By T.J. Stiles,

If you look at any national map of the Civil War, you will see no contrast between Kansas and Missouri. Both are shaded alike as Union states. Were we to map the memory of the war, on the other hand, the border between them would be bright and stark. Kansas would still be Northern. But much of western Missouri would go with the South.

The war’s legacy in Missouri’s borderlands presents something of a mystery. Consider the example of Harry S. Truman and Dwight D. Eisenhower. They had a lot in common. They served consecutive terms as president. They grew up only 160 miles apart in the late-19th century – Truman in Independence, Missouri, and Eisenhower in Abilene, Kansas. Local history mattered to both of them. Yet very different versions of the past lived in their imaginations.

Divergent Views

Truman was steeped in the Civil War - in particular, his own family’s suffering at the hands of jayhawkers.

Eisenhower grew up with Wild West lore: cattle drives, cowboys, and the man he called “our marshal,” Wild Bill Hickok. Just over the border, Truman was steeped in the Civil War - in particular, his own family’s suffering at the hands of jayhawkers. When he came home from his first trip to Kansas, his mother asked if he had found his grandmother’s silver, supposedly stolen by Kansans wearing Union army blue.

These tales were more closely linked than either man might have realized. Hickok had fought for the Union in Missouri. His first town-square man-to-man gunfight took place in 1865, in Springfield, Missouri, against former Confederate Dave Tutt. And Truman built his political career in Kansas City, a town that grew in prominence after the Civil War and became closely linked to the Kansas economy.

If Kansas and Missouri were intertwined, why was the Civil War central to Truman’s identity, but not Eisenhower’s? If both were Union states, why did Truman see himself as a Southerner, while Eisenhower considered himself a Westerner?

Missouri’s guerrilla conflict tore the state apart. Neighbors fought neighbors and then struggled for dominance afterward.

The legacy of the Civil War diverged because Missouri experienced the conflict—and its aftermath—quite differently than did Kansas or indeed most Union states. After the “Bleeding Kansas” conflict ended, Kansas enjoyed relative unity. Its soldiers mostly went off to fight rebels in Missouri or distant theaters. When the armies demobilized, Kansans returned from afar, and the state’s attention turned to new things, especially westward expansion.

But Missouri’s guerrilla conflict tore the state apart. Neighbors fought neighbors and then struggled for dominance afterward. The key to postwar power was memory and identity. In the Civil War’s long shadow, a few mythmakers on the western border worked to convince Missourians that they lived in the South.

The War that Wouldn’t End

On April 12, 1865, three days after General Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House, the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia disbanded. That day, Sarah Harlan composed a letter in Haynesville, Clinton County, in western Missouri. “We hear great talk of peace,” she wrote, “but the bushwhackers are plenty.”

Two weeks later, Union General Clinton B. Fisk wrote to a Platte County politician, “Organize! Organize! All volunteer troops are being withdrawn from North Missouri; martial law will soon be abrogated; civil law will be supreme. Spencer rifles must aid in the good work.”

Harlan and Fisk feared that violence would rage on in western Missouri, and for good reason. Combatants on each side were from the same communities. The front line had often been the threshold of the front door. With “peace,” Confederate guerrillas did not demobilize—they came out of hiding. Fear of retribution hung in the air.

One sign of the war’s intensity is the fact that some Confederates refused to admit it was over. On May 11, more than a month after Appomattox, guerrilla Archie Clement actually demanded the surrender of the town of Lexington, in Missouri’s Lafayette County. As the Confederacy’s collapse struck home, the bushwhackers debated their course of action and finally broke into two parties. The larger group, led by Dave Pool, surrendered peacefully. The other, led by Clement, remained at large, armed, defiant, and very dangerous.

A Land of Bitterness

Clement was not the only angry Missourian. The guerrilla war had inflicted widespread suffering on civilians; it upended the border region’s economy and society. Even in peace, turmoil prevailed.

“Most all of the families that used to live here moved away,” Amanda Savery wrote to her husband in 1865, from Liberty, Clay County: “The Eatons are all banished and many others.... There has been a great many deaths among your friends.” Families exiled under martial law took months to return, if they did at all. The Samuels of Clay County—family of guerrillas Frank and Jesse James—did not come home until August 1865.

