By Chris Rein, Combat Studies Institute, Army University

Event Summary:

- Date: May 24-25, 1856

- Location: Pottawatomie Creek, Franklin County, Kansas

- Adversaries: Abolitionists affiliated with John Brown vs. proslavery Kansas settlers

- Casualites: Five proslavery fatalities

- Results: Massacre of the proslavery settlers

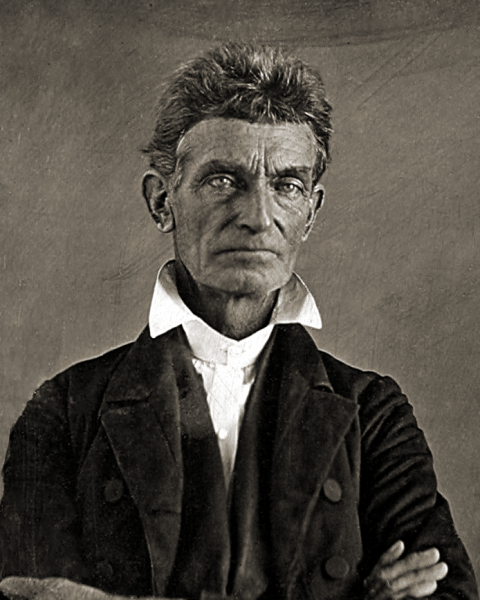

On the night of May 24, 1856, the radical abolitionist John Brown, five of his sons, and three other associates murdered five proslavery men at three different cabins along the banks of Pottawatomie Creek, near present-day Lane, Kansas. Brown had been enraged by both the sacking of the anti-slavery town of Lawrence several days before and the vicious attack on Charles Sumner on the floor of the U.S. Senate, in which Representative Preston Brooks, of South Carolina, relentlessly beat Sumner with a cane. The killings at Pottawatomie Creek marked the beginning of the bloodletting of the “Bleeding Kansas” period, as both sides of the slavery issue embarked on a campaign of terror, intimidation, and armed conflict that lasted throughout the summer.

Three days prior to the massacre, on May 21, Brown and the “Pottawatomie Company,” an informal militia group, marched toward Lawrence to protect the town from the proslavery men intent on its destruction. After joining with a similar company from the anti-slavery town of Osawatomie, the men traveled north until they received word that they were too late to prevent the attack on the town, which resulted in the destruction of the Free State Hotel and the offices of the free state newspapers, as well as the looting of many homes and businesses.

While camped near Palmyra, Brown resolved to take his revenge on his proslavery neighbors.

While camped near Palmyra, Brown resolved to take his revenge on his proslavery neighbors and enlisted the help of an associate, named James Townsley, to carry him, his sons Frederick, Oliver, Owen, Salmon, and Watson, as well as his son-in-law Henry Thompson back toward Pottawatomie Creek while a sympathetic Theodore Weiner followed on horseback. After crossing Mosquito Creek, the men camped for the night of May 23rd and most of the following day.

Around 10:00 p.m. on the 24th, the Brown party left their campsite, headed for the cabin of proslavery settler James Doyle, and demanded that he and his sons come outside. They were led a short distance from the cabin, where John Brown shot James Doyle in the head with his pistol as two of Brown’s sons hacked James's sons, Drury and William Doyle, to death with swords. A third son, 16-year-old John Doyle, was spared.

The party then traveled to Allen Wilkinson’s home, where, against the protestations of Wilkinson’s wife, who was sick with the measles, they took Wilkinson and hacked him to death, leaving his body alongside the road.

They then crossed to the south bank of the creek at Dutch Henry’s ford (named for “Dutch” Henry Sherman) and approached the home of James Harris. Here Brown’s group found several men and questioned them about their views on slavery and whether they had participated in the attack on Lawrence earlier in the week. William Sherman’s answers did not satisfy Brown, and he was killed behind the residence and his body left in the creek. The Browns then disappeared into the night.Shortly after the massacre, Eastern abolitionists seeking to distance Brown from it denied his presence there. However, an 1879 testimony by James Townsley, an abolitionist friend of Brown, indicates that Brown personally led the massacre.

They did not, however, disappear from the "Bleeding Kansas" scene. News of the attacks inflamed the territory, as both pro- and antislavery families fled for their lives. The irregular warfare extended beyond political motivations – it became personal and mercilessly brutal. Men on both sides continued to organize into armed groups and began patrolling the area in search of their enemies, resulting in engagements such as the Battle of Black Jack (where Brown took a number of proslavery men prisoner) and the Battle of Osawatomie, in which Brown and his men were unable to protect the anti-slavery town from being looted and burned by border ruffians and Brown’s son Frederick was killed.

By fall, the new territorial governor, John Geary, had largely restored order in the territory, although violence flared up regularly until 1858 and periodically after that. The Pottawatomie Massacre and the other attacks that marked “Bleeding Kansas” are considered by many historians to have been the opening shots of the Civil War.

Suggested Reading:

Etcheson, Nicole. Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004.

Goodrich, Thomas. War to the Knife: Bleeding Kansas, 1854-1861. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1998.

Reynolds, David S. John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005.

Cite This Page:

Rein, Christopher. "Pottawatomie Massacre" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Wednesday, April 24, 2024 - 00:07 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/pottawatomie-massacre