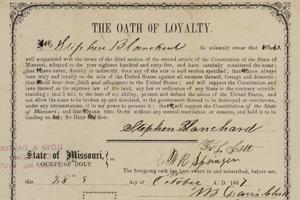

An Oath of Loyalty, which the radicals' new state constitution demanded of anyone who wanted to vote, run for office, serve on a jury, teach in public schools, or conduct other public business.

By Jason Roe, Kansas City Public Library

Each month in 2014, the Library will commemorate the sesquicentennial of the Civil War in Missouri and Kansas with a post derived from the thousands of primary sources that are digitized and incorporated into this website. The Library and its project partners collaborated to assemble this rich repository from the collections of 25 area archives, combining it with interpretive tools and original scholarship produced by nationally recognized historians.

Radicals Elected in Missouri

At the beginning of November 1864, the upcoming elections overshadowed other events in Missouri and Kansas, leading to the formal emancipation of Missouri's remaining slaves and the partial disenfranchisement of Missourians who were considered disloyal to the Union. The remnants of Major General Sterling Price's Confederate "Army of Missouri," which had been defeated and ultimately crushed in the Battles of Westport, Mine Creek, and Newtonia the month before, were fleeing through Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) on their way to regroup in Texas. Price's army would never present a threat to the Union again, but a few followers remained with him near Clarksville, Texas. Following the war, Price and a loyal subordinate general, Joseph "Jo" Shelby, and about 1,000 of their followers refused to accept defeat and crossed the Mexican border, founding the short-lived Confederate colony of Carlota, which was located midway between Mexico City and Veracruz and dissolved in 1867.

The spectacular devastation left in the wake of Price's "Missouri Expedition" cast a pall over Missouri's conservatives in the November 8 elections. Voters in Missouri and throughout the North were inclined to support candidates who took a hard line against the Confederacy. Aside from the destruction of his army, Price's most ambitious goals of establishing a Confederate military presence in the state and causing President Abraham Lincoln to lose his re-election bid foundered. Owing largely to the capture of Atlanta in September, Lincoln won the election handily and resolved to continue the war. In Missouri, so-called "radicals" defeated Democrats and moderate Republicans.

See digital copies of hundreds of loyalty oaths that are contained in the collection.According to historian T.J. Stiles, Missouri's radical Republicans, unlike the more famous "Radical Republicans" who gained a majority in the U.S. Congress, "were driven by a desire to punish secessionists, not by humanitarianism toward the slaves." The newly elected state representatives considered Southern sympathizers and Missouri slaveholders to be indisputable "traitors," who should be permanently disenfranchised from politics and stripped of their human property. Accordingly, voters also approved a ballot initiative that would formally end slavery in Missouri in January 1865. The election of Missouri radicals in November eventually resulted in the approval of a new state constitution, the so-called "Drake Constitution," in June 1865. Among the new provisions was the requirement that voters, candidates for office, jurists, teachers, preachers, lawyers, or businessmen take an "Iron-Clad Oath," a loyalty oath requiring individuals to declare that they had not engaged in any one of 86 offenses against the Union during the war. Price's Raid, which was in many ways the culmination of years of guerrilla warfare and a pattern of massacres and retributions along the Missouri-Kansas border, had now shifted political power to the Unionists who determined to permanently end secessionism in Missouri.

While modern historians can rightly claim that the worst of the unrest and danger had passed in Missouri and Kansas by November 1864, the fears that propelled those residents to elect radicals as their representatives were understandable. Only weeks had passed since one of the largest cavalry raids in U.S. history had scarred both states, and guerrilla warfare had reigned for several years in spite of the Union military ostensibly controlling both states. A letter to a resident of St. Louis summarized the prevailing mood, cautioning, "My advise would be for you to sell all your surplus stock &c get you and family to some safe place[,] our troubles are not over by a long ways." Indeed, the war continued well into the next year, and bitter animosities stemming from the conflict did not cease for decades to come.