Emancipation was the war’s moral triumph, but it angered former slaveholders, who lost much of their “property.” By contrast, it had little impact on Kansas, where few were enslaved when the war began. Western Missouri’s labor force also declined as the freed people fled, even before slavery was abolished in the state. For example, Clay County’s black population fell by half from 1860 to 1864.

Citing "unpaid taxes," the Unionist authorities in Missouri auctioned off numerous farms of those who had gone to fight for the South. Often buyers came from outside the state - though few from the South.

Victims and perpetrators often knew each other. "Peace" meant an opportunity to get even.

Bank failures also reduced the economic power of the old elite, the large slaveholders of the Missouri River Valley. In 1861, these men had used the banks to arm local Confederate recruits through a kind of check-kiting scheme. They counted on repayment from the victorious Confederacy. Instead, the banks folded and were bought by Unionists.

Finally, there was the hunger for revenge. The war had been brutal: ambushes with short-range pistols, torture, summary executions, house- and farm-burning. Victims and perpetrators often knew each other. “Peace” meant an opportunity to get even.

Amanda Savery wrote to her husband on July 1, 1865, that returning Southern fighters “were shot as fast as they came, as civil war is in force.” Five months later, Jackson County bushwhacker Bill Runnells called out two Unionists and killed them. On June 15, 1866, Lass Easton ran into guerrilla Jim Green in a grocery store in Clinton County. Easton accused Green of helping to burn his father’s house; Green shot him dead. Sarah Harlan wrote, “One of Easton’s brothers says he intends to kill Jim if he follows him to the end of the world.”

As late as October 1866, army Lieutenant James Burbank investigated reports of “an armed pistol company” in St. Clair County. It was like searching for a needle in a needle factory. “Nearly every man I saw . . . carried army revolvers, even men at work in their fields, and boys riding about town,” he reported. He called it “a habit which grew out of the unsettled condition of the country since the war.”

The New Order

For all of the tensions, secessionists remained a distinct minority in Missouri. So how did a Southern identity emerge on the western border? How did the state’s internal war come to be remembered as a battle against outsiders?

Much of the answer lies in the collapse of wartime alliances. Even before the peace, Missouri Unionists broke into two camps, Radicals and Conservatives. These Radicals should not be confused with Radical Republicans in Congress. The local variety were driven by a desire to punish secessionists, not by humanitarianism toward the slaves. Radicals on the western border were particularly vociferous. They wanted to penalize their “traitor” neighbors, with whom they had traded atrocities; they wanted to keep the rebels out of power, forever. They embraced emancipation to eliminate secessionists’ economic strength.

Conservatives, by contrast, wanted to heal the state quickly. They liked Missouri the way it was, and were reluctant to free the slaves and grant them civil rights.

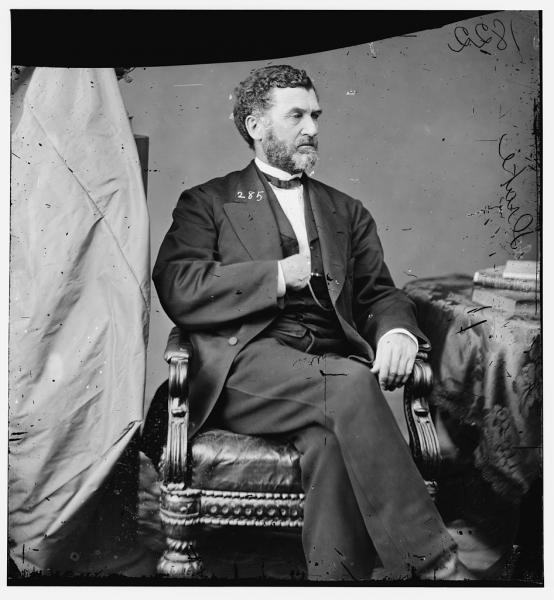

In 1864, the Radicals won the state election. Voters also approved a state convention on emancipation, which terminated slavery in January 1865. But the convention went further. Led by Charles D. Drake, an articulate, bullying Radical from St. Louis, it drafted a new state constitution, approved by voters on June 6, 1865.

