Illustration of Jefferson Davis imprisoned at Fort Monroe, Virginia. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

By Jason Roe, Kansas City Public Library

In the spring of 2015, the Library commemorates the sesquicentennial of the final months of the Civil War in Missouri and Kansas with a post derived from the thousands of primary sources that are digitized and incorporated into this website. The Library and its project partners collaborated to assemble this rich repository from the collections of 25 area archives, combining it with interpretive tools and original scholarship produced by nationally recognized historians.

Downfall of the Confederacy

With the Confederacy’s military capacity all but destroyed and its government on the run from advancing Union forces, May 1865 began with the opening of a military tribunal on the first of the month. Set up by orders of President Andrew Johnson, the tribunal’s purpose was to try eight prisoners suspected in the conspiracy to assassinate President Abraham Lincoln the previous month. Several months later, all of them stood convicted, and four died at the gallows. As the conspirators’ fates were being decided, the Confederate government and its remaining military forces continued their collapse, and the long, bloody Civil War finally ground to a halt.

In the previous month, one day before the cities of Richmond and Petersburg, Virginia, fell on April 3, 1865, Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his cabinet fled the capital city by rail and reconvened in Danville in south-central Virginia. Less than a week later, the surrender of Major General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox Court House on April 9 caused most Southerners to admit that the war was at an end. Rather than laying down arms upon receiving word of Lee’s capitulation, as many Confederate commanders would soon do, Davis and his cabinet vowed to continue fighting and fled again to Washington, Georgia. By the end of the month, General Joseph E. Johnston had surrendered the Army of Tennessee and all other forces under his command in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. Although skirmishes and paramilitary activity would continue, large-scale Confederate military resistance promptly ended after Appomattox.

At the beginning of May 1865, a few Confederate commanders and political leaders, including Davis, still called on Confederates to continue the fight through means of guerrilla warfare. Most Confederates followed the lead of General Lee, who rejected the idea because he saw it as pointless, needlessly destructive for the South, and likely to ruin any opportunity for peaceful reconciliation between North and South. Rather than divide his Army of Northern Virginia so that elements of it could escape Grant’s grasp—which would result in it breaking up into “bands of marauders” by Lee’s description—he surrendered it outright. Other Confederate generals followed suit, especially because the generous terms being offered by Union commanders made the decision to surrender more palatable. Echoing Lincoln’s second inaugural address, which promised “malice toward none,” General Grant effectively pardoned Lee’s entire army, offered parole so that his soldiers could return home rather than be imprisoned, allowed his officers to keep their side arms and horses, and even fed his starving men.

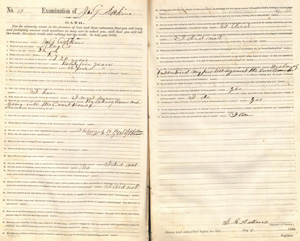

Recognizing the inevitable end of their rebellion, the Confederate cabinet dissolved itself on May 5, 1865, leaving the Confederacy without a government. Davis and his wife sought refuge in a foreign nation and were on their way to book passage overseas when they were captured by Union soldiers at Irwinville, Georgia, on May 10. Davis was indicted for treason and kept a prisoner for two years at Fort Monroe, Virginia, but he was released on parole in May 1867. He never faced trial because it would impede reconciliation for the nation and because a trial would spark debate about whether state secession had been legal all along. On December 25, 1868, President Andrew Johnson pardoned all members of the rebellion, but the 14th Amendment to the Constitution denied Davis and other high-ranking Confederate officeholders the right to hold public office in the future.

With the end of the Confederate rebellion apparent to everyone, the month of May 1865 ended with a Grand Review of the Armies in Washington, D.C., and the dismantling of a large portion of the Union war machine. The Army of the Potomac, with 80,000 soldiers, marched through the federal capital on May 23, and the 65,000-man Army of Tennessee, commanded by William T. Sherman, marched the following day. One week later, both armies disbanded and the nation looked toward Reconstruction.

Rebuilding in Missouri and Kansas

As Unionists reveled at the end of the war, the residents of Missouri and Kansas had to consider how to reconcile their differences, rebuild, and move forward. The correspondence between a Missouri couple who were engaged to be married hinted at the various challenges faced in recovering from a decade of violence along the Missouri-Kansas border that predated the Civil War itself.

