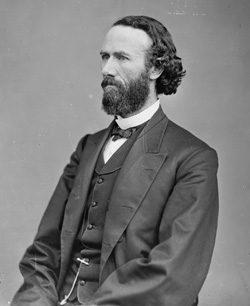

Mayor Robert T. Van Horn. Courtesy of the Missouri Valley Special Collections.

By Jason Roe, Kansas City Public Library

Each month in 2014, the Library will commemorate the sesquicentennial of the Civil War in Missouri and Kansas with a post derived from the thousands of primary sources that are digitized and incorporated into this website. The Library and its project partners collaborated to assemble this rich repository from the collections of 25 area archives, combining it with interpretive tools and original scholarship produced by nationally recognized historians.

Kansas City’s Mayor Mustered out of Service

In March 1864, Colonel Robert Thompson Van Horn, who was simultaneously the mayor of Kansas City, had been mustered out of service due to a reorganization of the Union Army’s Department of Missouri at the beginning of the year. Senator and Brigadier General John Brooks Henderson wrote to Van Horn on March 3 to express his dismay at Van Horn’s dismissal, but stating that he would continue to work to restore Van Horn’s appointment.

Van Horn, an Ohioan, came to Kansas City in 1855 and purchased the Kansas City Enterprise newspaper, renaming it The Western Journal of Commerce in 1857 and The Kansas City Daily Western Journal of Commerce in 1858. (Most historic accounts refer to the paper as The Kansas City Journal, but that name is something of a misnomer as it was adopted only after Van Horn sold the paper in 1896.)

Prior to the war, Van Horn’s paper espoused the existing circumstances on slavery: that Missouri should remain a slave state and that the Union should remain intact with a careful balance of Northern and Southern states. Van Horn’s political views focused almost exclusively on economic issues and the development of Kansas City in particular, both of which would be threatened in the event of war. In 1860, Van Horn won election for the mayor of Kansas City on the Democratic ticket, but after the Civil War commenced he switched to the Republican Party and received a commission as a major with authority to raise a defensive militia battalion in Kansas City, known as the “Home Guard.” He received considerable credit for consolidating Union control of the city in the first few months of the war, and in September 1861 he was wounded, captured, and soon released at the First Battle of Lexington.

See the document—signed by Gen. Sterling Price—authorizing the release of Maj. Robert T. Van Horn after his capture at the Battle of Lexington.Early in 1864, now-Colonel Van Horn was mustered out of Union service after his regiment was consolidated with another, leaving him without a command. Senator Henderson’s letter in March seems to indicate that the two parties were working to secure Mayor Van Horn’s appointment as a brigadier general, but Henderson noted that the number of brigadier generals remained “fixed” by national law and all available positions were filled by President Lincoln.

Henderson also hinted at Van Horn’s political ambitions. Van Horn secured a position as delegate to the National Union Convention in June, which would in effect decide the Republican nominee for the presidency. (In 1864 the National Union Party temporarily formed as a rebranding of the Republican Party in an attempt to draw moderate votes in the general election, while the “Radical Republicans” held a rival convention that nominated John C. Frémont, who ended up dropping out of the race prior to the general election.)

At the National Union Convention, Henderson speculated that President Lincoln would “favor immediate emancipation” and secure the nomination. He also speculated that the war could not last beyond 1864 and that after its end, disenfranchisement or other recriminations against former Confederates would not be necessary. “Rebellious sentiment will go with slavery,” Henderson wrote. Van Horn would ultimately serve as a delegate to the convention and end up winning his own election to the U.S. House of Representatives in the fall of 1864.

Read more about Robert T. Van Horn and Kansas City during the Civil War.As to the outcome of the upcoming election, Henderson was not sure of Lincoln’s success and cautioned, “Success politically, depends entirely upon military success this summer and we are starting out badly.” Indeed, by the late summer of 1864, enough doubt remained on both sides to lead Confederate Major General Sterling Price to organize a massive cavalry raid that he hoped would capture the state of Missouri for the Confederacy and cast a pall on Lincoln’s reelection bid. That raid would entangle Robert T. Van Horn and much of the rest of the state, but in March 1864 Van Horn still awaited word from General William S. Rosecrans, the commander of the Department of Missouri, about his return to formal involvement in the war.

Baptist Ministers React to General Orders, No. 61

The influence of General Rosecrans extended beyond strictly military matters. Like his predecessor in command of the Department of Missouri, General Thomas Ewing Jr., Rosecrans became embroiled in a controversy surrounding military infringement on constitutional rights. In response to continuing guerrilla violence, and especially due to a devastating raid on the civilian population of Lawrence, Kansas, Ewing had issued General Order No. 11 the previous fall, evicting thousands of residents from four border counties to remove the guerrilla’s base of support. For his part, Rosecrans fell from grace in the Union Army after a humiliating defeat at the Battle of Chickamauga in September 1863, and he replaced the embroiled Ewing at Kansas City in January 1864.

