By William E. Fischer, Jr., Fort Scott National Historic Site

The town of Fort Scott, established in 1855 on the former frontier fort grounds, quickly became embroiled in the debate over slavery. Populated primarily by those favoring the institution, many townspeople participated in “Bleeding Kansas” chicanery with outlying Free-Staters and abolitionists. When the Civil War erupted in 1861, the town was militarized and fortified to defend the state’s vulnerable southern approaches. But Fort Scott’s rich history even pre-dates these events.

“I respectfully recommend the abandonment of [Fort Wayne] and the establishment of a post. . . at some point about 100 miles south of Fort Leavenworth; perhaps near where the Military road crosses the Marmiton would be a good site.” So wrote Major Ethan Allen Hitchcock, 8th U.S. Infantry, to the Secretary of War on January 9, 1842. Fort Wayne had been established in Indian Territory in 1838 as part of the line of western fortifications along the Permanent Indian Frontier, but the subsequent high rate of malaria among its soldiers led to Major Hitchcock’s plea. By mid-May 1842, Captain Benjamin Moore, having scouted the area, declared the bluff overlooking the Marmaton River to be “the most eligible and important point between [Forts] Gibson & Leavenworth.” Within weeks, Fort Wayne was closed and Camp Scott, named for General Winfield Scott, was established by elements of the 1st U.S. Dragoons. The name was soon changed to Fort Scott.

...Fort Scott structures and remaining contents were sold at public auction in 1855. Yet because New York Indians retained title to the land given them during their forced westward removal, the buildings only brought pennies on the dollar.

While the infantry soldiers labored in constructing the fort and keeping the Military Road in good repair, dragoons patrolled the countryside. Their role was to keep the peace among Indian tribes and between the tribes and settlers who lived across the Missouri line, only a few miles east of Fort Scott. The post dragoons also participated in larger treks to protect wagon trains along the Santa Fe Trail. When the rumblings of war with Mexico sounded across the plains, most of Fort Scott’s garrison, which rarely totaled 200 men, was sent southwest. From June 1846 until September 1848, only Company B, 1st U.S. Infantry, maintained the post, typically with less than 50 men assigned. The unfinished fort remained unfinished at war’s end. Many former Fort Scott soldiers, including its first post commander, Benjamin Moore, lost their lives in Mexico.

With territorial annexation and westward expansion ending the concept of a Permanent Indian Frontier, Fort Scott was closed in 1853, the same year that Fort Riley was established further west. One non-commissioned officer and the former post sutler, Hiero Wilson, along with his family, remained on site as temporary caretakers. After the Kansas-Nebraska Act opened the territory to Euro-American settlement, the former Fort Scott structures and remaining contents were sold at public auction in 1855. Yet because New York Indians retained title to the land given them during their forced westward removal, the buildings only brought pennies on the dollar. It would take until 1860 for the town of Fort Scott to be incorporated and to gain clear title to the land.