The surviving letters between John A. Bushnell, a resident of Clinton, Missouri, and his fiancé, Eugenia Bronaugh, of Hickory Grove, Missouri, depict the immediate postwar situation in May 1865. Bushnell, a merchant and former slaveholder who nonetheless supported the Union cause, seemed optimistic about an improving economy and wrote to Bronaugh:

Sedalia is improving very rapidly and property of every kind is advancing rapidly. The prospects of peace seem to be the moving power and motion for action, dollars that have been laying dormant for several years are being brought to light and used. This is a good feature and I do hope our good Henry County folks will follow the example and use money and labor too for the benefit of the country and cease using their tongues and harsh threats there by stirring up discord and creating destruct instead of cultivating peace and harmony by a more sensible course.

For her part, though, Eugenia Bronaugh depicted a war-torn and dangerous landscape in Hickory Grove, where she lived with her family in the eastern part of the state. She mentioned that it was still not safe for Bushnell, a known Unionist, to risk traveling to see her. The pair had already been separated for most of the war due to the number of secessionist guerrillas in the area of Hickory Grove. She wrote that she heard news of “two precious relatives” but regretted that she did not have the “opportunity to advise them not to visit Mo. I fear they may do so. I fear they cant believe dangers are so thick & may not change for the better.”

Bronaugh also wrote about a different set of relatives from Saline County in the central part of the state along the Missouri River:

They were all low spirited & anxious to leave for another clime; to leave their country, where there was so much to remind them of evils committed in the name of “Liberty" Oh would it not be pleasant for us all to “Swap about" go where strange faces & new scenes await us, where there would not be so much to remind us of the cruelties of war, our troubles. I think so, & we would so gladly leave.

Bronaugh’s letter made it clear that the state had considerable work to do to quell the animosities that had accumulated since the start of border violence relating to “Bleeding Kansas” after the mid-1850s.

Another challenging but easily overlooked aspect of recovery for Missouri was that it needed to rebuild its state government. The government in place at the outset of the war had broken apart when Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson and a number of legislators took control of the Missouri State Guard and declared their intentions to secede, even though a special convention called to consider the question of secession had formally rejected the proposal. A provisional government backed by the Union military governed the state for the duration of the war.

In May 1865, Missouri’s provisional government was still in place, but in the following month the state adopted the so-called “Drake Constitution,” named for Charles D. Drake, a Radical Republican and the principal author of the document. The new document enshrined emancipation of the state’s slaves (which had occurred in January), established a formal government to replace the provisional Union government, and required Missouri’s male citizens to take an “Iron-Clad Test Oath” to prove their loyalty to the Union before they could vote in elections. The loyalty oaths in particular caused outrage among conservative opponents who referred to it as the “Draconian Constitution.” Far from the intentions of its drafters, the punitive nature of the new constitution provided a convenient rationalization for guerillas who continued their banditry in the months and years after Appomattox.

Missouri Bushwhackers Continue Fighting

Even as most Missourians sought to move on from the war, a number of hardened guerrilla fighters, or "bushwhackers," as they were known, had grown accustomed to personal feuds, brutality, and spoils of plunder. This atmosphere of violence is illustrated in the diary of C.T. Kimmel, an assistant surgeon in the 2nd Missouri State Militia Cavalry.

Recorded on May 10, 1865, Kimmel’s first diary entry noted that he was mustered out of service. He seems to have boarded a west-bound steamboat on the Missouri River and the Grand River before arriving at Brunswick, a town in the central part of the state along modern-day State Highway 24. He arrived in Brunswick on the 14th and found “a room” to use for an office the following day. Fortunately he deposited his money and bonds in a bank that day, because on the 16th someone broke into his office and stole some items.

On May 21, Kimmel’s diary hinted at more lawlessness with his reference to Jim Jackson, a notorious bushwhacker who, according to Kimmel, was still riding with 10 other guerrillas. Kimmel recorded that “Captain Dolman” left to pursue Jackson with a company of men. The next month, Jackson attempted to leave the state for Illinois but was killed by Union militia in Pike County.