While Rosecrans would never issue orders as infamous as Ewing’s, pro-Southern Missourians complained that his General Orders, No. 61, issued on March 7, 1864, intruded on religious liberty. An 1870 book, Martyrdom in Missouri, went so far as to proclaim it, “Perhaps the boldest and most direct effort to strike down religious liberty and subordinate divine to human authority by military power during the whole war.” The orders issued by Rosecrans contained the following lines in reference to all forms of religious assemblies:

The interests of the country at the present time require that no such assemblages of persons, whose proceedings would be disloyal, and tend to foment discord and encourage rebellion, should be permitted. It is right and proper, therefore, that all members of such assemblages should give satisfactory evidence to the public of their loyalty to the Government of the United States, that their patriotism may be known, and that they be distinguished from those who seek its overthrow.

In effect, the order required Missouri’s ministers to swear loyalty to the federal government and maintain a pro-Union stance. A letter written from Reverend Joseph A. Lewis to Jonathan B. Fuller on March 13 further reveals the religious divisions between North and South and within the Baptist Church particularly. Years before the Civil War began, the nation’s largest denominations—Methodist and Baptist—divided on the issue of slavery between Northern congregations (which trended toward abolitionism and support of the Underground Railroad) and Southern ones (which tended to support the planter elite and find biblical justifications for slavery). In 1845, the Southern Methodist churches broke off from the Methodist Episcopal Church and called themselves the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. The church would not be reunited until 1939.

Read an essay by Dr. Christopher Phillips about Union loyalty oaths in the state of Missouri.The Southern Baptist Convention, forged across nine Southern states, similarly adopted a proslavery stance in 1845. For leaders in the Baptist Church in border states such as Missouri, the biggest concern rested in the political division within their own congregations. Reverend Lewis, of Glasgow, Missouri, questioned Reverend Fuller, of Louisiana, Missouri, about whether Rosecrans’s orders applied to the election of a pastor then under consideration. In this instance, Lewis was actually in favor of the orders: “If it does not [apply], can’t you help make it do so?” He continued to explain that he had “been thinking who I could get to oppose the proceedings; when the Gen. cut the Gordian Knot—and how shall I ever repay him?”

There is no surviving reply from Fuller, but in his numerous other letters and a diary, he revealed that his own pro-Union leanings were tempered with caution about political divisions in his own congregation. In a separate letter to his father written later in the year (this time in reference to President Lincoln’s proclamation of a National Fast Day), Fuller wrote, “I am afraid that my congregation may split upon that rock. I fear that even the utmost mildness and christian charity of my utterance will not save me, from offending some one's sensitiveness. But I suppose there is nothing for it but to speak out and take the risks.”

Although the letter of March 13, 1864, was little more than one initial reaction to a Union general’s orders, it speaks to the intense cultural, political, and religious divisions that could be felt even within the walls of one church.

Confederate Prisoner of War

Equally intense pressures fell on a pro-Confederate married couple from Savannah, Missouri, located 17 miles north of St. Joseph. Mary E. Bedford wrote to her husband, Lieutenant Alex M. Bedford on March 8, 1864, saying that she just arrived back in St. Joseph from visiting family in Kentucky, and that she would travel home the following day. She continued to remark on the break from violence that the winter had brought, writing, and “I hope it will continue so.”

If the March letter is read alone, it appears to have been part of a normal exchange for a couple separated by the war, but the nature of their separation was unique. The earliest surviving correspondence between the couple dates from November 1862, when Alex wrote to his wife to say that he had been wounded and taken prisoner in a battle near Corinth, Mississippi. He described his wound, writing, “the ball entered my left side & come out near my back bone.” He continued to say that a doctor believed the ball carried some of his shirt into the wound, and “until that decays it will hurt me more or less.”

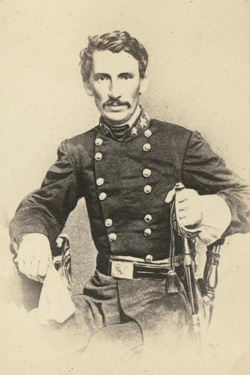

Alex Bedford evidently secured a release and managed to recover from his wounds. In 1863, he was serving under command of Brigadier General M. Jeff Thompson, of the secessionist Missouri State Guard. Thompson led Confederate cavalry in southeast Missouri in 1861, where he earned the cognomen, “Swamp Fox of the Confederacy.” He then led a riverine fleet in 1862, and fought in Arkansas in 1863. In August 1863, Thompson and a portion of his command were captured in Arkansas and later imprisoned in the Gratiot Street prison in St. Louis, then Johnson’s Island near Sandusky, Ohio, and finally at Fort Delaware on an island in the state of Delaware. Later in 1864, Thompson was exchanged and released, and went on to join Major General Sterling Price on his epic cavalry raid into Missouri.

Read the full correspondence between Alex and Mary Bedford.Alex Bedford suffered a slightly different fate. His letter to his wife on October 31, 1863, reveals that he was imprisoned with Thompson on Johnson’s Island. Later letters confirm that Thompson was also transferred to Fort Delaware, but unlike M. Jeff Thompson, he would remain imprisoned until the end of the war while suffering from a fluctuating state of health. Given all they had gone through, by the time Mary Bedford wrote to Alex Bedford in March 1864, her words must have been sincere: “I hope & trust the time will soon come when you can return home to enjoy the comforts & blessings of home.”