By Kim Warren, University of Kansas

With the promise of freedom and new economic and educational opportunities, Kansas attracted many African Americans in its territorial days, through statehood, and into the 20th century. Slavery existed in the Kansas Territory, but slave holdings were small compared to the South. Many black migrants also came to the territory as hired laborers, while some traveled as escaped slaves through the Underground Railroad. In the 1860s, others joined the Union Army, and some moved from the South in large groups during the Kansas Exodus, a mass migration of freedpeople during the 1870s and 1880s. As a territory that had a long and violent history of pre-Civil War contests over slavery, Kansas emerged as the “quintessential free state” and seemed like a promised land for African Americans who searched for what they called a “New Canaan.”

Slavery in Antebellum Kansas and the Underground Railroad

Although there were relatively few slaves in territorial Kansas, enslaved men and women provided important labor along the Missouri-Kansas border. Unlike large plantations in the South, slavery in the border region existed in small holdings, permitted closer contact between slaves and slaveholders, and allowed slaves to hire themselves out with the permission of owners.

The issue of slavery’s expansion into the West turned Kansas into a battleground as it prepared to enter the Union. A bill passed in 1860 would abolish slavery in Kansas, but before then, antislavery settlers campaigned against proslavery factions. Abolitionists raised money for fugitives through aid societies and publicly argued against slavery on lecture circuits. Daniel Anthony, the brother of woman suffragist Susan B. Anthony, moved to Kansas in 1854 with the Massachusetts Emigrant Aid Society for the express purpose of fighting against the extension of slavery into the territory. Antislavery activities could be as violent and sporadic as John Brown’s vigilante raids on proslavery neighbors, or they could be more cautious and systematic, as were the secret Underground Railroad “stations” meant to shuttle escaped slaves to freedom.

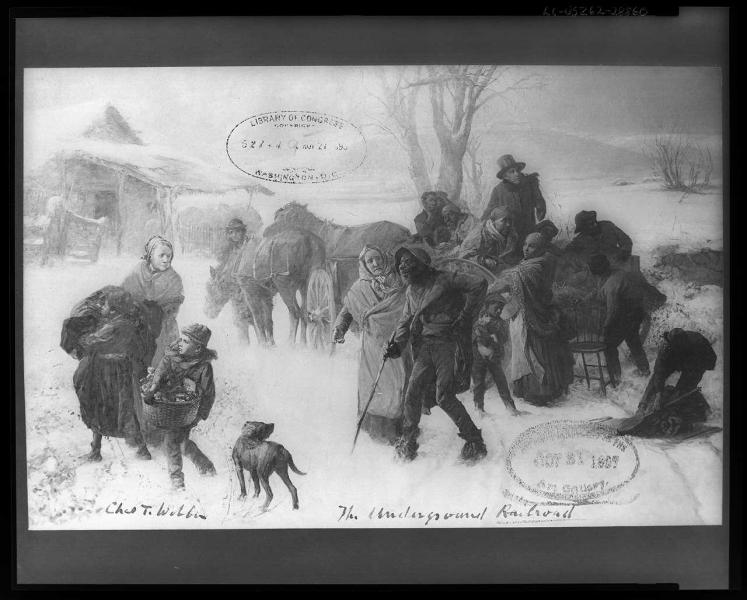

The Underground Railroad was not actually a train, but rather a large, national network intended to help fugitives escape from slavery into northern states and Canada. White and African American abolitionists created a large but informal network of hiding places in farmhouses and in the woods throughout the South, so that conductors could help passengers travel from station to station under the cover of night. Fugitive slaves and those who aided them risked their own safety, especially after the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act required the return of runaway slaves to their owners even if they had made it into a free state or territory. A 19th century minister once claimed that the number of escaped slaves who passed through his town of Lawrence, Kansas, amounted to $100,000 worth of property during the territorial period. Depots in Kansas proved to be especially important to fugitive slaves from Missouri en route to Nebraska, Iowa, and even Canada.

Quindaro residents established several Underground Railroad stations, where many African American slaves sought refuge on their way to freedom.

