- Type: Pamphlet

- Date: 1864

- Significance: Alleges that Missouri bushwhackers committed various atrocities against Union soldiers, suggests remedies

- Owning organization: St. Joseph Public Library

- Related Topics: William Clarke Quantrill, Hamilton R. Gamble, Bushwhackers, Platte Bridge Railroad Tragedy, Burning of Platte City, Quantrill's Raid on Lawrence, First Battle of Lexington, Abraham Lincoln, Sterling Price, Joseph O. Shelby, Claiborne Fox Jackson, Samuel R. Curtis

By Jason Roe, Kansas City Public Library

The Featured Document Blog places the past in your grasp by introducing a compelling item from our digital collection.

Sign up for our newsletter, This Month in the Civil War on the Western Border »

Major J.M. Bassett, former Provost Marshal-General of the Northwest District of Missouri, authored this vitriolic pamphlet in hopes of raising money to support the state's Union soldiers and their families. He denounced the actions of Confederate bushwhackers in northwestern Missouri from the earliest days of the war to 1864. Among the stories outlined in the pamphlet—some accurate, others undoubtedly embellished—were accounts of plunder, the collapse of law and order, conspiracy, torture, murder, and mutilation of prisoners' bodies.

Near the beginning of the pamphlet, Bassett acknowledged that he did not intend to present an objective viewpoint. He lamented that pro-Confederate sentiments nearly took over in Missouri at the outset of the war, starting with Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson's secessionist actions. From Bassett's perspective, secessionists had free rein while a minority of "armed traitors" intimidated the majority of Unionists into silence, eliminating free speech statewide. He alleged that the rebels "desired to see a time when the blood of Union men would redden the streets."

Bassett described several prominent events, including secessionists seizing the United States Arsenal at Liberty on April 20, 1861, and the Platte Bridge Railroad Tragedy of September 3, wherein Missouri bushwhackers undermined the structure of a bridge on the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad. The bridge collapse caused a derailment that killed up to 20 passengers and disrupted freight and mail for some days. Bassett hurled insults at those who would commit "treason," writing, "Yet in our State it is a fashionable offense, and its votaries are claimed by a sort of depraved, velvet-pawed feline class of politicians, as persons who are peculiarly fitted to assist in controlling the civil and military affairs of the State."

By design, this account omitted atrocities committed by Union forces, jayhawkers, or Red Legs, but it does provide a window into the intensity of violence and an outspoken, partisan Unionist viewpoint. Bassett largely dismissed any Union-instigated outrages as necessary acts of retaliation or self-defense against the rebellion. He did not directly name such events as General Order No. 11, the Sacking of Osceola, or the Raid on Dayton. On the other hand, his description of pro-Confederate atrocities grew more vivid by the end of the pamphlet.

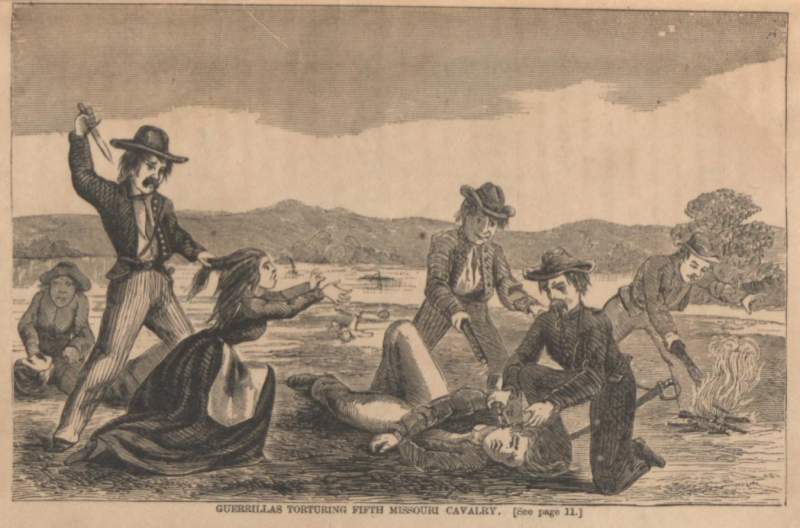

In one of his more dramatized passages, Bassett described the actions of a band of guerrillas who captured five men from the 5th Cavalry Regiment of the Missouri State Militia, from Jackson County:

Their captors cut off their ears, and mutilated their bodies in a manner too shocking for belief. Still these soldiers lived, and to the great delight of the rebels, were conscious of their sufferings. These prisoners were then laid down and their bodies again tortured—the fiends filled their ears with powder, and with live coals flashed it off. In vain the victims prayed for the mercy of instant death. They were only answered by curses. The torturing process was again repeated.

This sequence of events from the incident cannot be confirmed, but official Union reports stated that the victims' bodies were found with missing ears and signs of torture. Quantrill's Raiders and other bushwhacker groups were known to kill captured Union soldiers on the spot, and William T. Anderson similarly gained his cognomen, "Bloody Bill," for similar atrocities. On the other side, Union policy after the early parts of 1862 was not to grant quarter to Missouri guerrillas, and the 5th Cavalry in particular established a reputation for killing bushwhacker prisoners and occasionally Southern sympathizers who had not directly taken up arms.

Bassett's account, of course, did not acknowledge that the violence had escalated on both sides, only suggesting that the Union had been too soft on the guerrillas. He continued to describe secret Confederate organizations, a planned raid into Missouri by Major General Sterling Price (which incidentally would be carried out within the publication year of this pamphlet), and William Clarke Quantrillh's Raid on Lawrence.

The pamphlet moved toward a conclusion with Bassett revisiting the suffering of Union soldiers and their families:

More than sixty thousand Union men in Missouri have enlisted to assist in the putting down of this rebellion. The soil of nearly every battlefield in the Mississippi valley covers the bones of many of these brave soldiers, "Who have slept their last sleep, And have fought their last battle." We see their destitute widows, ragged and hungry orphans, every day in the streets of our cities.

In the remaining pages, Bassett outlined his argument that the only way to relieve suffering in Missouri would be to emancipate its slaves, which presumably would eliminate the Confederacy's claim to Missouri as a member a state. He pointed out that the Union already compensated slaveholders for the military service of their young male slaves and that the market value of all other slaves had plummeted due to uncertainty about the future of the institution of slavery itself. Bassett reasoned that the state government could purchase the remaining slaves, emancipate them, and reduce internal tensions in the state while preventing a Confederate invasion of the state.

Of course, the future that Bassett envisioned did not come to pass. Missouri did not formally abolish slavery until January 11, 1865, and it is unlikely that emancipating slaves would have dissuaded Major General Sterling Price from leading a massive cavalry raid across the state of Missouri in September and October of 1864. The intense hatred and tragic violence of the war in Missouri only cooled in the years and decades after the conclusion of the Civil War.