Most of the “Drake Constitution” was unremarkable. But it imposed tight restrictions on secessionists - indeed, on anyone who could not take the Iron-Clad Oath. That oath was a declaration that one had not committed any of 86 acts, ranging from armed rebellion to expressing sympathy for an individual secessionist. Those who could not swear to it were barred from voting, running for office, sitting on juries, teaching, preaching the gospel, or serving as lawyers or corporate officers. County registration boards and supervisors—all Radicals—would have the power to bar anyone from voting whom they suspected of disloyalty.

Conservatives hated the new constitution. Politician William F. Switzler said it was written “in a spirit of malice and revenge.” Border Radicals felt otherwise. “I would rather today see a rebel with a musket in his hand than with a ballot,” wrote Robert T. Van Horn, the editor of the Kansas City Journal of Commerce, Union veteran, Kansas City mayor, and newly elected congressman. “If he outvotes me, I must take my musket and support the law or policy which he may impose.... Is Missouri never to have peace? Is treason to become a virtue and loyalty a crime?”

“I could see much bitterness and opposition expressed, one to the other, in the countenances of the citizens,” a traveler wrote, after visiting Lexington in early 1866. He quoted a resident on local politics. “We have here three papers, and three parties: —Democracy [i.e. Democrats], Radicalism, and Southern.” (At the time, Conservatives were taking the Democratic Party label, and Radicals the Republican, though the older terms continued to be used.)

Ironically, the Drake Constitution prepared the way for an alliance of Unionist Conservatives and secessionists. The heavy-handed use of the Iron-Clad Oath and openly partisan registration boards disfranchised even some loyal Democrats, who began to feel that they had much in common with their secessionist neighbors. In a grave political error, the Radicals essentially pushed their opponents together.

Election-Year Mayhem

Personal bitterness and political anger made a combustible mixture. In 1866, it exploded in a year-long firestorm. Violence first erupted in Liberty, at the Clay County Savings Association.

The fate of this bank shows how the war transformed western Missouri at the grassroots. Originally a branch of the Farmer’s Bank of Missouri, owned by wealthy slaveholders, it went bankrupt as part of the aforementioned secessionist fraud. It was taken over by Radical Unionists, many of whom were former militia officers and current public officials, sworn in under the Iron-Clad Oath.

On January 29, 1866, these men held a mass meeting of the Republican Party in Liberty. The first such rally in county history, it would have been inconceivable as recently as 1861. But the savagery of the war had radicalized the Unionists. They held power for now, but their enemies were armed and angry.

On February 13, 1866, exactly two weeks after this rally, the Savings Association suffered the first armed, daylight bank robbery during peacetime in American history. The bandits were bushwhackers led by Archie Clement, the guerrilla who had never surrendered.

Republican Governor Thomas C. Fletcher launched an offensive against the guerrilla outlaws, gathering intelligence and deploying sheriffs, posses, and militiamen. But his campaign played out against the backdrop of a bitter congressional election, which would decide the future of Reconstruction and, by extension, postwar America.

Republicans claimed there was no difference between secessionists and loyal Conservatives, who wanted leniency for the rebels. Radical mobs attacked or intimidated Democratic meetings and leaders. In this context, it was (and is) difficult to separate crime or law-enforcement actions from political violence—especially in the case of Clement and his gang.

On March 12, Governor Fletcher proclaimed a $300 reward for Clement’s capture. On March 13, he signed an emergency bill allowing him to call out the militia to aid county sheriffs, and ordered a general enrollment in the militia.

Local Republicans pleaded for army protection, writing, “Every Union man will be driven out of the county or murdered.”

But Clement’s gang struck again, mixing crime with political intimidation. They were suspected of more robberies. They harassed and threatened registration officials in Lafayette County. They ordered Radicals to leave Clay County, where more than 100 secessionists resisted the sheriff during an arrest. Local Republicans pleaded for army protection, writing, “Every Union man will be driven out of the county or murdered.”

Meanwhile Republican harassment of Democrats continued across western Missouri. It was said that a mob of 100 Radicals was driving Conservatives out of Daviess County; in Caldwell County, one man wrote, “There is a complete reign of terror” at the hands of Republican legislator Daniel Proctor. Rumors circulated that conservative ministers were gunned down in their pulpits.