In some cases, abolitionists established new towns near the Missouri-Kansas border to reinforce the “cause of liberty.” An example of such a town is Quindaro, located in present-day Kansas City, Kansas. The name, Quindaro, was a Wyandotte word meaning “bundle of sticks,” which evoked an ideal of strength in unity. The town, founded in 1856, quickly grew because of its port near the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri rivers, as well as its subsequent establishment of surveyors, businesses, and stone and brick yards. The boom of Quindaro’s first year did not sustain the community for long, though, and by 1862 the state legislature had taken measures that led to the voiding of the town’s incorporation. However, during its existence, Quindaro residents established several Underground Railroad stations, where many African American slaves sought refuge on their way to freedom.

An example of a frequently used station was Quindaro’s high school for African Americans, established by a white minister, Eben Blatchley, in 1857. In 1865, Blatchley named the school Freedmen’s University, and in 1881 it was finally renamed Western University, with the sponsorship of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. The school lasted much longer than the town, gaining support from local communities and the state legislature and earning a reputation as a school where African American students could excel academically until its closure in 1943.

The Underground Railroad activities at Blatchley’s school maintained secrecy during the antebellum period, but in 1911, the school and the Quindaro community created a public reminder of its anti-slavery stance by installing a life-size statue of John Brown. For his leadership in a failed insurrection of slaves, Brown had been charged with treason and hanged for his attempt to start a slave insurrection at Harpers Ferry in 1859. The statue of the martyred hero stood in the front lawn of the school with a dedication: “Erected to the memory of John Brown by a grateful people.”

War and Increased Demands for Education

As skirmishes increased in Kansas in the years before the Civil War, so did a military buildup that included both whites and African Americans. Black soldiers joined Union troops as early as 1862 in the First Kansas Colored Infantry in the town of Fort Scott. Earning the distinction as the first African Americans engaged in Civil War battles, their initial combat took place at the Battle of Island Mound in Bates County, Missouri, in October 1862, even though the troops were not officially recognized by the federal army until a few months later.

For some, joining the military also increased their chances with literacy in an era when it was otherwise illegal in many states to teach slaves how to read.

Both escaped slaves and freedmen joined the Union Army because it ensured a certain amount of freedom for African American soldiers. For some, joining the military also increased their chances with literacy in an era when it was otherwise illegal in many states to teach slaves how to read. While in camp, soldiers would share each other’s letters and teach each other how to read the Bible. In 1865, when soldiers in the First Kansas Colored Infantry gathered their families to settle in Fort Scott, the Northwestern Freedmen's Aid Commission constructed a schoolhouse behind the officers' quarters of the military fort. At one point, the school served 160 children during the day and 75 adults in the evening.

Eventually the legislature would levy taxes on property owned by African Americans to be appropriated for such schools, but until then local communities and aid societies maintained black schools. Most schools for African Americans were separate from white schools, but since the territorial legislature had ordered that schools should be available without charge for all children between the ages of five and 21 years, a certain commitment to African American education remained. By the end of the 1880s, Fort Scott had opened an additional school for children of African American Union soldiers. By 1956, Fort Scott had opened a total of four schools for black students, including one that the inventor George Washington Carver briefly attended as a teenager.

