On May 1, 1865, President Andrew Johnson orders a military tribunal to try eight suspects in the Lincoln assassination case. The suspects are Samuel Arnold (who was complicit in a previous failed attempt to kidnap Lincoln), George Atzerodt (who was tasked with assassinating then-Vice-President Johnson but lost his nerve), Lewis Powell (who attempted but failed to assassinate Secretary of State William H. Seward on the night of Lincoln's assassination), David Herold (who aided Powell in his assassination attempt and John Wilkes Booth in his escape), Dr. Samuel Mudd (a physician who is accused of conspiring in the assassination plot and treating Booth's leg that was broken at Ford's Theater), Michael O'Laughlen Jr. (who conspired in the attempted kidnapping of Lincoln, but possibly not in the assassination itself), Edmund Spangler (an employee at Ford's Theater with questionable connections to the assassination plot), and Mary Surratt (the owner of the boarding house where Booth and the other conspirators plotted the assassination). The assassin, Booth, refused to be taken alive on April 26.

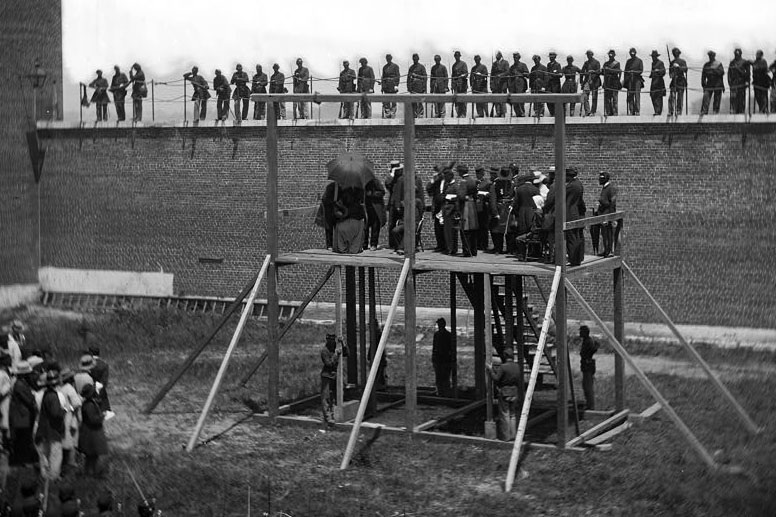

The tribunal finds all of the suspects guilty of their respective crimes, and four of them (Surratt, Powell, Herold, and Atzerodt) are sentenced to death by hanging. Most controversial is the sentencing of Mary Surratt, as the evidence against her is mostly circumstantial and related to the fact that she is acquainted with the conspirators, and that her son John H. Surratt Jr. (also a suspect), eluded capture. The tribunal votes six-to-four for her execution (only two-thirds majority is required, unlike in a civilian court), Surratt is denied appeal or clemency, and on July 7, 1865, she becomes the first woman to be executed by the U.S. government. On that day, these four conspirators are hanged.

The other four convicted conspirators serve varying terms in prison, with the extent of Dr. Mudd's complicity remaining an enduring controversy. In 1869, President Johnson finally pardons Mudd, who maintains his innocence until his death in 1883.