By Christopher Phillips, University of Cincinnati

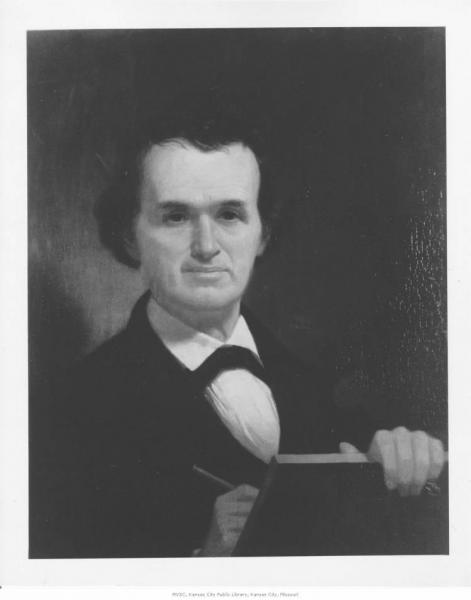

In February 1862, the Missouri provisional government’s new state treasurer, George Caleb Bingham, saw a troublesome development in his war-torn state. Garrisoning federal troops, especially in the western portion of Missouri, were subjecting civilians "to a kind of winnowing process by which the 'tares' were to be separated from the wheat — the loyal from the disloyal portion of the inhabitants."

The statement of a single individual . . . was to be taken as conclusive [and] it was not, for a moment, deemed necessary, that any investigation, in form, should take place. . . . [before they] drew a line, sufficiently legible, between Unionists and Secessionists.

With an artist’s eye for detail, Bingham’s “winnowing” was in fact a reference to measures implemented by the federal military to accomplish sharp categorizations among a deeply divided populace in an ostensibly loyal state, many of whom claimed themselves neutral in the contest.

The Dominion System

The American Civil War, especially in border slave states like Missouri, prompted hardened, albeit sometimes erratic, definitions of loyalty and disloyalty from a population with a wide array of political stances. In 1861 and 1862, border state citizens like Bingham witnessed the development of a dominion system – an integrated, if imperfectly implemented, knot of counterinsurgency measures conducted mostly by low-level, often volunteer post commanders and assisted by civilian informants. They included:

- Military districting and garrisons;

- Oaths and lists of civilians categorized as “loyal” and “disloyal;”

- Civilian assessments, or levies;

- Martial law, or the suspension of civil authority in favor of military rule;

- Provost marshal system, or the use of military personnel to preserve order among civilians, along with other functions, during the war (began informally in Missouri and other border states in 1861);

- Trade restrictions and the permit system, which allowed military personnel and civilian boards to regulate which civilians engaged in legal commercial activity.

With Abraham Lincoln’s assent, military leaders at the local level implemented these measures as a broader strategy to establish control of the “chaos of incendiary elements,” as one commander referred to the often armed local populations, whose true loyalties were often uncertain and changing. This contest for definitions in fact allowed little room for neutrality, as citizens were caught in the web of restraints that aligned along the binary of loyalty and disloyalty. The outcome directly affected societal harmony and authority in Missouri and all of the border states for the duration of the war.

Soldiers performed professionally under the best of circumstances, but overzealously or even murderously under the worst.Administering the dominion system required interaction between federal troops, militia or home guard, and unionist citizens. Garrisoning towns, especially small ones, often required the commandeering of the communities’ physical structures and private homes for the army’s use. Damage or destruction often followed, as did the confiscation of private property.

Once the garrisoning of local towns was accomplished, ferreting out and suppressing perceived disloyalists—their primary task—required search patrols of varying sizes. Soldiers performed professionally under the best of circumstances, but overzealously or even murderously under the worst. In either case, cavalry patrols regularly roamed the countryside on self-styled “scouts” looking for disloyalists, saboteurs, and guerrillas.