"Have we not good reason to apprehend another civil war?” mused a secessionist in Missouri City. A Unionist Democrat could have written the same thing. Radical mobs, registration officials, and sweeps by posses and the militia made them feel that they were all targets of the Republican regime.

One militiaman heard Clement say, as he bled to death, “I’ve done what I always said I’d do - die before I’d surrender.”

The mayhem reached a climax on election day, when Clement and his men occupied Lexington. Democrats won as terrified Republicans hid. Having lost a major town to Confederate guerrillas a year and a half after the end of the Civil War, Governor Fletcher ordered in the militia. The state troops ambushed Clement, killing him in a running gunfight through the streets. One militiaman heard Clement say, as he bled to death, “I’ve done what I always said I’d do - die before I’d surrender.”

Radical Victory, Confederate Opportunity

Republicans won the state (and national) election. They sought to align Missouri with the North and embraced the influx of Yankees. “Which would you prefer,” asked one Republican, “to have Missouri filled with men from [the Confederate] armies, or with loyal men from Ohio, New York, and New England?”

How different it was just across the border in Kansas: There, the late 1860s and early ‘70s were the era of Hickok and Custer, Cheyennes and Sheridan, railroad construction, cowtowns, and newly tilled grassland.

Missourians, by contrast, continued to fight the Civil War. Former guerrillas carried out more bank robberies in 1867, and Governor Fletcher continued his counterattack. He personally orchestrated arrests and ambushes. Angry mobs lynched jailed suspects. One by one, the senior members of Clement’s gang disappeared.

Missouri’s Republicans triumphed on all fronts. With victory, though, they splintered. In 1870, a break-away faction formed the Liberal Republican Party. It elected B. Gratz Brown as governor, with Democratic help. The Liberals also put a measure on the ballot to allow old Confederates to vote again. It passed easily. The voting ranks of the Republicans’ opponents effectively doubled.

A long-awaited opportunity opened for Confederates. But they had to overcome their numerical inferiority. They were a minority in the state, and made up only about half (if that) of the Democratic Party. To win control of the party—and thus the state—they would have to fight a cultural campaign. They would have to make Missouri Southern.

That was the strategy of a long-bearded, hot-blooded, and often drunk former Confederate named John Newman Edwards.

The Political Power of Memory

Listen to a recording of historian Karen L. Cox explaining the evolution of American views of the South in popular culture, at the Kansas City Public Library.

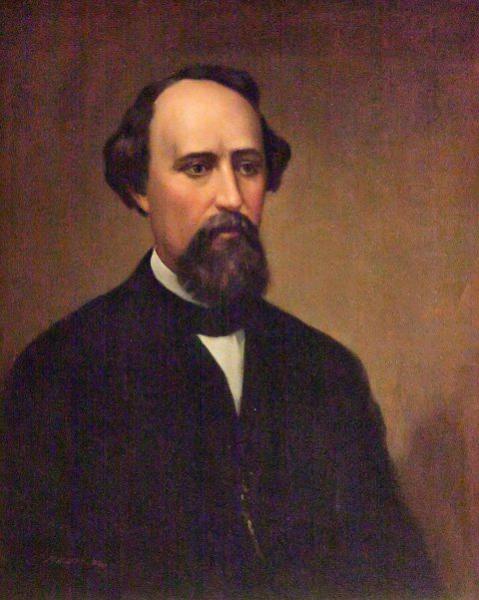

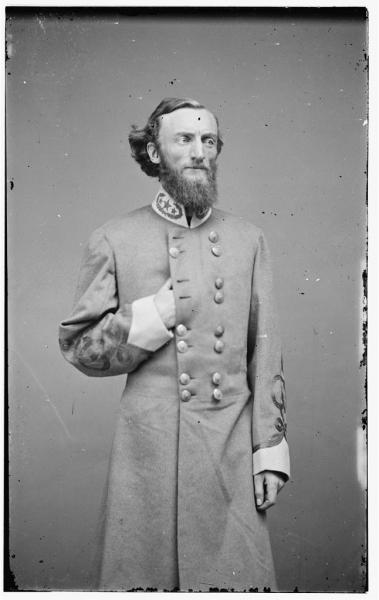

No one loved the South more than Edwards. In the 1850s, he worked for a Missouri newspaper that was wrecked by a raiding party of Free-Soil Kansans. He served as adjutant to Missouri’s most famous Confederate cavalryman, General Jo Shelby. Afterward they led their troops to Mexico rather than surrender.

