By Matthew E. Stanley, Albany State University

Event Summary:

- Date: May 21, 1856

- Location: Lawrence, Douglas County, Kansas

- Adversaries: Free-Staters vs. proslavery militia

- Casualties: One Proslavery man killed

- Result: Proslavery attackers dispersed, with most returning to Missouri

The First Sack of Lawrence occurred on May 21, 1856, when proslavery men attacked and looted the antislavery town of Lawrence, Kansas. The assault escalated the violence over slavery in Kansas Territory during a period that became known as “Bleeding Kansas.” The sacking coincided with South Carolina congressman Preston Brooks’s scandalous caning of abolitionist Republican senator Charles Sumner, which had occurred on May 20. The two events were paired and dramatized by the national media, constituting turning point in the lead up to the Civil War.

Lawrence, Kansas, was founded in 1854 by the New England Emigrant Aid Society with an antislavery mission, and named after Boston philanthropist and antislavery reformer Amos Lawrence. Established on the heels of 1854’s Kansas-Nebraska Act, Lawrence developed during a period of increasing tension in the Kansas Territory between newly-arrived eastern abolitionists and proslavery southerners, particularly border Missourians. The aid movement made considerable headlines in the eastern press during 1854, and Lawrence’s founders nearly battled with proslavery Missourians in October of that year. Political strain intensified throughout 1855 following the Big Springs resolutions, the creation of a Free-State Party, and the Wakarusa War that fall. By late 1855, Lawrence residents fully anticipated an attack by proslavery partisans or “border ruffians” (the pejorative term for proslavery Missourians who crossed the state line to commit voting fraud or political intimidation). Indeed, that December agents from the Emigrant Aid Society requested additional weapons—Sharp’s rifles (“Beecher’s Bibles”) and cannon—from their eastern benefactors as approximately 1,200 proslavery men, mostly Missourians, assembled on the Wakarusa River. With Lawrence besieged, only executive intervention by Governor Wilson Shannon staved off violence. But a harsh winter and snowballing political tension ensured that a proslavery attack had been more delayed than prevented.

Conditions were ripe for conflict when ... Douglas County Sheriff Samuel J. Jones was shot in the back while attempting to arrest some Free-State men on April 23.

The 1856 spring migration of antislavery settlers indicated that time was on the side of the Free-Staters. Lawrence, by now the center of crusading antislavery activity in Kansas, was growing, and proslavery forces felt a sense of urgency to suppress perceived antislavery insolence. Conditions were ripe for conflict when Wakarusa War veteran and Douglas County Sheriff Samuel J. Jones was shot in the back while attempting to arrest some Free-State men on April 23. Although only wounded, Jones was reported dead by the proslavery press and its disciples vowed revenge on the town. Although the antislavery press censured the attack, Judge Samuel D. Lecompte urged a territorial grand jury indict a number of Free-State officials and deemed their newspapers and hotel threatening to the peace. On May 11, federal marshal I. B. Donaldson issued a proclamation asking territorial citizens to aid him in serving warrants in Lawrence against the extralegal Free-State legislature. Donaldson was joined by at least a half dozen proslavery militia units, including the Douglas County Militia, the Kickapoo Rangers, and the Missouri Platte County Rifles, and peacefully made his arrests. Yet in response to Donaldson’s mobilization and the findings of a territorial grand jury that antislavery forces in Lawrence were militarizing, Sheriff Jones assembled roughly 750 men to enter the town, disarm its citizens, and destroy its antislavery institutions.

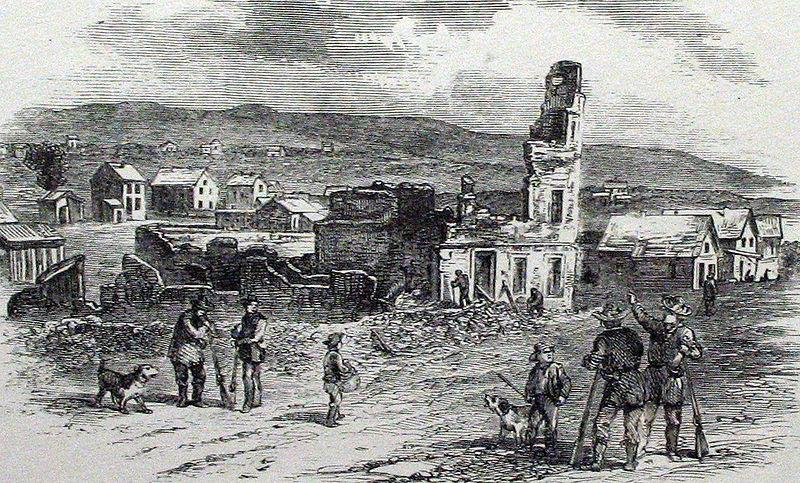

On May 21, Jones’s men placed cannon on nearby Mount Oread, sealed off all possible escape routes, and approached the town. With their leaders under arrest, the citizens of Lawrence offered no resistance. Rather than chaotic and irrationally violent, the proslavery attack was calculated and political. Donaldson made his headquarters in the residence of Dr. Charles Robinson, an antislavery leader and future first governor of the state of Kansas who was then under arrest at Lecompton. The proslavery force next targeted both of Lawrence’s antislavery newspapers, including raising a banner with “Southern Rights” inscribed on one side and “South Carolina” on the other atop the printing office of the Herald of Freedom. The printing presses of both the Herald and The Kansas Free-State were then thrown into the Kansas River. The Free-State Hotel, which the proslavery grand jury claimed was in fact a military fortress, next drew the ire of the mob. Built by the Emigrant Aid Society, the stone hotel was blown up, ransacked, and burned. Attackers also directed violence and robbery against the homes of prominent abolitionists. The crowd then dispersed, with most returning to Missouri. For all its destruction, the incident produced only one casualty, a proslavery man who was killed by a falling brick.

Built by the Emigrant Aid Society, the stone hotel was blown up, ransacked, and burned.

The Republican press quickly labeled the attack the “Sack of Lawrence,” and it created a media firestorm in the North. Antislavery newspapers circulated false reports that Free-State persons had been killed, and many otherwise neutral Americans admired the control exhibited by the antislavery faction and sympathized with their loss. Although the proslavery press downplayed the event as abolitionist sensationalism, the Sack of Lawrence, together with the caning of Charles Sumner, confirmed Republican fears of a violent “Slave Power” conspiracy. After all, a territorial grand jury, a county sheriff, a U.S. marshal had fomented the clash. Free-State restraint was short-lived, as militant abolitionist John Brown was so aroused by the Lawrence-Sumner bulletin that he retaliated by killing five proslavery men on May 25, 1856, in what became known as the Pottawatomie Creek Massacre.

Violent events in Kansas increasingly dictated policy in Washington. As South Carolina Congressman Lawrence Keitt wrote after the event, “The Kansas fight has just occurred and times are stirring. Everybody here feels as if we are on a volcano.” “Bleeding Kansas” became a major campaign issue in the fall of 1856, the first to feature a Republican presidential candidate, prefiguring at the territorial level increasingly national political division and sectional conflict. Still more violence befell Lawrence during the Civil War, as Confederate guerrilla William Clarke Quantrill and his raiders attacked the town on August 21, 1863, in what became known as the Lawrence Massacre.

Suggested Reading:

Etcheson, Nicole. Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004.

Rawley, James A. Race & Politics: “Bleeding Kansas” and the Coming of the Civil War. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1969.

Cite This Page:

Stanley, Matthew. "First Sack of Lawrence" Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library. Accessed Thursday, April 18, 2024 - 19:30 at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/first-sack-lawrence