However patriotic the motives of soldiers and officers, many had arrived in Missouri from free states with preconceived notions of its propertied inhabitants as wealthy, proslavery, disloyal southerners. Distinctions between loyal and disloyal property owners often evaporated in the minds of the occupying troops. Many soldiers evinced distrust or disdain for the mass of residents, especially slaveholders. One cavalry officer, Wyllis C. Ransom, an abolitionist hard-liner who had recently moved to Kansas from Wisconsin, concluded that the broadest portion of the border populace was disloyal.

“At the outbreak of the war,” Ransom recalled,

The people of the rural districts of the western part of the state of Missouri were divided into three classes—The first comprising one quarter were loyal to the United States but for the most part, of necessity, secretly so, and were soon compelled to join the Union armies or to seek the protection of Union communities. Another quarter were open in their hostility to the government, and showing their faith by their work, were soon found with [James] Rains or Price in the armies of the Confederacy. The remaining half were secretly hostile to the United States through professedly friends, non-combatants or neutrals. It was from the last class that the cruel wars of Missouri were mostly realized.

Not surprisingly, Ransom’s 6th Kansas Cavalry was the subject of numerous complaints lodged by western Missourians of theft and wanton destruction.

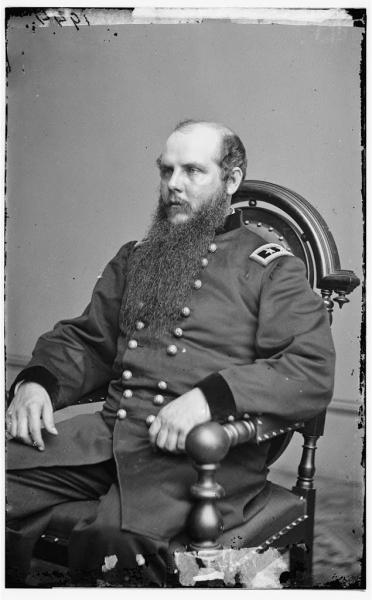

In the fall of 1863, Brigadier General John McNeil, a Canadian-born, St. Louis Yankee notorious for his role in the “Palmyra Massacre” the previous year, included a stern dictum on qualified loyalty in a general order he issued in southwestern Missouri. “The citizen who has chosen the position of neutrality and who claims or has claimed to have ‘done nothing on nary side,’ is not loyal.”

Many Union troops soon confronted personal disputes, feuds, slights, and political differences that, after festering for years prior to the war, quickly broke open. Major General John M. Schofield complained that the war in Missouri was largely “the result of old feuds, and involves very little, if at all, the question of Union or disunion.” Open conflict offered what one local called an “evening-up time . . . [when] many a man became a violent Unionist because the ancient enemies of his house were Southern sympathizers.” Class resentments certainly drove many such complaints against prominent landowners. Slaveholders in particular were targets. As one Missourian of moderate means later sneered, “the cry of ‘disloyal’ could be very easily raised against any man who happened to have a superabundance of property.”

Local Unionists’ targeting of prominent residents figured into federal troops’ rejection of nuanced political stances. Widespread military arrests, often made “on the slightest and most trivial grounds” (including for simply writing to those in the Confederate army or states), occurred throughout the border slave states. Without oversight, prisoners jammed courthouse jails and other sites of confinement, “arrested without any cause, except that they were reported secessionists,” as one St. Louis resident reported.

Prisoners jammed courthouse jails and other sites of confinement, “arrested without any cause, except that they were reported secessionists."

The historian Mark E. Neely, closely examining the federal government’s arrest records during the war, has concluded that some 13,000 civilians were arrested throughout the nation, the largest portion of whom were in the border states. His figures do not even include Missouri, where fragmentary evidence suggests a “formidable if not staggering” number of civilians likely were detained. Indeed, in excess of 2,000 were incarcerated at St. Louis’s Gratiot Street prison alone from April 1862 to October 1863. Neely also acknowledges that poor record-keeping would likely ratchet up any such estimate in Missouri.

