- Type: Letter

- Date: January 10, 1855

- Location: Wyandotte County, Kansas

- Owning organization: Baker University Archives

- Topics referenced: Bleeding Kansas, Border Ruffians, Popular Sovereignty

By Jason Roe, Kansas City Public Library

The Featured Document Blog places the past in your grasp by introducing a compelling item from our digital collection.

Sign up for our newsletter, This Month in the Civil War on the Western Border »

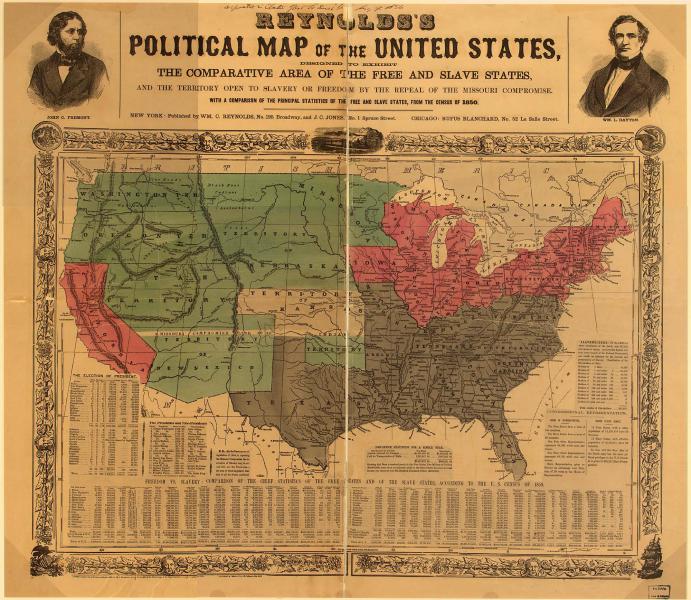

Within months of the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act on May 30, 1854, white settlers began streaming into Kansas Territory. With the new law in place, the decision about whether Kansas would enter the Union as a slave or free state rested not with the U.S. Congress, but instead with the local representatives elected by the residents of Kansas. These developments sparked a race between proslavery and antislavery factions to bring in as many settlers who were sympathetic to their side as possible. Nationally, the stakes were high; the addition of a new state on either side could disturb the delicate balance between free and slave states that had been maintained through a series of compromises in the previous decades. Accusations of fraud swirled from the earliest territorial elections.

Among the early waves of white settlers to Kansas was James Griffing, who wrote this letter in a cross-hatched style from the settlement of Wyandotte in Wyandotte County, Kansas, and sent it to an unknown recipient. Griffing, from Owego, New York, sided with the Free-Staters and admired those who chose to live in primitive conditions in Kansas despite being "permitted from the circumstances in which they were placed to enjoy the first of society." Early in his letter, he stated that two-thirds of Kansas residents were in favor of the free state cause, even though the "late election," on November 29, 1854, did not go in their favor. That first territorial election sent a proslavery delegate to Congress after "border ruffians" from Missouri crossed into Kansas to fraudulently cast their ballots or intimidate antislavery voters. In subsequent letters, including one from April 1855, Griffing continued to complain of election fraud from the notorious elections of March 30, which resulted in the so-called "Bogus Legislature." In that election, the town of Leavenworth recorded five times more proslavery votes than its entire population. In the following years, election fraud escalated into violence instigated by partisans on both sides of the Missouri-Kansas border, making individuals such as John Brown and David Rice Atchison household names on a national scale.

As of January 1855, though, the term "Bleeding Kansas" had not yet been coined, and James Griffing brushed off concerns about the first territorial election. He wrote that Missourians were more dangerous than American Indians, but advised that "there is no more reason for a person who attends to his own business to be afraid here than anywhere under the broad canopy of the universe." After the first territorial election, he believed the antislavery settlers needed to "assert their rights and strive to maintain them."

For the earliest white settlers to Kansas, predictions of a Civil War were years away, and they concerned themselves mostly with making a home in the territory. Griffing's letter described some of the conditions, saying they were "surrounded entirely by Indians." This was true in January 1855, but in the next few years the federal government placed Delaware, Shawnee and other tribes' lands up for sale and removed the Kansas tribes to Indian Territory (modern Oklahoma). Griffing continued to explain that he was in the process of building a square, 15-by-15 feet cabin. He could purchase glass for windows at Lawrence, Kansas, but he did not mention other amenities. Surprisingly there had been no snow, and he considered the Kansas weather to be mild.

Overall, Griffing remained optimistic about Kansas. He described dozens of neighbors—mostly Yankees—within a half hour walk, and he predicted that in less than a year he "may count twenty cabins from our doors." In contrast to other accounts from the period, Griffing described pioneering life in an almost quaint manner and dismissed any concerns about impending violence and political strife. It should be remembered, though, that other correspondence made it clear that Griffing actively encouraged others to migrate from the Northeast and live in Kansas, suggesting that his account may have included an ulterior motive. Reading between the lines, James Griffing's letter subtly referenced the salient issues that would soon lead to Bleeding Kansas and eventually spark the American Civil War.