Life Resumes after Price's Raid

Amid all of the unrest, regular citizens had to find ways to make a living and cope with the hardships associated with the war.

Some people attempted to track down their missing relatives in the wake of Price's Raid. A "Mr. Colgan" received a letter from Maurice E. Pitcher, a resident of Independence, Missouri, who wrote to give an update to Colgan about his son, Willie Colgan, a member of the Army of Missouri and incidentally a distant ancestor of Harry S. Truman's family. Pitcher wrote that Willie stayed with their family when Price's army captured Independence and stayed one night. Willie had asked Pitcher to send a letter to his father, telling him of his whereabouts, and once the lines of communication opened, Pitcher wrote reassuringly on November, 6, "he is looking quite well,--was well dressed--, and indeed he had no appearance of being ‘one of Price's starved to death, rag-muffins'." Pitcher still seemed uncertain about the fate of the raiding army, though, as he added,

They had a series of battle's from little blue (in this country) until within a few miles of Fort Scott, and you may well imagine they had a series of successes.... We hear no news now, from the army.--I think Price has left the State,--although he and his men seemed to be very sanguin that they would remain here during the coming winter.

For other area residents, economic and agricultural concerns ruled the day. Lisbon Applegate, a resident of Keytesville, Missouri, in the north-central part of the state, attempted to collect debts owed to him by William Heryford, Jr. Describing Heryford as a "mutual friend" of the other lender, Applegate expressed his "regret and disappointment" that Heryford did not deposit the $894.57 he owed at E.A. Damon & Co., in St. Louis, the previous summer. Applegate added "that your hogs are left in a bad fix. The negro boy Cyrus who was left by you to attend them was this week taken away by the Soldiers (his master having gone off with Price) and there is no one now to attend to them." Of course the same incident that presented a potential economic setback for Heryford also meant that a young slave gained his freedom after his master joined Price's army.

Due to the loss of the slave labor that Heryford had paid for to watch over his livestock, Applegate recommended that they sell the pigs and "apply the proceeds to payment of foregoing debts." Ending his letter in a curt manner, Applegate added in the postscript, "Your Uncle Bill R. was killed some two weeks ago. I have not time now to enumerate any particulars. LMA" Further correspondence showed that the hogs sold at a price of $825 later in the year, and Applegate and Heryford still appeared to be transacting business and considered each other friends.

For most Missouri and Kansas residents, the war produced direct economic hardships. Although nothing close to what the South was experiencing, inflation of the currency was a constant concern. In the month of Price's Raid, E.F. Slaughter, from Hickman's Mill, Missouri, near the modern "Grandview Triangle" in the Kansas City metropolitan area, wrote:

[The] crops are light here and grain is getting scarce and prices of every thing getting up, corn is one dollar per bushel, hay 15 dollars per ton[,] wheat 2.25 per bushel. But this is not half as high as goods in the stores[.] the farmer cant keep up with the merchant[.] It takes as much money now to get our domestic as our whole store bill used to be. I suppose you know all about high prices[.]

Shawnee Lands Taxed in Kansas

If white families who were relatively well off at the beginning of the war struggled, other populations whose sufferings predated the war were hit even harder. When the Kansas-Nebraska Act opened Kansas Territory for white settlement in 1854, the U.S. government began negotiating treaties to remove much of the Native American population of Kansas and move them to reservations in Indian Territory, present-day Oklahoma. Starting in November, 1856, lands held by the Delaware Indians were put up for sale to white settlers, followed by the lands of the Peoria, Kaskaskia, Wea, Piankashaw, and Shawnee in 1857. However, many Shawnees remained in Kansas and retained individual farmsteads in "severalty," or separate from the communal ownership of the tribe. At least for the purposes of taxation, the new state of Kansas argued that the Shawnee lands held in severalty were not a part of the Shawnee Tribe that, according to federal law, was supposed to be a sovereign nation, exempt from taxation.

