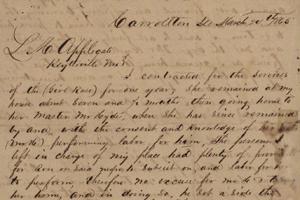

From William Heryford Jr. to Lisbon Applegate. Image courtesy of the State Historical Society of Missouri – Columbia.

By Jason Roe, Kansas City Public Library

In the spring of 2015, the Library commemorates the sesquicentennial of the final months of the Civil War in Missouri and Kansas with a post derived from the thousands of primary sources that are digitized and incorporated into this website. The Library and its project partners collaborated to assemble this rich repository from the collections of 25 area archives, combining it with interpretive tools and original scholarship produced by nationally recognized historians. Sign up to receive this newsletter via email »

Ending Slavery in Missouri

Just one month before Robert E. Lee's surrender at Appomattox, the Confederacy's economy and ability to wage war were nearly crippled. Following President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, many slaves from seceded states were either freed by advancing Union forces or took advantage of the chaos to escape to freedom. While Lincoln's proclamation did not legally end slavery in border states that remained loyal to the Union, including Missouri, the progression of the war placed slavery in an increasingly precarious situation as slaves joined Union forces, escaped to neighboring free states, or were manumitted by their masters who wanted to prove Northern loyalties or who simply recognized that slavery had ended. Finally, on January 11, 1865, Missouri officially abolished slavery, but in March 1865 it was already clear that slavery could not be erased without ongoing legal ramifications and social strife.

Several members of the Applegate family who resided in Chariton County in the north-central part of Missouri personified slaveholders' bitter resistance to the end of slavery. The county was located in the heart of Missouri's "Little Dixie" region (roughly aligning with the Missouri River valley, which provided a favorable environment for small-scale slave plantations) and, at the outset of the war, had more than double the percentage of enslaved persons of the state as a whole. It is clear that, at least to an extent, the Applegate family had invested in the institution of slavery and relied on the notion that African American slaves were nothing more than property.

The patriarch of the family, Lisbon Applegate, received a letter written on March 24, 1865, from a man named William Heryford, who had secured Applegate as his power of attorney to oversee his property in his absence. Heryford complained that although he had contracted with a Mr. Hyde for the services of an enslaved girl, referred to as "Girl Rose," for one year, Mr. Hyde took the girl back to his own home after only seven and a half months. Heryford requested that Applegate investigate whether this was true and, if so, hire an attorney to secure compensation from Mr. Hyde. Heryford summarized, "I am willing to pay for the time the negro remained at my house and no longer." Heryford wrote his letter two months after Missouri abolished slavery, showing that previous legal disputes would not end with abolition.

Lisbon Applegate's son, George Applegate, revealed his own views on race when he wrote from Lisbon, California, to his brother, James Applegate, on March 3, 1865. The town of Lisbon, which was more widely known as "Bear River House" or later, "Applegate," had been established as a fruit-growing "ranch" by Lisbon Applegate in 1849, although Lisbon moved back to Missouri by the time of the Civil War. George wrote to say that he was heavily indebted but still using his loans to expand his vineyards. More revealing, though, are George's statements about politics in the letter. He objected to Missouri's abolishment of slavery and wrote:

I see Mo. Goes straight on in her radical course and seems to be more abolitionist than the delectable state of Massachusetts, what do the people mean. a negro attorney was admitted to practice in the supreme court of the U.S. Nothing serves to satisfy the [Republicans] so well as to raise themselves upon a level with gentlemen of color and sniff the fragrance of the darkie in preference to all roses. All the harm I wish them is that they may indure all the evil their suicidal course is bringing on our once happy land, but such cannot be the case as all must suffer to expiate the crimes of the few.

Southern Sympathizers Look to Mexico

While easily overlooked, George Applegate's additional comments on an "occupation of Mexico" captured the Confederate distaste for their probable defeat in the war. He referenced the government of the Second Mexican Empire, which was essentially a puppet government of Emperor Napoleon III's France, headed by Emperor Maximilian I. Applegate described "thousands of southern men," who "were going down on the steamer to become subjects of his [Maximilian's]." This account aligned with the last months of the Civil War, as Confederate soldiers reconciled themselves to the prospects of defeat.

While the vast majority of Confederates surrendered or simply laid down their arms and returned home, some feared Northern occupation and retaliations or resented the notion of living in a society with a free black population, and some thousands decided to leave the United States altogether. Additionally, the French intervention in Mexico, with its imperialist intentions of encroaching on American commercial interest in the Western Hemisphere, had been problematic for the Lincoln administration since it began in late-1861. The Confederate government had attempted to provoke conflict between the Maximilian government and the Union, which could have brought France into the war in support of the Confederate rebellion. In this context, supporting the Maximilian government would be an honorable way of continuing the fight against the Union, at least in an abstract way and under a different banner.

George Applegate regretted that a number of Southerners had been blocked from immigrating to Mexico. He continued the theme of viewing Union authorities as oppressors, writing that General Irvin McDowell "put an embargo on the shipping and no more can have ... permission from the august master of our destinies."

Shelby's Undefeated "Iron Brigade"

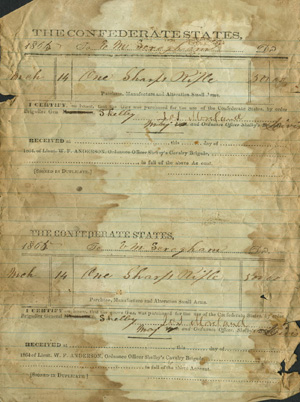

Thousands of Confederates sought an honorable exit from the prospect of living under a Northern occupation. The establishment of the Freedman's Bureau on March 3, 1865, which would oversee the Reconstruction policy following the war, underscored that the war was coming to an end and that the federal government would be considering how to enforce the abolishment of slavery and reintegrate the seceded Southern states into the Union. While the North planned for the postwar period, tens of thousands of Confederates continued fighting. At this late date, for example, this order for a Sharps rifle was issued under the name of Brigadier General Joseph O. Shelby.

