Missouri artist and Union officer George Caleb Bingham immortalized Order No. 11 in his painting, Martial Law (or Order No. 11). Wikimedia Commons image.

By Jason Roe, Kansas City Public Library

Each month in 2014, the Library will commemorate the sesquicentennial of the Civil War in Missouri and Kansas with a post derived from the thousands of primary sources that are digitized and incorporated into this website. The Library and its project partners collaborated to assemble this rich repository from the collections of 25 area archives, combining it with interpretive tools and original scholarship produced by nationally recognized historians.

Reflecting on the Guerrilla Violence of 1863

One hundred fifty years ago, Kansans and Missourians warily greeted the fourth year of the secession crisis and Civil War. In the previous year the Union Army had gained an upper hand in capturing Vicksburg, Mississippi, repulsing General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, and gaining the upper hand in the Chattanooga Campaign in Tennessee. Balancing those advances for the Union were the unprecedented casualties suffered, as well as setbacks in Northern morale that manifested in the New York City draft riots and the ascendance of the Northern Peace Democrats, known as “Copperheads,” who opposed Lincoln and wanted to make peace with the South rather than continue the war and reunite the nation by force.

Along the border shared by Missouri and Kansas, the fall of 1863 had brought a culmination of the guerrilla warfare conducted by pro-Union “jayhawkers” from the Kansas side and pro-Southern “bushwhackers” from Missouri. The infamous bushwhacker William Clarke Quantrill raided Lawrence, Kansas, on August 21 and killed between 160 and 190 men and teenaged boys. In response, and to undermine civilian support for Quantrill’s Raiders and other Missouri bushwhackers, the commander of the District of the Border, General Thomas Ewing Jr., issued the infamous General Order No. 11, which forcibly removed the non-urban populations of four counties in western Missouri, including Jackson, Cass, Bates, and northern Vernon Counties.

Even as Ewing’s men forced thousands of civilian residents to evacuate their homes, Confederate Colonel Joseph O. Shelby led 800 cavalry from Arkansas into central Missouri on one of the epic cavalry raids of the war. While the Union forces ultimately repulsed Shelby’s attack, it had the effect of raising pro-Southern Missourians’ morale in the wake of General Ewing’s Order No. 11. The raid also served as a precedent for an even greater raid that would occur in the fall of 1864, but as of January 1864, border residents were still preoccupied with the ongoing guerrilla violence and predictions of another large-scale Confederate cavalry raid were still several months away.

Divided Missouri: Union or Confederate?

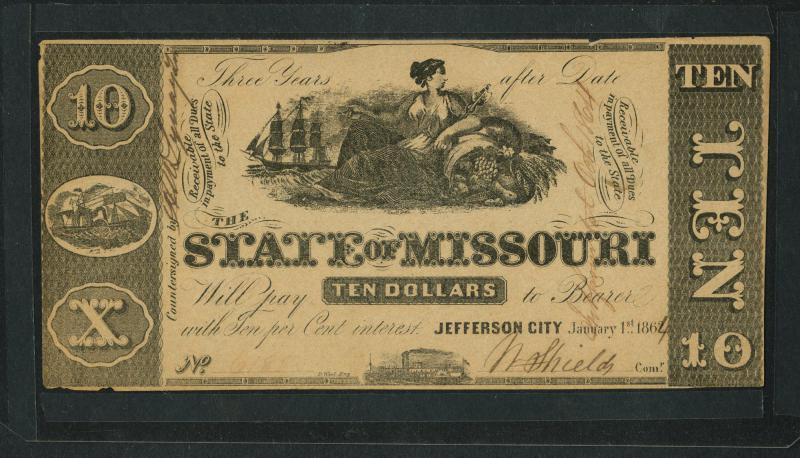

A sign of the enduring political divisions in Missouri on January 1, 1864 can be seen in this $10 Missouri Note, which was a Confederate promissory note, issued from the capital city of a Union state! How did this happen? In the early summer of 1861, Missouri’s elected governor, Claiborne Fox Jackson, had fled from the capital of Jefferson City with a number of supporters and elements of the secessionist Missouri State Guard. They fled to the southwest part of the state before winning the Battles of Wilson’s Creek, Dry Wood Creek, and Lexington, before retreating southward for the winter. On November 2, 1861, the Missouri General Assembly, consisting of Jackson and other deposed members of the Missouri state government, voted at Neosho, Missouri, to secede from the Union. On November 28, 1861, the Confederate States of America officially admitted Missouri, and many battle flags of the 11-state Confederacy displayed 13 stars to include Missouri and another Union-controlled border state, Kentucky. Meanwhile, the Union set up a provisional military government that would ostensibly control the state of Missouri throughout the war.