The members of the tribe who remained in Kansas after it became a state and the beginning of the Civil War in 1861 did not fare well, as hinted at in a letter from November 21, 1864. In the letter, a man named Abelard Guthrie wrote to Senator James Henry Lane, one of the most prominent advocates for Kansas becoming a free state and a fervent abolitionist. Guthrie requested that Lane support his side in a case then under consideration in the Kansas Supreme Court. Guthrie (and later, the Kansas Supreme Court) held that only land owned communally by the Shawnee Tribe, and geographically clear of white settlers, would be considered a sovereign reservation that would be exempted from taxation. Because the Shawnees remaining in Kansas owned their land individually and geographically dispersed among white settlers, the state and the governments of Douglas, Johnson, and Wyandot Counties began taxing their property at a considerable sum of $15 per acre after Kansas became a state in 1861. Guthrie pleaded that ending the tax would deprive those counties of "sixty thousand dollars of taxes which they sorely need."

View a collection of maps of the Shawnee Indian Reservation in eastern Kansas, circa 1857.The Kansas Shawnees hired legal counsel, sued the state and counties, and most refused to pay their taxes in protest. Hedging their bets, a few of the wealthier Shawnee paid the taxes under protest as the case progressed through the courts. Meanwhile, war raged and many Native American tribes were split along Union and Confederate lines. In Indian Territory, the Choctaw and Seminoles sided with the Union. The Cherokee Nation divided its loyalties between North and South and fought its own tribal civil war. Southern Kansas and Missouri saw an influx of many refugee members of the so-called Five Civilized Tribes who had sided with the Union and were driven away from Indian Territory by tribal leaders. The Union organized them into the Indian Home Guard, which fought a number of engagements in Indian Territory and Arkansas. For their part, the Shawnee from Kansas became known as the "Loyal Shawnee," a name earned due to so many of their members fighting for the Union cause.

By the time the Kansas Supreme Court handed down its ruling against the Shawnee in February 1865, it was becoming clear that the members of the Shawnee Tribe had picked the winning side in the war. The U.S. Supreme Court eventually considered the Shawnee's case and, in 1867, overturned the ruling of the Kansas Supreme Court. The new ruling stated that when Kansas was admitted into the Union, it agreed to abide by the treaty stipulations that were reached by U.S. government, which, in the court's view, recognized individually-owned lands as sovereign, tribal lands, exempt from taxation and regulation by the United States, the state of Kansas, or its county governments. The ruling stated unequivocally: "It follows from what has been said that the Supreme Court of Kansas erred in not perpetuating the injunction and granting the relief prayed for." The same ruling also applied to members of the Wea and Miami Tribes in Kansas.

As described by John P. Bowes, author of Exiles and Pioneers: Eastern Indians in the Trans-Mississippi West, "this legal triumph arrived too late for most Kansas Shawnees. As soon as the Kansas Supreme Court announced its decision in February 1865, county officials began to sell deeds to Shawnee allotments for unpaid taxes and interest." Months before the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Shawnees, the Office of Indian Affairs had already declared that most of the Shawnee lands in Kansas had been sold off by the county governments. Most of the remaining Shawnees sold their land and relocated to Indian Territory, where in 1869, 722 of them joined the Cherokee Nation, becoming known as the Cherokee Shawnee. In 2000, the federal government recognized the Shawnee Tribe as a separate entity from the Cherokee, and it claims just over 2,000 members. Today, only a handful of Shawnees still own land that is legally a part of the Shawnee Reservation in Kansas.

Compared to the more infamous incident in U.S.-Indian relations of November 1864—the Sand Creek Massacre of November 29, in southeastern Colorado Territory—a letter written to Senator James H. Lane and the continuation of a Kansas Supreme Court case would barely warrant a footnote in most histories of the American West. But in many ways the tragedy of the American Indian Wars can be seen in the gradual and painful dislocations of native peoples, as well as in the legal subtly of the treaties their tribes were forced to sign, which only obfuscated the fact that they were losing most of their lands and property to white settlers.