By Marc Reyes, University of Connecticut

Constitution Summary:

- Date originally drafted: February 1858

- Stance on slavery: prohibited

- Suffrage for women: none

- Suffrage for African Americans: for males only

- Suffrage for Native Americans: none

- Status: failed to be ratified by the U.S. Senate in May 1858

In just 57 words, the Leavenworth Constitution, first drafted in February 1858, boldly guaranteed all the power and protection of American citizenship to men of all races:

All men are by nature equally free and independent, and have certain inalienable rights, among which are those of enjoying and defending life and liberty, acquiring, possessing, and protecting property, and seeking and obtaining happiness and safety; and the right of all men to the control of their persons exists prior to the law, and is inalienable.

With language echoing the Declaration of Independence, the future state of Kansas considered the unprecedented measure of extending equal rights of citizenship to black males. Serving as an early example of Brandeisian thinking, wherein states, or in this case a territory, function as “laboratories of democracy,” the delegates who gathered in Leavenworth, Kansas, placed the enfranchisement of black males up for consideration a full decade before the federal government enacted the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Through the drafting of the Leavenworth Constitution, one territory crafted a guiding state charter promising the abolition of slavery, freedom of speech, freedom of worship “to the dictates of their own conscience,” and freedom to all men regardless of skin color.

In the years before the official start of the American Civil War, Kansas Territory received an early vision of the bloodshed of the Civil War. The mayhem of the “Bleeding Kansas” era was more than a violent struggle over the expansion of the institution of slavery, as the animosity of the period boiled over into political and legal debates. This was especially apparent when the territory prepared for statehood as the tasks of creating, approving, and receiving federal recognition of Kansas’s founding document were proving an impossible feat.

By 1858 Kansas Territory had spent three years trying to produce a state constitution that could win the support of Kansans as well as the U.S. Congress. The Topeka Constitution, proposed in 1855, won local support, but its promise to ban slavery in the future state of Kansas only guaranteed passage in the U.S. House; the U.S. Senate refused to bring the measure to a vote. Two years later the proslavery Lecompton Constitution received the endorsement of President James Buchanan but provoked a vicious backlash among Free-State advocates. Seething at the audacious power grab undertaken by Kansas slave owners, antislavery activists boycotted the vote for ratification of the second attempted constitution. Once again the territory of Kansas was without an official charter and went back to the constitutional drawing board for a third time.

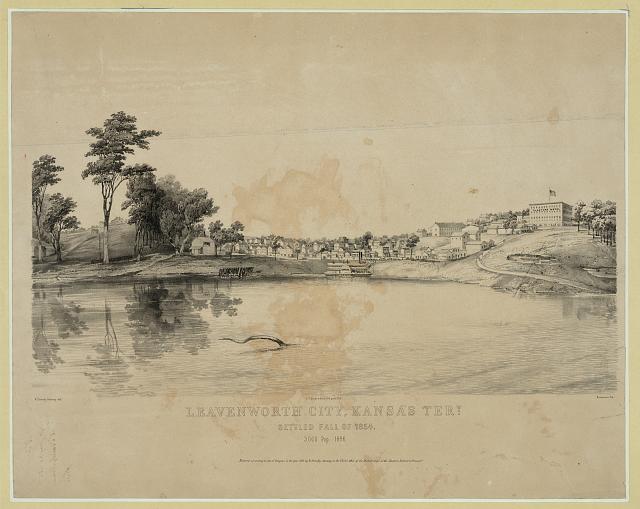

To the town’s fervid abolitionists, the ones inspired by John Brown and his war against slavery, previous documents like the Topeka Constitution contained too many compromises.Even before the death of the Lecompton Constitution, Kansas Free-Staters gathered in the proslavery town of Leavenworth to produce a different kind of constitution. Despite the town’s noticeable proslavery stance and the fact that Leavenworth was where the proslavery Law and Order Party had been established, a number of fervent abolitionists also called the town home. These advocates against slavery found outlets for their principles by creating secret passages to transport slaves to freedom through the Underground Railroad and also went a step further by naming the most racially progressive of Kansas’s four proposed constitutions after the proslavery town. To the town’s fervid abolitionists, the ones inspired by John Brown and his war against slavery, previous documents like the Topeka Constitution contained too many compromises. In particular, the Topeka Constitution’s “exclusion clause,” which would have evicted all blacks already residing in Kansas, was too much to stomach. For Free-Staters who were motivated against the evils of slavery and who saw a slave as a human being instead of property, the delegates who arrived in Leavenworth sought a different path for their future state.

The assembled delegates who arrived at the Leavenworth convention came from different backgrounds, but many had been propelled by deep religious convictions to leave abolitionist strongholds, especially Massachusetts, and head west to Kansas to stop the spread of slavery. Delegates Charles Foster and Convention Secretary Samuel Tappan both left the east coast and became involved in the Free-State movement. Like Foster and Tappan, delegates Charles and Sara Robinson came from strong abolitionist families and left comfortable livelihoods to ensure that the state of Kansas entered the Union as a free state.

Instead of revising the Topeka Constitution, the drafters of the Leavenworth Constitution started from scratch and drafted a broader vision of equality that incorporated much of the Free-State agenda. Besides ending slavery and expanding citizenship to black males, the constitution promoted an official state college, a public school system, and plentiful and affordable land to thousands of settlers seeking a better life.

As proud as Leavenworth constitutional delegates were with the final draft of the constitution, their victory was ultimately short-lived. Despite being progressive on racial issues, it did not encompass all Free-Staters’ beliefs. Delegates like Charles Robinson, a future governor of Kansas, advocated that suffrage be extended to women and Native Americans but watched as the convention voted down the measure and continued to define citizenship to a limited section of the population. Even with these compromises, such a forward-thinking vision of greater racial equality was unlikely to pass in the U.S. Senate, a legislative body where Senator Charles Sumner had been violently beaten for criticizing slave owners and delivering an antislavery speech just two years before.

May 1858 was a pivotal month for the Leavenworth Constitution. In the same month that Kansas voters ratified the Leavenworth Constitution, the U.S. Congress also rejected it. Its supporters were not surprised by the outcome, and Kansans would have to take another stab at a state constitution. Still, the delegates behind the Leavenworth Constitution showed considerable foresight. Ten years later, Radical Republicans in the U.S. Congress made the rights promised to black men a reality with the 1868 passage of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which finally delivered what Free-Staters originally advocated in the little Kansas town of Leavenworth.

Suggested Reading:

Cutler, William G., A.T. Andreas, and Thelma Carpenter. History of the State of Kansas, containing a full account of its growth from an uninhabited territory to a wealthy and important State... Also, a supplementary history and description of its counties, cities, towns, and villages.... Chicago: A.T. Andreas, 1883.

Heller, Francis H. The Kansas State Constitution: A Reference Guide. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1992.

Robinson, Charles. The Kansas Conflict. New York, NY: Harper & Brothers, Franklin Square, 1892.

Wilder, Daniel W. The Annals of Kansas. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1875.

Cite This Page:

Reyes, Marc. "Leavenworth Constitution" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Wednesday, April 24, 2024 - 21:25 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/leavenworth-constitu...