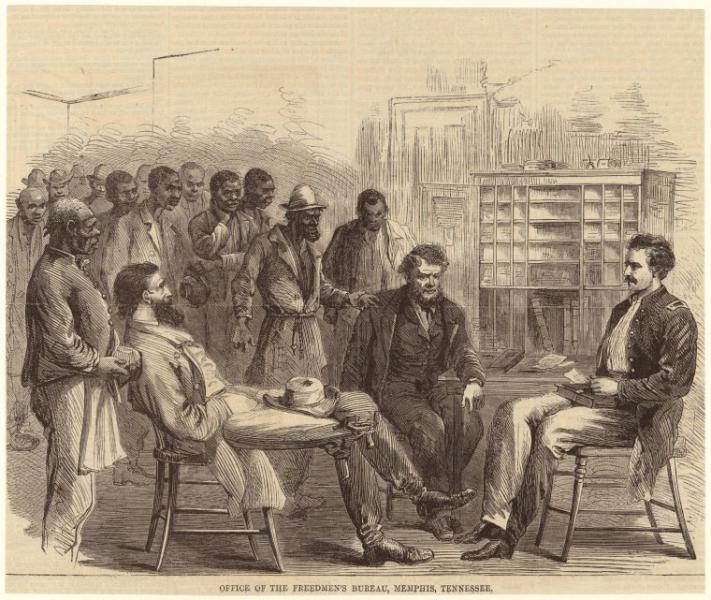

As more African Americans migrated to Kansas after the Civil War, the demand for education also increased. Federal assistance, however, did not. The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, a branch of the War Department in the federal government, had opened in March 1865 with the purpose of supervising relief activities for refugees and freedpeople. The efforts of the Freedmen’s Bureau included providing medicine, land, rations of clothing and food, and education, as well as providing overall support for African Americans’ transition from slavery to freedom. The existence of the Freedmen’s Bureau was threatened by President Andrew Johnson, whose second veto of its renewal and expansion in 1866 was overturned by Congress. Although the Freedmen’s Bureau continued until 1872, its funding was significantly cut by 1869 and its operations were mostly suspended. Therefore, without much federal assistance, African Americans were left to depend on each other, on white reformers, and on small organizations to fund their schools. As African American populations increased in towns such as Lawrence, Topeka, Leavenworth, and Tonganoxie, Kansas-based charity organizations also demanded that public school districts assume more responsibility for African American schools.

In general, white Kansans supported state and municipal legislation to fund African American education, although they did not necessarily call for the integration of public schools. Black students would continue to attend separate (although undoubtedly unequal) schools as long as the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson United States Supreme Court decision upheld the legality of segregation. In Leavenworth, for example, African Americans had their own school, but some described it as a “hut” situated in a “low, dirty-looking hollow close to a stinking old muddy creek, with a railroad running almost directly over the building.”

Despite such conditions and because of the voracious appetite for education among African Americans, civil rights organizations chipped away at Jim Crow laws that segregated white and black school children. Lawyers took 11 desegregation cases through courts of appeal up to the Kansas Supreme Court until Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas finally went to the United States Supreme Court in 1954. The Supreme Court unanimously decided against “separate but equal” policies of the past and called for the eventual integration of public spaces, including schools.

The Exodusters

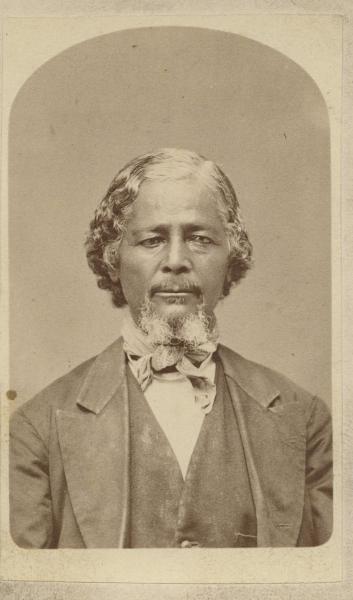

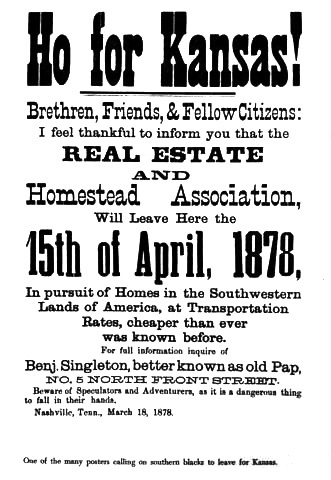

After the Civil War and the Reconstruction era, the cattle industry grew, and so did the number of African American cowboys throughout the West, but the largest catalyst for population increase was a desire among African Americans to escape the South and migrate to a free state. In the 1870s and 1880s with the failure of the federal government to provide adequate amounts of land, jobs, education, and protection for the millions of newly freed African Americans, thousands left their Southern homes. In 1879, Benjamin “Pap” Singleton, a former slave from Tennessee, became known as the leader of the “Exoduster Movement.” Kansas-based white reformers, such as Elizabeth Comstock, reported that African Americans suffered atrocities in Southern states: “Hanging, shooting, whipping, and mutilation have not ceased.” Lynchings of African Americans actually increased nationwide between the 1880s and 1930s, totaling over 3,000 during the period.

