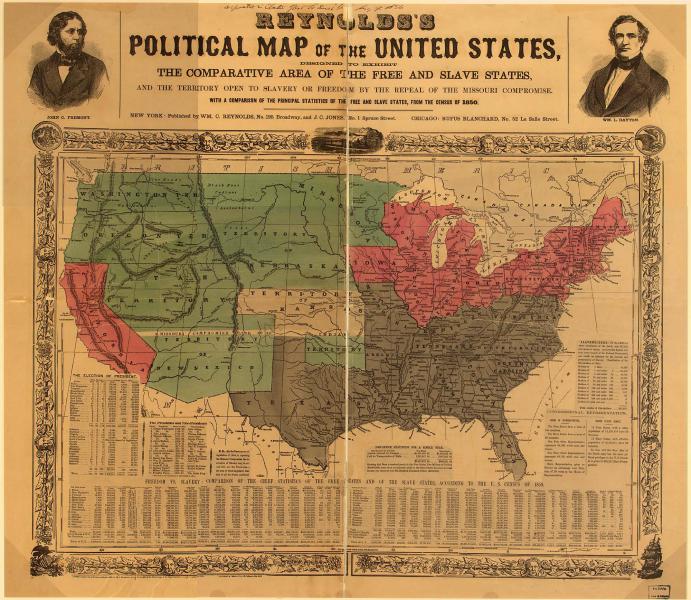

The victory over Mexico triggered yet another slavery crisis as President Polk worked to have Texas admitted to the Union as a slave state. Once again the threat of secession loomed. This time the conflict was resolved by the introduction of the Compromise of 1850. While offering compromise on the admission of Texas as a slave state, the law held to the line established by the Missouri Compromise of 1820 that banned slavery north of the 36°30' parallel. It also introduced “popular sovereignty,” albeit on a limited basis, allowing Utah and New Mexico to decide for themselves whether to be slave or free upon admission to the Union as states. After much political maneuvering by Senator Stephen A. Douglas, the bill passed with Pierce’s support. The compromise allowed the nation to step back from the brink of dissolution, but it laid the foundation for Pierce’s greatest challenge as president – a challenge that he would not meet effectively.

In 1852, the Democratic Party divided not just over slavery, but also over “internal improvements, temperance, nativism and the perennial disputes over patronage,” and it convened to select a candidate for the presidency. The primary contenders were Lewis Cass, James Buchanan, William L. Macy, and Stephen Douglas. Pierce emerged as the compromise candidate even though he had been out of mainstream national politics for some time. A true “dark horse,” he did not receive a single vote in the first ballot. By the 49th ballot, the little-known Pierce was declared the winner and the Democrats’ choice to challenge Whig Party candidate Winfield Scott and Free-Soiler John P. Hale in the presidential election.

Winning both the popular and the electoral vote, Pierce assumed the presidency on March 4, 1853. Although the Compromise of 1850 temporarily suppressed the tension over the expansion of slavery, political conflict resurfaced when Secretary of State William Marcy drafted a proposal to purchase Cuba from Spain or take it by force if Spain refused to sell. Northerners and abolitionists saw the Ostend Manifesto (as the document became known) as a blatant attempt to introduce another slave state into the Union.

The uproar over the Manifesto paled to that which erupted over the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854. Initiated by Stephen A. Douglas as part of his plan to develop a transcontinental railroad, the act nullified the Missouri Compromise of 1820. The law allowed all new states, including those states north of the 36°30' parallel, to use popular sovereignty to decide the status of slavery on their admittance to the Union. Even as the bill was being debated, proslavery and antislavery advocates rushed to Kansas and Nebraska territories to establish residency and influence the vote for their cause.

Pierce claimed to abhor slavery, yet he supported the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the Southerners’ position as to their constitutional right to expand slavery into the territories. When proslavery advocates in Kansas established a territorial government using fraudulent means, Pierce officially recognized it. He then expressed outrage when antislavery settlers attempted to oust the government by voting in one of their own. Violence between the two factions raged, and “Bleeding Kansas” became the cause d’ célèbre for antislavery supporters in the North. This period of civil unrest is seen by many historians as the true beginning of the Civil War. The violence polarized the two sides to the point that compromise seemed impossible. Pierce was unable to effectively restore even the uneasy peace that existed before his election.

The conflict over the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the atrocities committed by both sides deepened the North-South divisions. In a congressional report, Howard H. Reader wrote, “this Kansas matter . . . [has] given him more harassing anxiety than anything that had happened since the loss of his son; it haunted him day and night, and was the great overshadowing trouble of his administration.” Pierce lost his reelection bid to another Democrat, James Buchanan, whose every attempt to placate the South also failed. Four years later, the Southern states saw the election of Abraham Lincoln as the final Northern betrayal and began seceding from the Union. On April 12, 1861, General P.G.T Beauregard of the Confederate Army fired on Fort Sumter and the Civil War began.

Although Franlkin Pierce supported a defensive war, he opposed the “aggressive war of conquest” that he believed Lincoln was waging. As a strict constitutionalist, he was also openly critical of Lincoln’s decisions to suspend habeas corpus. According to historian Peter Wellner, Pierce’s position was that “only Congress may suspend the writ of habeas corpus,” and he supported “Chief Justice Taney's ruling to this effect . . . in Ex parte Merryman.” When Lincoln ignored the ruling and continued to hold Lt. John Merryman in prison, Pierce “deplored the excuse of ‘state necessity’ to justify such expansion of power.” True to his belief in the Southern cause, he blamed the abolitionist for the war. When letters to his friend Jefferson Davis expressing this view and his lack of enthusiasm for the war effort were uncovered and published, his reputation was permanently damaged.

While Franklin Pierce tried to keep the Union together, his policies laid the foundation for the very conflict he tried to avoid.Franklin Pierce died in Concord, New Hampshire on October 8, 1869. He was buried next to his wife and two of his three children in Old North Cemetery. Despite his long service to his state and his country, Franklin Pierce is judged harshly by some as a man on the wrong side of history. More recent scholarship accords Pierce credit as a good citizen and a moderate with, as described by historian Peter A. Wallner, “consistent legal and ethical conduct [who] kept the nation on a course of prosperity and growth,” and whose administration “was the best the nation could have hoped for at the time.” Nonetheless, while Franklin Pierce tried to keep the Union together, his policies laid the foundation for the very conflict he tried to avoid.

Suggested Reading:

Foner, Eric. Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

The University of Virginia Miller Center. American President Reference Center. "American President: Franklin Pierce (1804–1869)."

Wallner, Peter A. Franklin Pierce: Martyr for the Union. Concord, NH: Plaidswede Publishing, 2007.

Cite This Page:

Keating, Deborah. "Pierce, Franklin" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Thursday, April 18, 2024 - 22:18 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/pierce-franklin