Home guard and state militia members who supported or replaced the garrisoning troops were contributors to this shadow war. A resident of Elk Fork, Missouri, complained that his local home guard “came from all parts of the County and Some of them have little grudges at their fellow Citizens and they make use of their opportunity to avenge themselves.” Lincoln himself heard complaints that “arrests, banishments, and assessments are made more for private malice, revenge, and pecuniary interest than for the public good.”

The abuses by both federals and Confederates, militia and home guard were pronounced enough for John C. Frémont and Sterling Price, leading “antagonist forces” in the field in November 1861, to issue an unusual joint proclamation. It pledged that “future arrests or forcible interference by armed or unarmed parties of citizens . . . for the mere entertainment or expression of political opinions shall hereafter cease . . . and that the war now progressing shall be exclusively confined to armies in the field.” Six weeks later, Major General Henry Halleck pledged to disband home guard units in Missouri, “as rapidly as I can supply their places” with state militia.

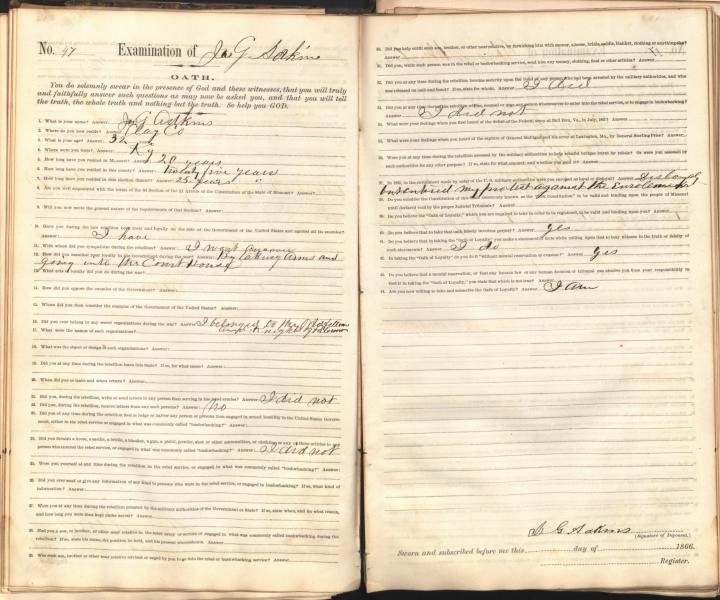

Oaths of Allegiance

Following on the heels of these widespread arrests, formalized oaths of allegiance became the most ubiquitous symbols of federal authority. The widespread assumption that disloyal majorities of secessionists and neutralists were cowing loyalists in the border states made oaths virtual tools of the occupying troops. Even many unionists objected to being forced to take the federal oath, but others saw some utility to the oaths. One soldier wrote home to his aunt that when administering the oath, “It just sutes me to hear them grumble.” But unionists’ objections surprised him. “It dont hurt a union man to take the Oath,” he admitted, “but we find once in a while one that hates to take the Oath but durst not say anything Once in a grate while they are catched by some of us that over hear their conversation and then put them under an arrest.”

Many citizens who took the oath did so duplicitously. One woman spat that “every one has been required to take the oath—they are then called Loyal—What a mockery.” Others refused entirely. The oath supporting the provisional government, enacted in December 1861 and required of public officials, was especially reviled because many condemned the convention as extralegal. They claimed that they had taken one already when assuming their positions, and taking the “convention oath” suggested their disloyalty.

This was, of course, exactly the point. Their refusal to cooperate implied the rejection of the legitimacy either of the state or federal governments. Residents’ refusal to take either the federal or state oath smoked them out, as it were, especially with the final words: “SO HELP ME GOD.” One southeast Missourian knew well that many of his neighbors feigned neutrality, and taking the oath would unmask their ideological beliefs. “They believe this war is waged against slavery,” wrote Joseph C. Maple, who nevertheless condemned “the Republican mode of carrying on war. . . . Hence they do not wish to take an oath which will cut them off from giving aid to the South.”

