By Tony O’ Bryan, University of Missouri-Kansas City

Constitution summary:

- Date originally drafted: October 1855

- Stance on slavery: prohibited

- Suffrage for women: none

- Suffrage for African Americans: none

- Suffrage for Native Americans: "every civilized male Indian who has adopted the habits of the white man"

- Settlement by free African Americans: prohibited by an "exclusion clause" that was approved by Kansas voters (the version of the Topeka Constitution that came under consideration in the U.S. Senate lacked this clause, even though Kansas voters had elected to include it)

- Status: failed to achieve federal recognition by January 1857

Free-Soil settlers in Kansas created the Topeka Constitution and elected their own legislature to manifest the democratic ideals of popular sovereignty (letting settlers and their legislatures, rather than the federal government, decide on the status of slavery in future states) and bring their struggle against proslavery forces in Kansas Territory to a national audience. The fractious and extralegal 1855 constitutional convention joined together factions of Whigs, Democrats, Republicans, and Free-Soil advocates to fight against the increasingly virulent proslavery movement in the Kansas Territory. When the ballot box failed to solve the dispute, settlers turned to bullets to settle their differences, and the violence over slavery in the territory brought “Bleeding Kansas” to national attention.

The Topeka Constitution called for Kansas territorial citizens to alter their form of government, overthrow an oppressive regime, and repel foreign invaders.Echoing the rhetoric of Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence, the Topeka Constitution called for Kansas territorial citizens to alter their form of government, overthrow an oppressive regime, and repel foreign invaders – in this case the proslavery settlers and Missouri border ruffians who had fraudulently participated in the March 30, 1855, territorial election and established a proslavery territorial legislature. Once ensconced in office, that legislature, led by proslavery lawyer and politician Benjamin F. Stringfellow, tried to drive Free-Soil settlers out of the territory by enacting slave codes that were repressive and hostile not only toward abolitionists, but also to anyone even mildly unsupportive of slavery. Slave code laws were passed that forbade men known to hold antislavery opinions from serving on juries. Further, it was a felony to deny someone the right to hold slaves, and circulating published materials that encouraged slave insurrection was punishable by death.

During the summer of 1855, in Lawrence, Kansas, Free-Soil advocates such as James H. Lane and abolitionist Charles Robinson expressed daring opinions against the proslavery legislature and its oppressive slave codes. Although the Free-State men varied in their opinions of slavery, some believing in liberty for all, others in liberty only for white men, they coalesced a political party around the desire to make Kansas a free state. They looked to the precedent of California’s statehood, which emerged after a popular convention drafted a constitution and the territory was accepted into the Union as part of the Compromise of 1850. The Free-State Party moved in a similar direction on September 5, 1855, when it met at a convention in Big Springs, Kansas, declared the federally recognized proslavery legislature “bogus,” elected its own legislature and delegate to Congress, and called for a state constitutional convention in Topeka to begin in October.

Although the Free-State men varied in their opinions of slavery, some believing in liberty for all, others in liberty only for white men, they coalesced a political party around the desire to make Kansas a free state.With Jim Lane serving as president, the Free-State convention met from October 23 to November 11, 1855, in Topeka, Kansas. The drafted constitution prohibited slavery, granted citizens the rights to “life, liberty, and property and the free pursuits of happiness,” and extended suffrage to white men and “every civilized male Indian who has adopted the ways of the white man.” For reasons founded on racist attitudes and a desire to avoid economic competition, some Free-Staters believed Kansas should be open to settlement for whites only, and Lane forced the issue by including an "exclusion clause" banning free blacks from entering Kansas Territory.

The Topeka Constitution and Lane’s attached ballot were put to a territory-wide popular vote on January 15, 1856. In a landslide election, boycotted in protest by proslavery settlers but this time ignored by the border ruffians, the voters adopted the Topeka Constitution and chose Charles L. Robinson for governor. Voters also approved the ban on free black settlers. Kansas Territory now had two competing legislative bodies, one proslavery and the other Free-State.

The Topeka Constitution was forwarded to Washington, D.C. for approval, where President Franklin Pierce delivered a message to Congress that condemned the actions of the Free-State Kansans as, “of a revolutionary character,” and committed military force in support of the proslavery Kansans. The House of Representatives, however, accepted the Topeka Constitution and voted to accept Kansas’s statehood. Meanwhile, the Senate blocked the process by suggesting that Free-State Kansans reframe their constitution and sent the measure back to the House, which refused to consent.

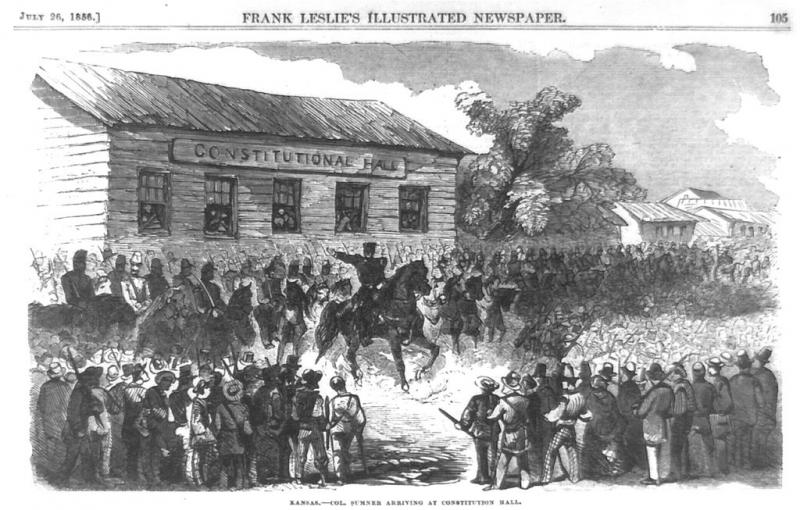

When the elected Free-State legislature attempted to convene at Topeka on July 4, 1856, Colonel Edwin V. Sumner, under authority of President Pierce, dispersed the meeting with a threat of force from two companies of the U.S. First Cavalry and a cannon. Embittered Free-State Kansans, radicalized at each step of this process toward statehood, finally took their fight directly to the proslavery side in a series of attacks on the proslavery settlements of Franklin, Fort Saunders, and Hickory Point, contributing to the territory’s reputation as “Bleeding Kansas.”

In January 1857, the Kansas Free-State legislature met again and resubmitted the constitution to Washington, where President James Buchanan, who supported the competing proslavery Lecompton Constitution, condemned the petition and stalled its adoption after his inauguration in March. Although the Topeka Constitution failed to gain statehood for Kansas, it drew the attention of the nation to the Free-State cause, stimulated heated national debate over the issue of slavery, and became a central campaign issue of the 1856 presidential election. The struggle over the Topeka Constitution fostered the fledgling Republican Party and inspired waves of Free-State immigrants to Kansas—along with the associated guns and money—which would finally settle the issue of popular sovereignty in Kansas.

Suggested Reading:

Etcheson, Nicole. Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004.

Goodrich, Thomas. War to the Knife: Bleeding Kansas, 1854-1861. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1998.

Cite This Page:

O’Bryan, Tony. "Topeka Constitution" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Friday, April 19, 2024 - 14:20 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/topeka-constitution