Summary:

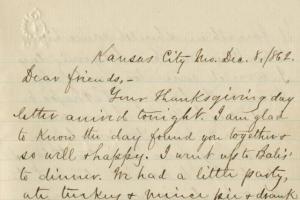

- Title: From John C. Gage to Dear Friends

- Type: Personal correspondence

- Date: December 8, 1862

- Author: John C. Gage

- Significance: Account of the war in and around Kansas City in the fall of 1862

- Owning Organization: Jackson County Historical Society

- Related History: Jayhawkers; James H. Lane; Charles R. Jennison; 1st Kansas Colored Volunteers

By Jason Roe, Kansas City Public Library

The Featured Document Blog places the past in your grasp by introducing a compelling item from our digital collection.

John C. Gage, a resident of Kansas City, Missouri, and a lawyer by trade, was anything but thankful in the weeks following the Thanksgiving of 1862. His letter of December 8, 1862, addresses friends in Pelham, New Hampshire, and in it and a preceding letter, Gage complains of attacks from Kansas “jayhawkers,” especially James H. Lane and Charles “Doc” Jennison, on the civilian populations of Missouri. The December letter begins warmly enough, with Gage referencing a “little party” for Thanksgiving and a dinner that included such timeless staples as turkey, mince pie, and champagne.

From there his note descends into a description of the hardships of the war for him and everyone else. His dog, a pointer, was shot earlier in the same day that he wrote the letter, and he was unsure of whether it would survive.

Gage goes on to mention that he lost a black servant, who left without warning and may have stolen “something” from him. Toward the end, Gage writes,

We think nothing of it when a man from our very side almost is killed in battle. It is in the common course of things for anybody to get killed. Their own families hardly seem to mourn for them . . . The cripples can be seen continually about the streets with their crutches.

A previous letter from John Gage to his friends in New Hampshire, dated September 1, 1862, offers more details about life in Kansas City in the fall of that year. As a member of the militia, Gage describes being called to defend the city over fears of pro-Southern guerrilla raids from the Missouri bushwhacker William Clarke Quantrill. But Gage saves his harshest criticism for “Jim Lane’s negro brigade under Jennison,” which was a probable reference to the newly established 1st Kansas Colored Volunteers. Although officially parts of the Union Army, Lane and Jennison’s forces often exceeded their legal mandates to raid Missouri farms and liberate slaves, as well as sack towns known to be associated with proslavery guerrilla “bushwhackers.”

Ominously, Gage also heard a rumor that Jennison was planning to march on Kansas City, and “Jennison threatens to hang 50 men within three hours after he gets here and I think it probable that I stand as low as anybody in his estimation.” While Gage and Jennison both fought on the federal side, Gage despised Jennison's guerrilla tacts and even went so far as to write, “He [Jennison] ought to be killed and I would esteem it the best act of my life to do it.” John C. Gage did not follow through on his threat to kill Charles R. Jennison, who survived the war and died of natural causes in 1884.

Historically, 1862 was the last year that Thanksgiving was celebrated on varying dates in the Northern states. In an attempt to promote cultural unity between the North and South, President Abraham Lincoln proclaimed that the Thanksgiving of 1863 would be held on the last Thursday of every November. The Northern states celebrated their first federally recognized Thanksgiving in 1863, while the Southern states observed the federal holiday only in the years following the Civil War.

Additional Resources

Baker, James W. Thanksgiving: The Biography of an American Holiday. Durham, NH: University of New Hampshire Press, 2009.

Neely, Jeremy. The Border Between Them: Violence and Reconciliation on the Kansas-Missouri Line. Columbia London: University of Missouri Press, 2007.

O'Bryan, Tony. "Jayhawkers." Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1854-1865. The Kansas City Public Library.