The oath sharpened these blurred lines to the great advantage to the government, as one Missourian saw it. “The doubtful men, thinking they were getting to the strong side, [are] joining the rebels, but I believe we are really better off having them avowed against us than as pretended neutrals.” Those so exposed were arrested, publicly listed, and required to post bond in order to gain their release, with sureties (from a few hundred dollars to many thousands) and the affidavits of Unionists who guaranteed their future good behavior. In 1862 in the Liberty, Missouri, district, near the Kansas border, provost marshals required 612 persons to post bonds totaling some $840,000. The provost marshal in Palmyra, near the Mississippi River, reported taking in as much as one million dollars that year.

However unpopular they were, oaths and bonds had an obvious practical value. Identifying secessionists was a challenge, perhaps the challenge for federal authorities. Lists of those who took or refused the oaths were essential identification tools for federal commanders in local areas. Their reliance on oaths and lists to suppress local disloyalists, who were spread throughout their districts, stemmed in part from vulnerability. The small, town-based garrisons were hard-pressed to keep order so far from the army.

Taking or Forsaking the Oaths

Local residents who took the oath disingenuously believed doing so kept their true loyalties hidden. A resident wrote that some of the residents around him “say that they did not mind taking the oath as they did not consider it binding on them, in fact they would rather take the oath than not as it gives them protection and they can get passes to go where they please.” As such, department commanders and provost marshals routinely required accompanying verification of letter writers’ own loyalty in order to solicit a response to their claims or grievances. Mistakes occurred frequently, eliciting remonstrances that required commanders to discern the legitimacy of the listed names and whether the information they had received on such individuals was politically contrived.

Taking the oath presented a crisis of both honor and conscience for many citizens, even neutralists. It was the most visible symbol of personal coercion. For many white Missourians, these oaths were at best superfluous, as they were already residents of a loyal state, and at worst unconstitutional for assuming guilt before innocence and abrogating First Amendment rights. They resented that local commanders and provost marshals forced the oaths on residents who did nothing more than speak out against the military occupation or in favor of Southern rights. “There are a number of influential citizens in this vicinity of rebel proclivities,” wrote one cavalry colonel, “who although they have not committed any overt act . . . in conversation they have defended the cause of the South in a very noisy and offensive manner.”

Unionists, government troops, and the home guard used the oath against neutralists, Southern sympathizers, and secessionists who refused to take it.

Despite capricious and even corrupt determinations of loyalty and disloyalty, Lincoln left to department commanders the discretion to make such decisions, recognizing that this was the single most critical point with which to keep order in the border states. As the president wrote his department commander in Missouri, assessing the loyalty of residents “must be left to you who are on the spot.”

Oaths visibly divided local communities. Civilians who took the oath or posted bond, or both, often found themselves exposed. Visitors known to be disloyal often attracted the attention of armed federals. One bonded Missourian wrote in October 1862, after sending away one such visitor, “I was fearful that some of the Negroes about the house might see him. The danger was greater to us than to him. He saw that he was an unwelcome visitor, and left as abruptly as he came.”

Reprisals often followed, resulting in societal divisions that in some cases worked to the government’s advantage. Unionists, government troops, and the home guard used the oath against neutralists, Southern sympathizers, and secessionists who refused to take it. Yet disloyal residents often chastised those neighbors who did take it, whether feigned or not, as cowards or disloyal to the Southern Cause.

Shunning was only the most benign form of retribution made against oath-takers. Many others were insulted, threatened, and even attacked for their capitulation to Yankee aggression. Worse, they were turned in to garrison commanders as disloyalists. In July 1862, Miami, Missouri, merchant John Scott found himself arrested for disloyalty by armed state militia with guns pointed, only to learn after his bonded release that a neighbor, “one of the most violent and uncompromising secessionists, intolerant to Union men, getting ready to go to the Southern army and having [secession] flags on house and business building,” had reported him following a private disagreement between them.