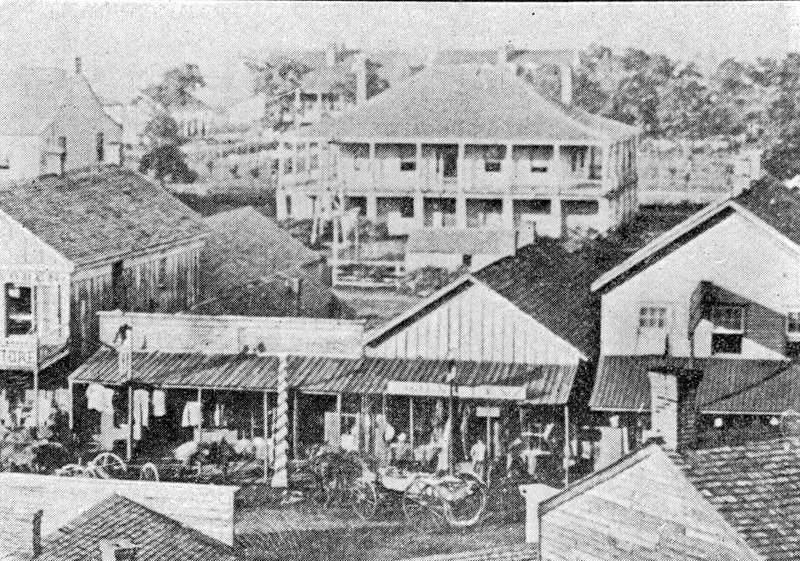

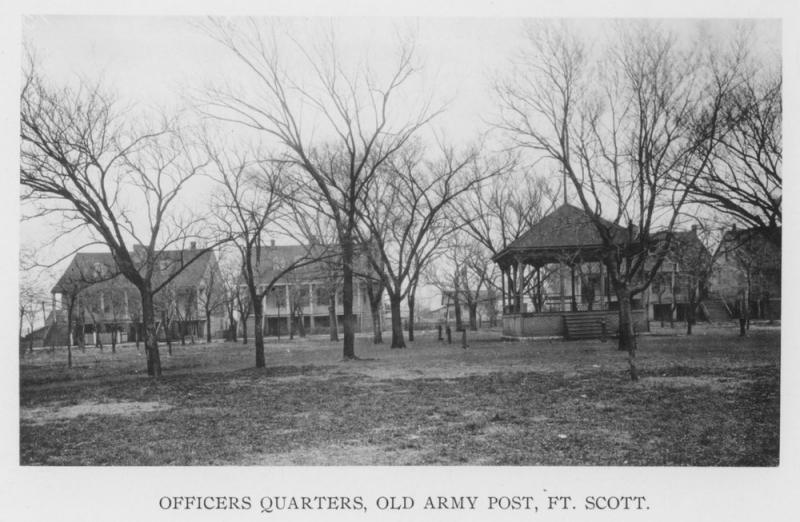

Despite the legal complications, the former frontier fort quickly became the nucleus of a growing civilian town. Being close to the slave state of Missouri, and with Hiero Wilson, the Kentucky-born, slaveholding former post sutler, and others of a similar political stance making the new town their permanent home, it’s not surprising that Fort Scott became a proslavery stronghold during the “Bleeding Kansas” era. Even the newly organized county, of which the town became its seat, reflected such sentiment, being named Bourbon in honor of the Kentucky county of the same name. As proslavery and abolitionist or Free-State factions flooded the territory, tensions escalated. Perhaps nowhere in Kansas was the dichotomy more visible than at the old fort where a former infantry barracks became the Western Hotel (also known as the Pro-Slavery Hotel), while directly across the parade ground, now a city park called Carroll Plaza, stood the Free-State Hotel in a former officer’s quarters.

Even the U.S. Land Office and Third Judicial District of Kansas, both established in Fort Scott in 1857, were tainted by the sectional intrigue. The proslavery rulings of Associate Judge Joseph J. Williams, who had been chief justice of the Iowa Supreme Court before his presidential appointment to the Kansas bench, and actions by land registrar George W. Clarke, were quickly declared foul by Free-Staters and abolitionists. Residing outside of town and in surrounding counties, they established their own “squatters’ courts” to address the injustices they perceived coming from Fort Scott.

Both sides began to organize for self-protection and increasingly sought vigilante justice. By the end of 1857, tensions had risen to a point that troops from Fort Leavenworth were called out to enforce peace. Soldiers returned to Fort Scott several more times during the territorial period, including with Governor James W. Denver in mid-June 1858. Earlier that month a failed abolitionist raid led by James Montgomery had descended on the town intent on burning down the Western Hotel, the rumored planning site for the Marais des Cygnes massacre. Denver’s so-called “Peace Convention” was highlighted nationwide in a Harpers Weekly illustration and provided a brief lull in the violence. By December, however, abolitionists returned to Fort Scott to free an imprisoned comrade. The resulting shootout led to the death of a former U.S. Deputy Marshal.

Still, with a growing Free-State population across the territory, in March 1859 the Bourbon County vote went 7-to-1 in favor of adopting the Wyandotte Constitution, which would bring Kansas into the Union as a Free-State. General calm ensued as many pro-slavers left Fort Scott. Anticipating growing prosperity in 1860, the area suffered through a serious drought, and after Lincoln’s election the town again hosted an Army contingent as uncertainty over secession in neighboring Missouri threatened that long awaited peace. Captain Nathaniel Lyon and his troops departed Fort Scott in the days following statehood (January 29, 1861) to defend the United States Arsenal in St. Louis.

Soon after the Civil War erupted, two companies of Home Guard were organized. Trained in martial skills by John Hamilton, a former Fort Scott dragoon sergeant living in town, some of these so-named Frontier Guard militiamen joined the 1st and 2nd Kansas regiments, which were then being mustered in answer to Lincoln’s call for volunteers. As Unionists and secessionists fought for control of Missouri, James Lane began assembling state forces in Fort Scott to defend Kansas’s vulnerable southern flank. The troops, loosely organized within Lane’s Brigade, would later be reorganized by the state. Additional Home Guard companies raised at Fort Scott were incorporated into the 6th Kansas Cavalry and later officially mustered.

...the general had designs on securing Missouri for the Confederacy and instead moved north, not knowing that Fort Scott had largely become a ghost town.

In the immediate aftermath of the Union defeat at Wilson’s Creek, some of the forces from Fort Scott, under the command of a now-commissioned James Montgomery, successfully skirmished with advancing rebel forces across the Missouri border at Drywood Creek in what became known as the Battle of the Mules. Although Fort Scott was evacuated in advance of a perceived onslaught by Sterling Price’s army, the general had designs on securing Missouri for the Confederacy and instead moved north, not knowing that Fort Scott had largely become a ghost town. But by late 1861, the settlement had become the militarized center of Union operations in southeast Kansas. It served as General James Blunt’s headquarters for much of 1862 and 1863. Regiments, which soon included out-of-state units such as the 3rd Wisconsin Cavalry that was based in the town for much of the war, received logistical support from Fort Scott’s growing military infrastructure, which included a supply depot and general hospital. The 1862 Union expedition to retake Indian Territory was launched from Fort Scott, and although it failed, the operation demonstrated the necessity of safeguarding the town for future offensive operations into Indian Territory, southwest Missouri, and northwestern Arkansas.