In 1867 they returned. The next year Edwards helped found the Kansas City Times. As editor, he embarked on a project, quixotic at first, but increasingly central to the political fate of former Confederates. He set out to convince Missourians that they were Southerners - that they lived in the South.

He pursued several narratives in doing so. He depicted Missouri as the victim of an invading, oppressive federal government, aided by local traitors and collaborators. He put Missouri’s experience in a national context, arguing that it shared the fate of the South. And he glorified the state’s secessionist fighters, especially the guerrillas.

He began with a book, serialized in the Kansas City Times, titled Shelby and His Men. There and elsewhere, he praised the guerrillas’ extreme brutality. In Edwards’s writings, their savagery proved them “ultra-Confederate,” to use historian Matthew Hulbert’s term. Edwards cast them as the truest Missourians, the state’s heart and soul. “There are men in Jackson, Cass, and Clay [counties]—a few there are left—who learned to dare when there was no such word as quarter in the dictionary of the border,” Edwards wrote in 1872. The Radicals? They wrought nothing but “tyranny and oppression ... a destruction of the old order of things.”

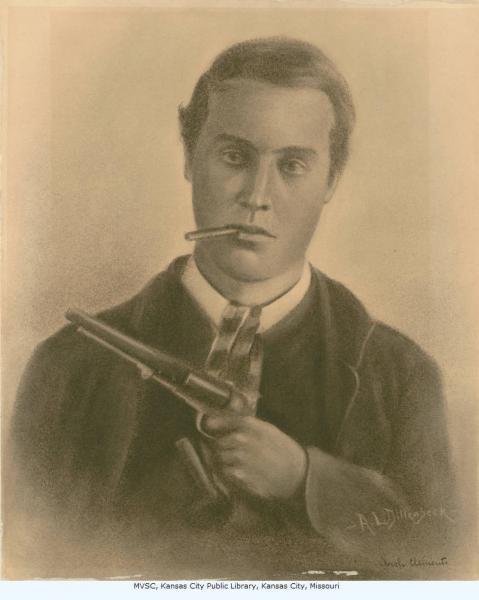

In 1869, Edwards found a face for his campaign. That December, a former guerrilla named Jesse James shot a bank cashier in Gallatin, Missouri, in a botched attempt at revenge on the man who killed Bloody Bill Anderson during the war. It made James notorious for the first time. It was the kind of notoriety Edwards liked.

Soon the two became friends. James, like Edwards, was highly partisan, and cooperated with the newspaper editor. In editorials and letters from James himself, Edwards cast the outlaw as the embodiment of western Missouri’s Southernness. He depicted James as a martyr to the Radical oppression - and as an avenger, a man who refused to hand in his guns and buckle to the new order.

Edwards was not the only Southern mythologizer. Peter Donan, founder and editor of the tellingly named Lexington Caucasian, followed an explicitly Confederate (and racist) editorial line. He wrote, “We are and have been Southern in our sympathies, and opposed to a mongrel breed, or a mongrel government.” (Mongrel meant mixed-race.) His paper railed against the Constitution’s “Yankonigger bayonet amendments” (a reference to the 13th, 14th, and 15th, Constitutional Amendments, which had granted freedom and civil rights to African Americans). Donan, too, praised Confederate guerrillas, and hailed the James-Younger outlaws as “pet institutions of Missouri.”

This campaign raised the pride of former secessionists. It also influenced Unionist Democrats on the border. They, too, had suffered disfranchisement and intimidation under Republican rule. The national struggle over Reconstruction gave them common cause as well. Conservative Unionists disliked emancipation, civil rights, and enfranchisement for African Americans, and the upending of border society.

Edwards eventually moved to St. Louis. There he edited the explicitly Confederate St. Louis Dispatch and continued his campaign. The constant propaganda gained force from such incidents as the Pinkerton detectives’ attack on the home of the family of Jesse and Frank James in 1875, in which their mother was maimed by an exploding incendiary device. Edwards and others depicted the raid as vindictive retribution for the James brothers’ Confederate allegiance by ruthless, invading Yankees.

