By John Horner, Kansas City Public Library

In 1855 members of the Wattles family first settled in Kansas in response to the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which allowed territorial settlers to elect legislatures that would determine whether the territory would enter the Union as a free or slave state. The Wattles family came to Kansas with intentions of swaying these referendums toward the Free-State cause. Once they arrived, the family participated in Free-State Party politics, helped found the town of Moneka, edited an antislavery newspaper, connected with the radical abolitionist John Brown, and even advocated with some degree of success for women’s suffrage in Kansas.

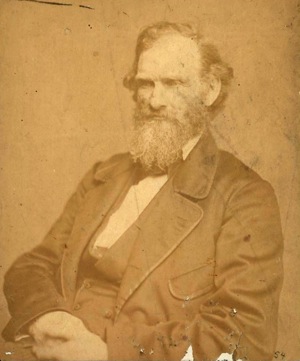

Augustus and Susan Wattles

Born in 1807, Augustus Wattles attended the Oneida Institute in Whitesboro, New York (a village located in Whitestown). He then moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1833 to attend the Lane Theological Seminary, which, for many of the students had become a center of the abolitionist movement. In Cincinnati, Augustus eventually dropped his studies at Lane and started a school for freed and escaped slaves, also working with the Underground Railroad to move escaped slaves to Canada. Two years after moving to Cincinnati, he brought his future wife, Susan Lowe, from New York to teach at the school. They raised money to purchase a substantial amount of land and established a settlement of small farms for the freed slaves, as well as a school for boys.

After marrying on June 24, 1836, Augustus worked as an agent for the American Antislavery Society, traveling great distances to raise money and speak on behalf of abolition. Following passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, he and Susan moved their family to Kansas in early 1855 to fight for the Free-State cause. Within a few months he ran twice for a seat in the legislature and received a certificate of election from Governor Andrew Reeder, but the proslavery “Bogus Legislature” denied his seat when he arrived at the first territorial capitol near Fort Riley. He was also elected as a delegate to the antislavery Topeka Constitutional Convention.

Augustus, Susan, and their four children staked out a farm in Douglas County, and he wrote articles for the Herald of Freedom newspaper, which was published in the Free-State town of Lawrence, Kansas. He eventually became George W. Brown’s assistant editor for the paper. When a proslavery posse imprisoned Brown in the Sacking of Lawrence for his strong advocacy of Free-State objectives, Wattles became the de facto editor. Throughout most of 1857, he wrote a series of weekly articles for the paper under the title, “Complete History of Kansas.” In these articles, he challenged the concept of “squatter sovereignty,” by which “a few settlers who might first inhabit a territory, could establish its present and future domestic and political institutions.” He pointed out that men from Missouri, known as “border ruffians,” made a trip to Kansas in June 1854 to hold a squatter meeting, pass resolutions, and then go back home. He wrote, “Every fair arrangement for a free government was rejected, and all was left in the hands of those who expected to make [Kansas] a slave state.”

Even with raids and the Sacking of Lawrence by proslavery partisans, Douglas County was strongly in the hands of Free-State advocates. Places like Linn County, though, fell into the hands of the proponents of slavery, who had driven Free-State settlers out. In February 1857, Augustus became one of the founders of Moneka, Kansas, to the northwest of present-day Mound City in the central-eastern part of the state. That winter the founders, including Augustus and his brother, John O. Wattles, moved there.

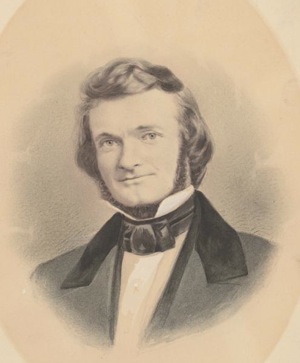

John O. Wattles

John Wattles, born two years after Augustus in Goshen, Connecticut, eventually followed his brother to Cincinnati, working with him for two years after Augustus had started his school for blacks. In 1838, John began working as a tutor for the family of James C. Ludlow, past president of the Ohio Antislavery Society, and financial backer of the Philanthropist, a prominent abolitionist journal.

John married Esther Whinery in 1844. During the first several years of their marriage they lived in a series of failed communal settlements in Ohio and Indiana, where John remained involved in antislavery activities, including the Underground Railroad.

When John followed his brother, Augustus, to Kansas in 1857, he chose not to settle with him in Douglas County. John instead settled in Linn County, where Augustus followed just over a year later, and the two brothers laid out Moneka. John constructed a large building for an academy, and over the next two years he put in a great deal of time toward establishing a railroad between Emporia, Kansas, and Jefferson City, Missouri (not coincidentally running through Moneka). He successfully lobbied Congress for the land grant and right of way. His sudden death on September 20, 1859, and the abrupt loss of the railroad’s chief proponent, caused the project to falter and fail.

The Wattles Family and John Brown

The radical abolitionist John Brown was friends with both Wattles brothers, most specifically with Augustus. While they agreed with Brown’s goals, they often disagreed with his methods. Whereas Brown was convinced that slavery would be ended only through violence, Augustus sought to attack it by swaying people’s minds. In December 1858, however, when Brown needed a place to stay after a Missouri slaveholder was killed during Brown’s raid into Missouri to free 11 slaves, Augustus offered sanctuary at his own home in Moneka, even though the Missouri governor, Robert M. Stewart, insisted that Brown and the slaves be returned to Missouri.

During his stay with the Wattles family, Brown wrote a letter he sent to the Lawrence Republican, comparing his raid into Missouri with the Marais des Cygnes Massacre, in which a raiding party from Missouri had crossed into Kansas and, near a settlement called Trading Post, killed five men suspected of being antislavery supporters, while badly injuring five others. Wanting to protect the Wattles family from any retribution that would have followed had the proslavery element known that Augustus had provided sanctuary to him, Brown indicated that he was writing, not from Moneka, but from Trading Post.