Complaints from prominent unionists about the occupiers’ strident measures were plentiful, questioning their severity, capriciousness, and especially corruption. Most important, the federals’ presence seemed to many to be fueling the insurgency in Missouri. Reverend William G. Eliot, a prominent St. Louis Unionist, nonetheless questioned the ability of the military to “assort and classify these, so as to indicate the dividing line of loyalty and disloyalty . . . is a task of great difficulty.” He saw only harm to the public weal. “The bitterness of feeling,” wrote the concerned clergyman, “will renew the personal hostilities which were beginning to disappear, and, thus fanned, the secession element will refuse to die.”

View a video clip of Pulitzer Prize winner Mark E. Neely, Jr. discussing Lincoln's interpretation of the Constitution at the Kansas City Public Library.

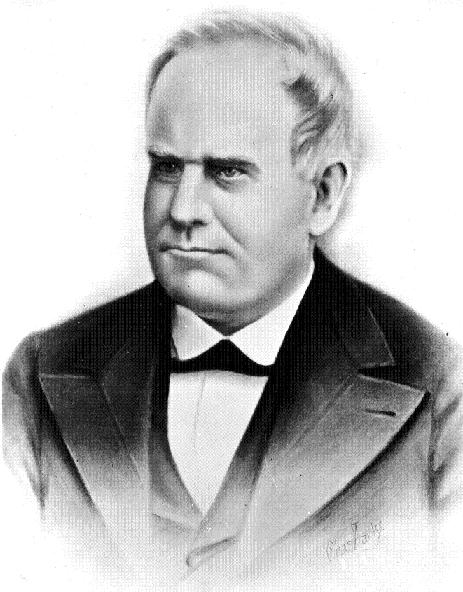

On August 25, 1863, in the aftermath of William Quantrill’s brutal guerrilla raid on Lawrence, Kansas, the centrality of definitions of loyalty and disloyalty in Missouri would eclipse all other locales during the Civil War. Recognizing the unreliability of hitherto differentiations between the loyal and disloyal, Brigadier General Thomas Ewing, commanding the District of the Border, issued General Order No. 11. The orders required nearly all residents of four of Missouri’s western border counties (Cass and Bates counties, virtually all of Jackson, and the northern half of Vernon County), living more than a mile from the four military posts in the area, to come to those posts to be certified as loyal by military authorities.

What resulted was the national government’s first-ever forcible removal of white, propertied citizens from their homes. Of the some 40,000 people who had inhabited the area at the start of the war, whether unionist or not, none could stay in their homes. As one newspaper reported, anyone who remained “not within the protection of a Military Station . . . and is not molested is [seen as] a rebel or rebel sympathizer.” The resulting population displacement and destruction of property (lest it fall into rebel hands) prompted the nickname “Burnt District,” as an apt description of the region.

In early 1862, even before Order No. 11 took the dominion system to new extremes, Missouri’s provost marshal general, Bernard G. Farrar, wrote from his headquarters in St. Louis, “It is now purely a question of power not one of law. ” At nearly the same time, that state’s lieutenant governor, Willard P. Hall, spoke similarly to conditions in his state. “Amidst armies,” he asserted, “the law is silent.” Both men’s candid views of the authority of an occupying army among an increasingly hostile citizenry were placed, curiously, within the context of instructions to desist in arresting civilians around the state merely on suspicion of disloyalty. But their views precisely defined the circumstances in Missouri and other border slave states, where martial authority and civil laws grappled for supremacy, plunging civilians deep into the shadow world of war.

Suggested Reading:

Ash, Stephen V. When the Yankees Came: Conflict and Chaos in the Occupied South, 1861-1865. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

Fellman, Michael. Inside War: The Guerrilla Conflict in Missouri During the Civil War. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Neely, Mark E., Jr. The Fate of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln and Civil Liberties. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Cite This Page:

Phillips, Christopher. "Shadow War: Federal Military Authority and Loyalty Oaths in Civil War Missouri" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Saturday, April 27, 2024 - 09:46 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/essay/shadow-war-federal-military...

Rights/Licensing:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License