Confederate currency was issued by the central government and by individual state governments, and in this case, the deposed government of the state of Missouri promised to reimburse the bearer of the $10 with interest in three years. Looking carefully at the note, we can see that the original printed issue date of January 1st, 1862 was overwritten by hand to read 1864. The book Confederate States Paper Money, by Arlie R. Slabaugh, explains that although the notes were printed in 1862, many were not distributed until 1863 or 1864. Technically, this was a promissory note only, one which could be redeemed for Confederate currency after the rebellion succeeded. Of course, all Confederate paper money declined in value throughout the war, and a note backed by the deposed government of a state under Union military control in 1864—even as the Confederacy’s prospects for survival worsened—could not have been worth anything except to the most fervent believers in a Southern victory. Today, the notes can range in value from $50 to $250, depending on condition.

Dilemmas over Emancipation in Missouri

Read Professor Diane Mutti Burke’s essay about the collapse of Missouri’s slave system during the Civil War.More tangible property issues can be seen in the ways that some Missourians handled their human property, slaves. As of January 1864, Missouri’s slaves were not yet freed, with the exception of those who satisfactorily served in the military (President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation only applied to the areas not yet under Union control). Nevertheless, with the president proclaiming the destruction of slavery a goal for the war, and with Union prospects improving after Chattanooga and Gettysburg, the future of slavery in the Northern border states was uncertain at best. Missouri slaveholders had to decide among attempting to sell their slaves, trying to request compensation for their slaves serving the Union Army in exchange for freedom, freeing their slaves outright, or waiting until the end of the war and the presumed end of slavery in hopes that the federal or state government would compensate them for their property losses.

From January 1864, the library’s website contains two documents that reflect such decisions. This one is a deed of emancipation, created on September 4, 1863 and signed by two witnesses, declaring that James O. Swinney will emancipate his slaves on January 1, 1864. Swinney explained his reasoning as being “in view of the present condition of the institution of slavery.”

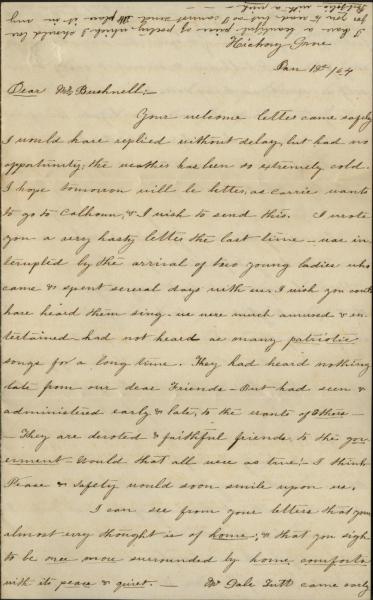

Another document from January 12, 1864, demonstrates the complicated and intensely personal nature of decisions to free slaves . Besides seeing slaves as property, some slaveholders held a strong affinity for their slaves, who, after all, may have been owned by one family for their entire lives. One case appears in the correspondence between a western Missouri merchant, John A. Bushnell, and his longtime fiancé, Eugenia Bronaugh. Bushnell lived in the western part of the state in Calhoun, Henry County, Missouri, although his mercantile business required frequent travel. Meanwhile, Bronaugh lived in Hickory Grove, Missouri, about 55 miles west of St. Louis.

The reasons for Bushnell and Bronaugh’s protracted separation and engagement become evident when the series of correspondence leading up to 1864 is examined. A letter from Bushnell on July 16, 1863, describes his efforts to apply for an exemption from Missouri’s new draft, by selling his belongings to pay his way out of service. This and other letters show that he struggled with finances as the guerrilla violence disrupted the economy. But Bushnell did not sell his human property, and in fact he freed his slaves by the end of 1863. Far from cutting them loose, his correspondence from December of that year reveals that he felt an obligation to ensure the wellbeing of his former slaves by renting a house for them at personal expense, and “let them work and see what freedom is, just to try it.” Bushnell’s letter reveals that he was considering hiring some of his former slaves and effectively turning them into servants rather than slaves, which demonstrates how complex the economic and social transition to freedom could be for people who had legally been property their entire lives.

Bronaugh’s letter to Bushnell on January 12, 1864 reveals his motivations for releasing his slaves; both of them were devoted to the preservation of the Union. Bronaugh described entertaining pro-government friends and singing patriotic songs, while virtually all of Bushnell’s letters referenced that he wished he could visit her in Hickory Grove or that she could travel, but that he was afraid of doing so because of the bands of pro-Confederate bushwhackers in the area.

The separation of Bushnell and Bronaugh, and consequently their engagement and surviving correspondence, would continue through 1864 and indeed until the end of the war. Their troubles, like those of Missourians and Kansans generally, were poised to continue and even escalate as the war continued into the new year.