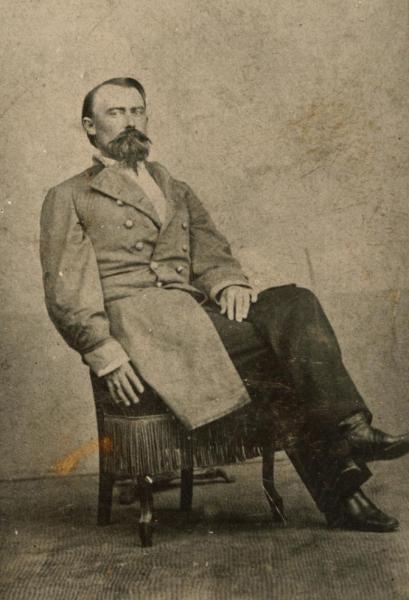

Known as "Jo" Shelby by his men, he was soon to become one of the notorious ex-Confederates who refused to surrender at the end of the war. For the first two years, he had served as a colonel or brigadier general in many of the major battles in Missouri and Arkansas. He emerged as a celebrated cavalry commander, leading a "Great Raid" from southwestern to north-central Missouri from September to November 1863. Finally, he led one of the three divisions of Major General Sterling Price's Army of Missouri in "Price's Raid" in September and October of 1864. After Price's defeats at Westport, Mine Creek, and Newtonia, Shelby led the tattered remnants of his "Iron Brigade" to Texas, where they remained until the end of June 1865 when they finally departed for Mexico.

At a stunning amount of $500, the price of the Sharps rifle that Shelby ordered in March 1865 exhibited the rampant inflation in the Confederate economy and the futility of Shelby's efforts. Comparatively, a muzzle-loading Springfield rifle, the most commonly used in the Civil War, typically cost $20 for the Union, and while the price of the relatively rapid-firing, breach-loading Sharps rifle or carbine was commonly three times as much as a Springfield, the rest of the price difference can be attributed to the collapsing Southern economy. With the war effort and a Union blockade in place, Southern cotton production and trade plummeted, wiping out the economic foundation of the Confederacy. While the Union was able to fund the vast majority of its war effort through bonds and taxes, and relied to a lesser extent on printing paper money, individual Southern states could print their own money and were reluctant to levy taxes for a rebellion against the federal government of the United States. By the end of the war, prices in the Confederacy had risen by a total of 9,000 percent, making, for example, the typical pair of shoes that cost a dollar at the beginning of the war more than $90 at the end. By contrast, inflation only totaled about 70 percent in the Union by the war's end. About half of the inflation in the Confederacy emerged in the last year of the war, as their currency system all but collapsed.

The Sharps order does not specify where this rifle originated, but with most arms manufacturing based in the North at the outset of the war, the Confederacy was forced to procure weapons by smuggling them from European manufacturers (especially in the case of the British Enfield rifle), recovering Union weapons lost on battlefields, relying on soldiers to bring their own shotguns and rifles (presenting an issue with non-standardized ammunition in Confederate armies), or making copies of Northern weapons despite shortages of materials, manufacturing capacity, and engineering expertise. While generally considered inferior in durability and other characteristics, the Confederacy produced workable copies of Sharps rifles at Richmond, Virginia.

The Undefeated, a 1969 film starring John Wayne and Rock Hudson, was loosely based on Joseph O. Shelby's march to Mexico.By March 1865, Shelby and his men had resided in Texas for several months, but in April, the surrender of Robert E. Lee and Joseph E. Johnston made it clear that the Confederacy would not survive the war. In addition to the arms that Shelby continued to purchase, his men raided abandoned Confederate arms and ammunition caches, accumulating thousands of weapons that could later be sold in Mexico. On July 1, 1865, Shelby crossed the Rio Grande and led an undetermined number of men from his "Iron Brigade" to Mexico, where they courted both sides: the French imperialist Maximilian regime and the republican resistance, led by Benito Juarez. As described in General Jo Shelby's March, by Anthony Arthur, Shelby believed that siding with the anti-imperialist and republican Juarez would best align with Confederate values, but Shelby's men detested the notion of siding with the non-white Juarez, who had received encouragement from Abraham Lincoln himself. They reasoned that it was better to side with the French regime and Maximilian I, who was originally a white archduke from the Royal House of Austria. Shelby arranged the sale of most of the weapons they had collected to Juarez in exchange for safe passage, but ended up siding with Maximilian I.

For his part, Maximilian ultimately resisted Shelby's overtures of siding with him against Juarez. Maximilian and the French government viewed the support of ex-Confederates as unreliable, and after Shelby's men fought in a few small engagements against Juarez supporters, Maximilian invited Shelby and other ex-Confederates to abandon the fight and establish colonies in Mexico. Shelby settled in the Carlota colony in Cordoba, about 180 miles southeast of Mexico City, where he established himself in the freight business. Following Maximilian's defeat and execution by Juarez forces in 1867, Shelby returned to Missouri, where he farmed and served a stint as the U.S. marshal for the Western District of Missouri from 1893 until his death in 1897.

As of March 1865, though, all records indicate that Shelby was prepared to resume fighting despite the deluge of discouraging news from the East. Nonetheless, Shelby and other likeminded Confederates would have little opportunity to continue fighting with the impending breakup of the Confederate States America in April and May.