In response, the Missouri State Assembly voted to grant amnesty to the bandits, in a remarkably pro-Confederate resolution apparently written by Edwards. During the war, it proclaimed, the James and Younger brothers had “gallantly periled their lives and their all in the defence [sic] of their principles.” The resolution ultimately failed, but the rebel tide in politics and culture was unmistakable.

“Is there, then, a scheme to make the [Democratic] party in this state, too, a Confederate party?” asked a Unionist newspaper. Yes, there was. Walter B. Stevens, city editor of the St. Louis Dispatch, recalled “the dominant way in which [ex-Confederates] were coming to the front.”

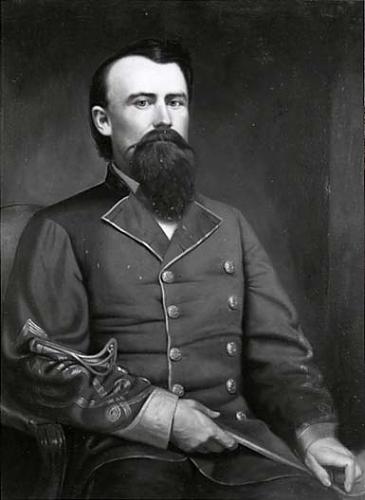

By 1879, both of the state’s U.S. senators were former secessionists, as were many of its U.S. representatives. In 1884, Confederate general John Sappington Marmaduke took office as governor. And when Edwards died in 1889, the Blue Springs Herald declared it a “great loss to the Democratic Party.” The Jefferson City Tribune wrote that the “prince of journalism was dead.”

History is rarely clear-cut. Unionists still shared power. Wartime divisions receded in time. Furthermore, many residents and parts of western Missouri never identified with the South. And those who did often had real family or personal connections to the Confederate cause. But old rebels clearly regained prominence, thanks in part to this cultural campaign. Their restoration reinforced that identity in turn.

The Final Twist

Perhaps Truman’s family story of stolen silver was true. Kansans did raid western Missouri, after all. But the tale reflects a final twist in the evolving memory of the border. Increasingly, Missourians recalled the Civil War as a struggle against outsiders. It was more comforting to put all the emphasis on rampaging jayhawkers and none on internal divisions. It was more uniting to depict a state that stood together against invasion. The myth became so deeply rooted that it would appear in scholarly histories well into the twentieth century.

Missourians recalled the Civil War as a struggle against outsiders. It was more comforting to put all the emphasis on rampaging jayhawkers and none on internal divisions.

The irony is that, economically and demographically, postwar Missouri followed in the wake of Kansas. Migration meant fewer Missourians were descended from Southerners, and fewer were black. The slave-based agriculture of hemp and tobacco faded behind corn and wheat, classic Kansas crops. Steamboats that once ran to New Orleans disappeared, replaced by railroads linked to Chicago. Kansas City had been a small town before the Civil War, but afterward it rapidly rose to become the economic capital of western Missouri. Rails and stockyards integrated it into the Kansas economy.

Yet economics is not destiny. Culture and memory still diverged, in part because of deliberate efforts by mythmakers such as Edwards. And so, decades after the Civil War ended, two presidents from contiguous states, serving consecutive terms, looked back and recalled two very different pasts.

Suggested Reading:

Astor, Aaron. Rebels on the Border: Civil War, Emancipation, and the Reconstruction of Kentucky and Missouri. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2012.

Blight, David W. Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press, 2001.

Fellman, Michael. Inside War: The Guerrilla Conflict in Missouri During the Civil War. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Geiger, Mark W. Financial Fraud and Guerrilla Violence in Missouri's Civil War, 1861–1865. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

Hulbert, Matthew. "Constructing Guerrilla Memory: John Newman Edwards and Missouri's Irregular Lost Cause," The Journal of the Civil War Era. March 2012.

Phillips, Christopher. The Making of a Southerner: William Barclay Napton's Private Civil War. Columbia, Mo.: University of Missouri Press, 2008.

Stiles, T.J. Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002.

Cite This Page:

Stiles, T.J.. "The Border of Memory: The Divided Legacy of the Civil War" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Thursday, April 25, 2024 - 15:54 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/essay/border-memory-divided-legac...

Rights/Licensing:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License