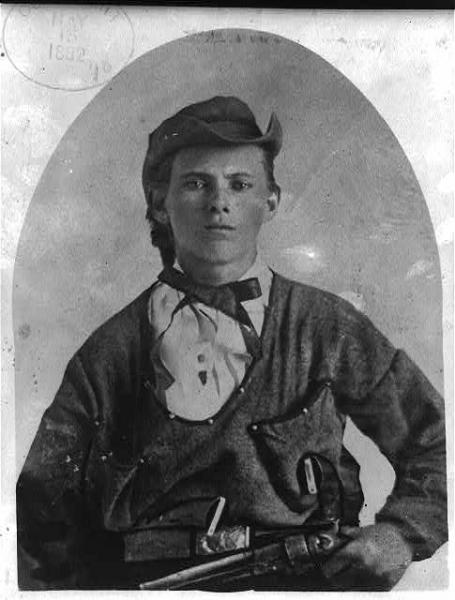

Kimmel’s May 24 diary entry mentioned a report from Lexington, Missouri, where a group of bushwhackers under command of Archie Clement had approached the town and demanded its surrender on May 11. The rebels failed to take the town but continued looting the area. Kimmel’s diary entry records that “guerrillas were surrendering at Lexington,” but at least two of them escaped to continue fighting: Clement and Jesse James, who was then just 17 years old. Demonstrating how long it would take for the strife in Missouri to end, Clement returned to Lexington a year and a half later, on election day, November 6, 1866, and successfully occupied the town. Clement capitalized on widespread animosities toward Missouri’s Radical Republicans, and Democrats carried the local election. Finally, Governor Thomas Fletcher ordered the state militia to restore order, and the militiamen killed Clement in a running gunfight as they retook the town.

Two more entries in Kimmel’s diary attest to the continuing violence in Missouri. On May 25, a short entry recorded, “Dollman returned from Carroll Co. Killed no Rebs.” Likewise, on May 31, Kimmel recorded that guerrillas approached Brunswick and he “accompanied a squad of soldiers in pursuit of them.” He returned to town that day, but “the troops went on in pursuit.” Kimmel made several additional references to guerrillas in June, and in general his account differed little from wartime diaries from the area, as if the war had never ended in his part of Missouri.

With such a pronounced bushwhacker presence, Union soldiers in Missouri had to remain on a wartime footing even as tens of thousands of federal soldiers were already being mustered out of service at the end of the war. The office of the provost martial in St. Louis received instructions that wartime discipline should still be maintained and that deserters should be “arrested and disposed of in the same manner as prior to the date of the proclamation of the President except that until further orders no rewards will be paid for their apprehension."

Learn more about the violence of the postwar period and the legacy of the Civil War in Missouri and Kansas from an essay by Pulitzer Prize-winning author T.J. Stiles.

Among the rebels who continued fighting was William Clarke Quantrill, whose August 1863 raid on Lawrence, Kansas, had cemented his reputation as perhaps the most notorious of all of the bushwhackers. Following the raid, Quantrill’s Raiders wintered in Texas, where they split into two factions due to a dispute over the distribution of their spoils. Their lawlessness resulted in a warrant being issued for Quantrill’s arrest, and he returned to Missouri as a refugee from both the Union and Confederacy with few or no followers. Later in 1864 or early 1865, Quantrill and a few others entered Kentucky, presumably because Union forces were gaining control of Missouri and Kentucky had a reputation for lawlessness that would allow his bushwhackers freer reign. Quantrill’s relocation to Kentucky did not secure his safety, though, as he was less familiar with the terrain than he had been on the Missouri-Kansas border. On May 10, 1865, he finally fell into a Union ambush near Taylorsville, Kentucky, and was shot in the chest. On June 6 he died from his wounds at a Louisville military prison hospital.

Even with the most notorious bushwhackers dead and the Civil War officially over, years would pass before the longstanding animosities on the Missouri-Kansas border finally eased. Former slaveholders lamented the loss of their human property and resented what they saw as harsh measures taken against them by Radical Republicans. Former slaves often encountered dangers in such a hostile environment, and many chose to leave the state of Missouri and sought refuge in Kansas or other states. A few of the surviving bushwhackers, most famously including brothers Jesse and Frank James, turned toward train and bank robbery. Well into the next century, future generations of Missouri and Kansas residents would debate the meaning of their families’ experiences and of the legacy of the Civil War on the Western Border.