By Matthew E. Stanley, Albany State University

Biographical Information:

- Date of birth: February 24, 1802

- Place of birth: Barnesville, Ohio

- Claim to fame: member of the U.S. House of Representatives, March 4, 1853-March 3, 1855; governor of Ohio, December 13, 1838-December 16, 1840, and governor of Ohio again December 14, 1842-April 15, 1844; 2nd territorial governor of Kansas

- Political affiliations: Democratic Party

- Date of death: August 30, 1877

- Place of death: Lawrence, Kansas

- Final resting place: Oak Hill Cemetery, Lawrence

Wilson Shannon was an attorney, the 14th and 16th governor of Ohio, United States minister to Mexico, U.S. congressman, and the second territorial governor of Kansas. He was a leading proslavery figure in early Kansas politics and, despite a short 9.5-month tenure, its longest continuously-serving territorial governor. Despite these successes, the disastrous violence of "Bleeding Kansas" began during his term as territorial governor.

Shannon was born on February 24, 1802, in what is now Belmont County, in southeastern Ohio. His father was a Revolutionary War veteran of Irish descent. Orphaned and raised by two older brothers, Shannon was nonetheless educated at two of the West’s first colleges, Ohio University in Athens and Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky, where he studied law. In 1826 he began his own legal practice in his hometown of St. Clairsville.

A Democrat, Shannon quickly gained repute in local politics. In 1832 he was nominated as a candidate for Congress, but the Whig Party nominee defeated him by 37 votes. Far from defeated, Shannon went on to serve as Belmont County’s prosecuting attorney from 1833 to 1835, and was elected governor of Ohio in 1838, defeating Whig Joseph Vance. He was beaten in his 1840 bid for reelection by conservative Whig Thomas Corwin, but went on to defeat Corwin and serve another term in 1842. Shannon resigned during his second term as governor after being named minister to Mexico by President James K. Polk. Although he only served as minister for one year, it was a significant appointment, as the two nations were on the brink of a boundary dispute in 1844 that would eventually lead to full-scale war. Scholars have since deemed Shannon’s performance as minister an overall failure.

Shannon returned to his home state—this time to Cincinnati—to practice law after his disappointing tenure as minister. Like tens of thousands of other Americans, he caught “gold fever” in 1849 and moved to California before soon returning to Ohio. After several years of civilian life, Shannon itched to get back into politics, and in the fall of 1852 he was elected to the United States Congress, where he served a single term. He proved a moderate proslavery voice, supporting the Democratic policy of “popular sovereignty” and Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas’s Kansas-Nebraska Act. With Shannon’s credentials as a moderate Democrat fully established, President Franklin Pierce appointed Shannon governor of Kansas Territory on August 10, 1855. Shannon replaced Democrat Andrew H. Reeder, who was dismissed after taking a firm stance against what he deemed a corrupt proslavery faction in Kansas. Given Shannon’s firmer proslavery credentials, Kansas and western Missouri slaveholders anticipated that Shannon would prove to be a political ally.

Shannon was sworn in as governor on September 7, 1855, and his time in office marked an upswing in political violence throughout Kansas. The “Wakarusa War” of that December led to a series of violent reprisals. Shannon’s reputation as a Northerner with generally proslavery sympathies was solidified by his use of federal troops at Fort Riley and Fort Leavenworth to support the proslavery agenda.

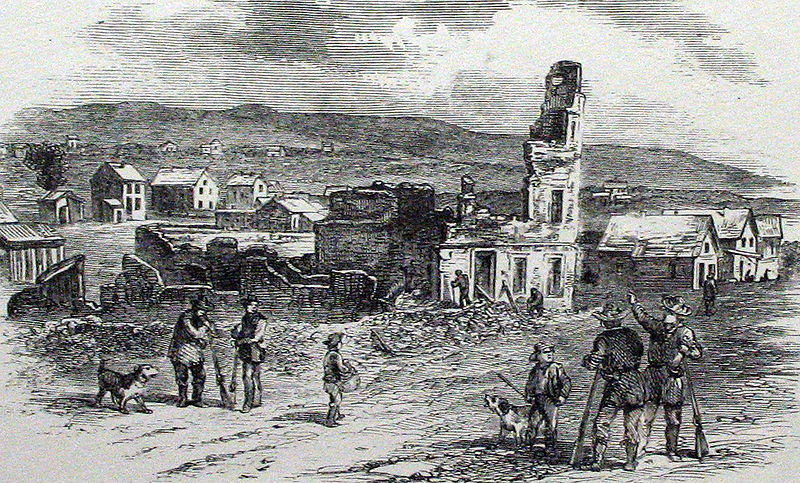

Shannon’s lack of response to the Sack of Lawrence on May 21, 1856, upheld his proslavery reputation. The leaders of the raid wanted to retaliate for the shooting of a proslavery public official and hoped to disarm the Free-State militia in Lawrence. They led roughly 800 proslavery men armed with cannon against the antislavery town of Lawrence and destroyed two antislavery presses and the Free-State Hotel, which had been built as a de facto Free-State fortification. Although there was only one casualty amid the destruction and looting, Shannon’s response was strikingly inert. His inaction contributed to Free-State reprisals. One probable act of retribution was the infamous Pottawatomie Massacre of May 24-25, in which militant abolitionist John Brown and his small band of “Pottawatomie Rifles” hacked five proslavery men to death with broadswords in Franklin County. Shannon soon lost control of the territory and, fearing for his life, left for St. Louis, Missouri, on June 23. Shannon attempted to submit his resignation, but was at last officially removed from office by President Pierce on August 18, 1856, and replaced by John W. Geary. In sum, Shannon served in office for over nine months, the longest continuous tenure of any Kansas territorial governor.

Shannon’s lack of response to the Sack of Lawrence on May 21, 1856, upheld his proslavery reputation.Following his firing, Shannon reentered his old trade, setting up a law office in the proslavery town of Lecompton, Kansas, before practicing law in both Topeka and Lawrence. The first county seat of Anderson County (now abandoned) was named in his honor, and for the next two decades he was a well-known and successful attorney. Although scholars have since deemed Shannon a tactless politician and, in the words of historian James A. Rawley, a “poor appointment” for such a sensitive position, he nonetheless defended his policies as governor later in life by likening governing territorial Kansas to governing “the devil in hell.” Shannon died on August 30, 1877, in Lawrence.

Suggested Reading:

Etcheson, Nicole. Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004.

Nichols, Alice. Bleeding Kansas. New York: Oxford University Press, 1954.

Rawley, James A. Race & Politics: "Bleeding Kansas" and the Coming of the Civil War. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1969.

Socolofsky, Homer E. Kansas Governors. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1990.

Cite This Page:

Stanley, Matthew. "Shannon, Wilson" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Wednesday, April 24, 2024 - 00:01 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/shannon-wilson