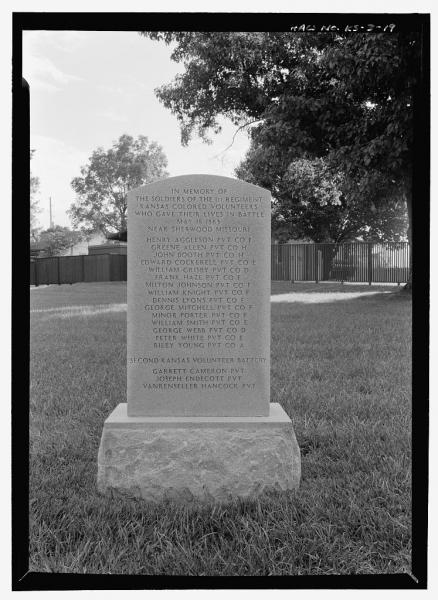

As casualties mounted, the local burial ground was designated as one of the original national cemeteries. And with the defensive buildup, Fort Scott became a safe haven for Union refugees and formerly enslaved people from across the region. With a growing populace of able-bodied African American men, James Lane disregarded instructions from superiors and formed the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry. The unit, which “fought like tigers” against bushwhackers at Island Mound, Missouri, in October 1862, was later mustered into federal service at Fort Scott, as was the 2nd Kansas Colored.

In late 1864, Fort Scott and eastern Kansas were once again threatened by General Price’s rebel army. Among the statewide call up of reservists, the 24th Kansas Militia was activated at Fort Scott with more than 1,000 men from Bourbon, Allen, and Woodson Counties reporting for duty. On retreat following decisive losses at Westport, Missouri, and Mine Creek, near Mound City, Kansas, Price’s men passed Fort Scott to the east, near where the battle at Drywood Creek had occurred three years earlier. Although the town once again avoided a devastating clash of titans, bushwhackers struck to the west of Fort Scott and killed six men, including the invalided Horatio Knowles, former Lt Colonel of the 2nd Kansas Colored Infantry, in what became known as the Marmaton Massacre. The uncivil cross-border guerrilla warfare that was spawned during territorial days had only escalated in intensity after 1860. Rooting out bushwhackers had become a standard mission for troops assigned to Fort Scott. As evidenced by the attack at Marmaton, it was no easy task.

Fort Scott continued to serve as a conduit for men and materiel as Union forces pressed the offensive and achieved victory in 1865. As irony would have it, the town of Fort Scott prospered from the military buildup and by the fact that it was never attacked during the Civil War. Peace, ten years elusive, now provided a chance for continued progress, and railroad expansion to and through Fort Scott became a primary means for such growth. The first rail line reached Fort Scott in December 1869, but its continued advance through southeast Kansas set the stage for a most unusual and unfortunate situation.

Squatters, many who had lost everything during the war and who were seeking a fresh start, came into dispute with railroad expansion through the Cherokee Neutral Lands south of Fort Scott. Shots were fired. To protect workers laying track, the U.S. Army established the Post of Southeast Kansas in 1870, with headquarters in the town of Fort Scott. Troops remained in the field until 1873, thereby ensuring the rails were laid and Fort Scott’s economic future was secured.

With such a rich and varied history, it’s not surprising that as the old pioneers began to pass from the scene, Fort Scott’s residents sought to remember the past. As a new century was dawning, local businessman Charles Goodlander and attorney Ralph Richards retold in print the stories of yesteryear, the Molly Foster Berry Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution placed historic plaques around town, and the Bourbon County Historical Society and the Business and Professional Women’s Club operated historical museums. Tireless work in the late 1950s by Judge Harry Fisher, Professor Dudley Cornish, Congressman Joe Skubitz, and many others led to the extant remnants of Fort Scott being listed as a National Historic Landmark in 1964. Fort Scott Historical Park, centered on the former frontier fort’s parade ground, was developed soon after as a city-operated site. Then, in 1978 the city signed over the property for inclusion as a unit of the National Park System known as Fort Scott National Historic Site, where the stories of old continue to be told.

Suggested Reading:

Greenwald, Emily, and Joshua Pollarine. Reclaimed from Obscurity, Preserved for Posterity: An Administrative History of Fort Scott National Historic Site, Fort Scott, Kansas. Omaha: National Park Service Midwest Regional Office, 2013.

Holder, Daniel J., and Hal K. Rothman. The Post on the Marmaton: A Historic Resource Study of Fort Scott National Historic Site. Omaha: National Park Service Midwest Regional Office, 2001.

Oliva, Leo E. Fort Scott: Courage and Conflict on the Border. Topeka: Kansas State Historical Society, 1984, rev. ed. 1996.

Richards, Ralph. The Forts of Fort Scott and The Fateful Borderland. Kansas City, Missouri: The Lowell Press, 1976.

Cite This Page:

Fischer, William E., Jr.. "Fort Scott, Kansas" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Thursday, April 18, 2024 - 19:06 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/fort-scott-kansas