By Tony O’ Bryan, University of Missouri – Kansas City

Although the name “Red Legs” is commonly conflated with the term “jayhawkers” to describe Kansas guerilla units that fought for the Free-State side during the Bleeding Kansas era or the Union side in the Civil War, Red Legs originally referred to a specific paramilitary outfit that organized in Kansas at the height of the Civil War. Union Generals Thomas Ewing, James Blunt, and Senator James H. Lane were all supporters of the group, and Kansas Governor Thomas Carney personally financed it for service. The Red Legs first joined together near Atchison, Kansas, under the command of Charles R. “Doc” Jennison and Captain George H. Hoyt, a Massachusetts lawyer who defended John Brown at his trial after the Harpers Ferry Raid. The men who joined the group called themselves the Red Legged Scouts and their stated purpose was to serve as scouts and spies for the Union Army. The Red Legs were never officially mustered into the Union Army and there are no formal unit histories; however, their deeds along the border became notorious among Missourians and notable among Kansans.

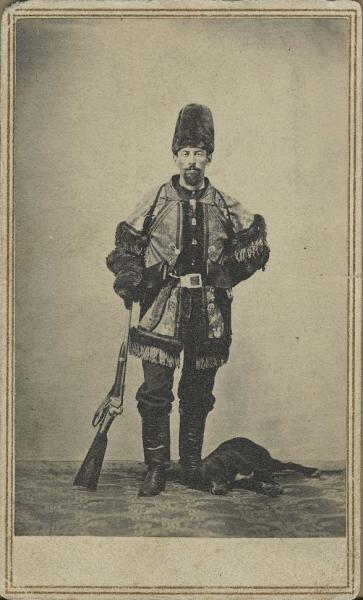

The Red Legs were a somewhat secretive organization of about 50 to 100 ardent abolitionists who were hand selected for harsh duties along the border. Membership in the group was fluid and some of the men went on to serve in the 7th Kansas Cavalry or other regular army commands and state militias. They are associated with a lesser-known group that called themselves the “buckskin scouts,” and they served as an auxiliary arm to regular troops, such as the 6th Kansas Cavalry on punitive expeditions into Missouri. The legendary James “Wild Bill” Hickok, then still just a teenager, William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, and fellow Pony Express rider William S. Tough are among the few individuals known to have served with the Red Legs. Buffalo Bill Cody admitted that as a member of the Red Legs, “We were the biggest thieves on record.”

Buffalo Bill Cody admitted that as a member of the Red Legs, “We were the biggest thieves on record.”

There are several versions of the story of how they earned the name and their reputations along the Missouri-Kansas border. One account of the legend claims that the men chose to wear tan or red colored yarn leggings to both distinguish themselves as a unit and to protect their legs while riding and marching through thick brush. Two stories from the Missouri side of the state line claim that in 1861, when Jennison and Hoyt led these men into Independence, Missouri, declared martial law, and forced the citizens to swear loyalty oaths, they also raided a local store and stole rolls of red carpet that they cut into strips to make a covering for their legs. Some Missourians claim the Red Legs stole red draperies and bolts of cloth from people’s homes and used that material to make their distinctive red leggings. In another tale, the men stole from a cobbler’s shop a supply of sheep hides that had been dyed red and precut to make boot tops. There is likely a grain of truth in all of these origination tales. Over the course of the war other groups of anonymous brigands from Kansas also wore red leggings on their raids into Missouri, much to the chagrin of a succession of Union Army commanders, who were charged with keeping peace and order along the border.

The Red Legs accompanied Jim Lane and the jayhawkers on a raid through Butler, Harrisonville, Clinton, and Osceola, Missouri, in September 1861, which left those towns and the farms along the way in a smoldering swath of ruin. When not raiding into Missouri, they patrolled for bushwhackers who made raids into Kansas. They held headquarters in Lawrence, Fort Scott, and at Six-Mile House on the road to Fort Leavenworth from Quindaro, Kansas. When a band of Missourians rode into Kansas to track down their stolen livestock, the Red Legs rounded them up and several Missourians were hanged. Illegal raids by the Red Legs eventually led Blunt to disavow them and all other paramilitary groups that defied legal authority. When Kansas Governor Charles Robinson—himself an ardent Unionist and supporter of the Free-State cause—tried to have the disruptive forces of the Red Legs removed from the region, they attempted to assassinate him in retaliation. These events prompted both Governor Robinson and Missouri Governor Hamilton R. Gamble to complain about the anarchy and cruelty caused by the actions of the Red Legs in letters to President Lincoln.

In the late winter and spring of 1862, the Red Legs raided across southern Jackson County, Missouri, burning homes, slave cabins, and stealing livestock. They reached as far east as Columbus, Missouri, in Johnson County, where they burned the town to the ground and encouraged untold numbers of slaves to follow them back to Kansas along their way. In March 1863, they and the 1st Colored Infantry drove across Jackson County and into Lafayette County, Missouri, areas that held the largest slave population in the state on the eve of the war. They burned the college town of Chapel Hill, Lafayette County, and again emancipated a number of slaves who followed the Red Legs and the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry back to Kansas. Because the Red Legs were avowed abolitionists and suspected all Missourians of supporting slavery, as well as harboring the bushwhackers, they killed several local men despite the fact that these men had previously sworn loyalty oaths to the Union.

When Quantrill and his gathered bands of bushwhackers attacked Lawrence, Kansas, on August 16, 1863, they cited the deeds of the Red Legs as their motive for their attack on the town. One of the first targets of the bushwhackers was the headquarters of the Red Legs, the Johnson House Hotel, and they held lists with the names and residences of men known to ride with the Red Legs. They quickly surrounded the hotel and proceeded to burn it down and shoot any man suspected of being a Red Leg. After the attack on Lawrence, General Ewing issued Order No. 11, in part to prevent the promised revenge upon Missourians along the border by the Red Legs and jayhawkers led by Jim Lane. The order evacuated the remaining Missourians along the border counties who had not already been driven away by the actions of the Red Legs, jayhawkers, Union Army, and the bushwhackers.

Several Red Legs can be seen in George Caleb Bingham’s provocative painting, Martial Law, (or Order No. 11). Two of them are dressed in the customary red leggings, plumed hats, Union long tunic coats, and armed with pistols about their waists. Two more can be seen carrying loot on horseback, with one of them carrying a picnic basket and others loading furnishings onto a wagon from a second story balcony. The Red Legs made a final appearance at the Battle of Westport, inside the boundaries of modern-day Kansas City, Missouri, where they helped defeat General Sterling Price’s 1864 Missouri Expedition. The Red Legs faded from the scene afterwards as guerilla war diminished along the border, and “Doc” Jennison was court martialed and dismissed from service in June 1865. Even after 150 years, though, the deeds of the Red Legs are not forgotten on either side of the state line.

Suggested Reading:

Gilmore, Donald L. Civil War on the Missouri-Kansas Border. Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Co., 2006.

Nichols, Bruce. Guerrilla Warfare in Civil War Missouri Volume II. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. Publishers Inc., 2012.

Peterson, Paul R. Quantrill at Lawrence: The Untold Story. Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Co., 2011.

Cite This Page:

O'Bryan, Tony. "Red Legs" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Tuesday, April 23, 2024 - 03:30 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/red-legs