During the last days before his execution nearly a year later, Brown, in one of his final letters to his wife, referred to the Wattles family as,

most beloved and never to be forgotten by me. Many and many a time has she [Sarah Wattles], her father, mother, brothers, sisters, uncle and aunt, (like angels of mercy) ministered to the wants of myself and of my poor sons, both in sickness and in health.

After Brown was executed for his raid on Harpers Ferry, Congress subpoenaed Augustus to travel back to Washington, D.C., to answer questions regarding any knowledge he had about Brown’s raid. Once there, Augustus denied knowing anything about Brown’s plan before the attack.

Women’s Suffrage

The entire Kansas contingent of the Wattles family saw continuity in the need for change on a wide range of social issues, which led them to found the Moneka Women’s Right’s Association and advocate for women’s suffrage. As Susan Wattles wrote to Susan B. Anthony in 1881, “the first in the woman suffrage cause [in Kansas] were those who had been the most earnest workers for freedom. They had come to Kansas to prevent its being made a slave State.”

The Moneka Women’s Rights Association traced its origins to a meeting held on February 2, 1858, after one of John Wattles’s lectures on women’s rights, where, as noted on page two of the Secretary’s Book of The Moneka Womans Rights Association, “a proposition was made to organize a Women’s Rights Society.” This became the Moneka Women’s Rights Association, which included both women and men as members. On February 13, according to the Secretary’s Book for the group, the Association elected John’s wife, Esther, vice president and Susan’s and Augustus’s daughter, Sarah Grimké Wattles, secretary.

Sarah Grimké Wattles was named after the abolitionist and suffragist, Sarah Grimké, with whom her mother corresponded (besides Grimké and Anthony, Susan’s other correspondents included Clarina I.H. Nichols and Elizabeth Cady Stanton). Sarah had not been with her family when they had first moved to Kansas, but she led her sisters in taking a hatchet to a tavern some 28 years before Carrie Nation. She was an officer in the Moneka Women’s Rights Association and a property owner in Kansas. She even learned medicine from her husband, Dr. Lundy Hiatt, and the pair set up a joint practice in Texas. When he died in 1892, she split her time between Texas and Kansas, continuing her work for women’s rights until her death in 1910.

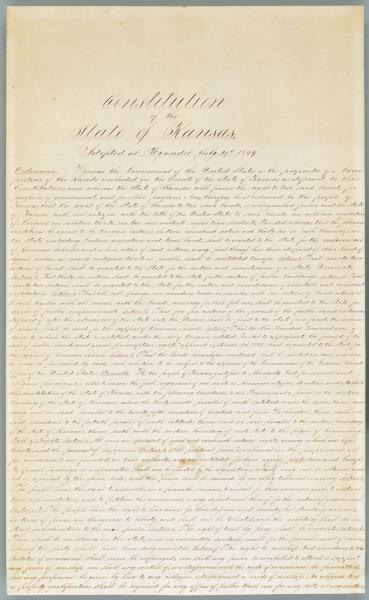

In Kansas, the Wattles family contributed to modest but still noteworthy progress in women’s rights. Rights included in Kansas’s “Wyandotte Constitution” allowed women equal rights for child custody in divorces, property rights, and consequent with the phrase “equality in all school matters,” women were able to attend the University of Kansas from the school’s founding, making it one of the first publicly funded coeducational colleges in the nation. The constitution also asserted the right of women to vote in school board elections, although in the early years this last right was often simply ignored by local authorities.

Epilogue

John Wattles died suddenly in September 1859, and after the Civil War, his wife Esther returned to Oberlin, Ohio, with her three daughters (and her niece Mary), where she kept a boarding house. Her daughters and niece all graduated from Oberlin College, and Celestia became a professor of music. Her sister Harmonia served as dean of women. In later years Esther moved to Coconut Grove, Florida, to live with Harmonia and died in 1908.

With the Emancipation Proclamation, Augustus focused on working with newly freed slaves, helping them make the transition from slave to citizen. He died at the age of 69 in Mound City, Kansas, on December 19, 1876.

Augustus’s wife Susan remained in Mound City, living just over 20 years longer. She remained active, continuing her correspondence on behalf of the rights of women and seeing many strides in women’s equality. She died in Mound City on January 9, 1897.

The influence of the Wattles family in the Civil War period long outlived the individual members of the family who struggled for the end of slavery and on behalf of women’s rights and temperance.

Suggested Reading:

Earle, Jonathan and Diane Mutti Burke, eds. Bleeding Kansas, Bleeding Missouri: The Long Civil War on the Border. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2013.

Eickhoff, Diane. Revolutionary Heart: The Life of Clarina Nichols and the Pioneering Crusade for Women's Rights. Kansas City, Kansas: Quindaro Press, 2006.

Getz, Lynne Marie. “Partners in Motion: Gender, Migration, and Reform in Antebellum Ohio and Kansas.” Frontiers. Vol. 27, No. 2 (2006): 102-135.

Kansas Historical Society. “George Washington Brown.” January 2010, modified March 2013.

Kansas Historical Society. “Moneka Woman's Rights Association.” January 2010, modified March 2013.

Oertel, Kristen Tegtmeier. Bleeding Borders: Race, Gender, and Violence in Pre–Civil War Kansas. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2009.

Robertson, Stacey M. Hearts Beating for Liberty: Women Abolitionists in the Old Northwest. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Cite This Page:

Horner, John. "Wattles Family" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Friday, April 26, 2024 - 02:02 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/wattles-family