Kansas was not immune from Jim Crow segregation, race riots, or violence. Newspapers recorded incidents of a lynching of an African American man in Fort Scott and white mobs attacking African Americans held in local jails in Leavenworth, Topeka, and Kansas City. Gordon Parks, author, photographer, and director, spent his early years in Fort Scott, which he fictionalized as Cherokee Flats in the 1963 novel, The Learning Tree. His memory of Kansas included tranquil hills and the smell of delicious barbecue, but he also detailed memories of segregated restaurants, schools, and graveyards in his writing. For example, Parks described the protagonist’s hometown as especially complicated because of its position so close to the Missouri border, where the laws “stood for equal rights, but the law...never bothered to enforce such laws in such books.”

The idea that Kansas had a particular claim to freedom still appealed to African Americans, who saw migrating to Kansas as a positive alternative to their current conditions. “Leave the south if you have to crawl, come where you can have some protection,” the Afro-American Advocate claimed. Many African Americans thought of making new starts in the relatively young state of Kansas, where the possibility of “growing up with the country” reflected their optimism for more freedom. Some white politicians encouraged rhetoric that portrayed Kansas as especially welcoming to African Americans. For example, Jacob Winter, a state senator and civil right proponent, referenced Kansas as “this State that was born free; this State that stood in the front ranks in the great contest for freedom.”

Pap Singleton’s fliers urging African Americans to “Ho for Kansas!” ultimately prompted tens of thousands of individuals and families to leave the South. In an issue of the Wyandotte Gazette, the Freedmen’s State Central Organization called on several counties to prepare for the influx of refugees from southern states because “the dictates of humanity, as well as the honor and good name of Kansas demand that the destitute of this class of people should not be neglected, nor permitted to suffer for the necessary wants of life.”

Although Kansas had claimed to be the quintessential “free state,” Exodusters did not necessarily find the absolute freedom and equality that they had hoped to discover there. New residents brought with them large hopes for land ownership, but could not always successfully negotiate the purchase of property from white landowners. Many had to rely on aid societies, such as the Kansas Freedmen's Relief Association, for food and supplies. Local aid societies also intervened with Exodusters to provide them support for acquiring housing, job training, and education.

African Americans often established “black towns” or neighborhood colonies as distinctly separate from white communities. Segregation in black towns often meant fewer prospects of buying land and increasing job opportunities, but segregation also meant that black communities could concentrate their efforts on social uplift in their own communities. For example, in 1877, when 300 migrants from Scott County, Kentucky settled Nicodemus in Graham County, Kansas, they established their own churches and a school. They also prohibited saloons or other “houses of ill-fame” within the colony’s first five years. The trustees of Nicodemus recruited new residents by posting advertisements that referred to their establishment as a “beautiful Promised Land.”

In another black town, Tennesseetown, founded in 1880 within the city limits of Topeka, residents developed neighborhood improvement clubs, created a community library, and sent their children to a school that claimed to be the first African American kindergarten west of the Mississippi River. Elisha Scott, an African American lawyer who attended the Tennesseetown Kindergarten as a child, went on to establish a career as a civil rights lawyer and helped to argue the Brown v. Board of Topeka case before the United States Supreme Court. The court case, initiated in Topeka, Kansas, would not bring a conclusion to the state’s frequent contests over the meaning of freedom, but would stand as another important watershed moment in their long and ongoing struggle for civil rights that would continue for decades.

Suggested Reading:

Butchart, Ronald E. Schooling the Freed People: Teaching, Learning, and the Struggle for Black Freedom, 1861-1876. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Cox, Thomas. Blacks in Topeka, Kansas: 1865-1915, A Social History. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 1982.

Epps, Kristen K. "Bound Together: Masters and Slaves on the Kansas-Missouri Border, 1825-1865." Dissertation: University of Kansas, 2010.

Kluger, Richard. Simple Justice. New York: Random House, Inc., 1975.

Painter, Nell Irvin. Exodusters: Black Migration to Kansas After Reconstruction. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1976.

Warren, Kim Cary. The Quest for Citizenship: African American and Native American Education in Kansas, 1880-1935. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Williams, Heather Andrea. Self-Taught: African American Education in Slavery and Freedom. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Cite This Page:

Warren, Kim. "Seeking the Promised Land: African American Migrations to Kansas" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Thursday, April 25, 2024 - 21:02 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/essay/seeking-promised-land-afric...

Rights/Licensing:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License