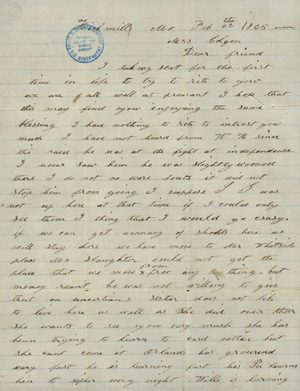

Samuel J. Reader's painting of Price's Raid during Reader's POW capture, completed in February 1865. Image courtesy of the Kansas Historical Society.

By Jason Roe, Kansas City Public Library

In the spring of 2015, the Library commemorates the sesquicentennial of the final months of the Civil War in Missouri and Kansas with a post derived from the thousands of primary sources that are digitized and incorporated into this website. The Library and its project partners collaborated to assemble this rich repository from the collections of 25 area archives, combining it with interpretive tools and original scholarship produced by nationally recognized historians. Sign up to receive this newsletter via email »

Kansas Farmer Paints the War

In February 1865, still in the depths of winter, residents of Missouri and Kansas found plenty of time to reflect on their losses in the war, on the battles or other struggles they experienced, and on the possibility that the war might continue for another year. Among the notable chroniclers of the war in those two states was a farmer and amateur artist named Samuel J. Reader, who moved from western Illinois to a farmstead at Indianola, near Topeka, Kansas, in 1855. As a resident of territorial Kansas, he witnessed parts of the "Bleeding Kansas" conflict and the Civil War first-hand. He recorded his experiences as a Free-State and pro-Union partisan in a diary, in his autobiography, in sketches, and in paintings.

Reader vehemently opposed slavery and sided with the Free-State Party in Kansas, but he also opposed the use of violence in the style of John Brown. He nonetheless fought in one skirmish in the Bleeding Kansas era, believing his participation to be in defense of Free-State settlers against proslavery aggressors. In September 1856, proslavery partisans had recently burned a Free-State settlement at Grasshopper Falls and threatened to attack more Free-Staters. In response, James H. Lane, a former lieutenant governor and congressman from Indiana and soon to become known as a "jayhawker," raised the 2nd Kansas State Militia and sought out the proslavery force of some 40 men. Samuel Reader joined Lane as his militia converged on the proslavery men at Hickory Point, a settlement on the military road between Fort Riley and Fort Leavenworth.

In the Battle of Hickory Point, Reader joined the attacking Free-State forces that were driven back on September 13. On the following day, a second force from Lawrence renewed the attack but withdrew when a ceasefire was called. One proslavery man was killed and several others were injured on both sides, making it little more than a small skirmish, but it was one of the numerous episodes of violence that gave "Bleeding Kansas" its name and made Kansas Territory the center of a national debate over the expansion of slavery into Western territories. Helping elevate the profile of the incident was a painting by Samuel Reader, called Battle of Hickory Point.

Reader's second foray into warfare came eight years later, in the fall of 1864, as the Confederate Army of Missouri, under command of Major General Sterling Price, crossed the state of Missouri in a grand cavalry raid and left devastation in its wake. As Price's cavalry closed in on Kansas City, Missouri, the Union raised militia from Kansas to stop the Confederate advance. Reader joined a company from Topeka in the 2nd Kansas Infantry, incidentally commanded again by General James H. Lane. At the Battle of the Blue on October 22, 1864, the Union defenders retreated, and many, including Reader, were taken prisoner. However, Price's army suffered a crushing defeat the next day at the Battle of Westport and retreated south. Reader was still a prisoner on October 25 when Price lost two divisions at a crossing of Mine Creek.

Reader finally escaped as, in the chaos that ensued after Mine Creek, he was mistaken for a Confederate soldier and used the opportunity to flee. He could be mistaken as a Confederate because Price's men were desperate for clothing and boots, and one of the soldiers traded his tattered grey coat for Reader's Union blue coat. Shortly after his capture, Reader also had to pull the boots of his friend who had been killed and nearly had to give up his own boots to his captors. Tragically for the Southerners, when they were defeated at Mine Creek, hundreds were summarily executed because they wore captured blue coats like the one taken from Reader and were presumed to be spies or guerrillas.

The Kansas Historical Society currently holds the documents and paintings created by Samuel J. Reader. See the finding aid for his papers here, and read his three-volume autobiography online.After his harrowing experiences, which included a forced march and multiple death threats, Reader recorded the incidents in his diary, in paintings of the Battle of the Blue and the Battle of Mine Creek, and, years later, in his multi-volume autobiography. For someone with such a small amount of experience in battle, Reader wrote far more about his experiences than most soldiers, which added up to hundreds of pages of writing and sketches. Perhaps Samuel J. Reader's need to document and analyze his experiences can be summarized best in volume three of his autobiography, where he wrote, "Confidence increases as the battle goes on, until little more fear is felt than during a very violent thunderstorm. A battle is one of those things that seems more terrible in the contemplation, than in the actual participation." When he finished his painting, Battle of Mine Creek, on February 13, 1865, just four months after the battle, he was undoubtedly trying to grapple with the meaning of what he had been through. He continued his reflections until his death in 1914.

News from Hickman Mills, Missouri

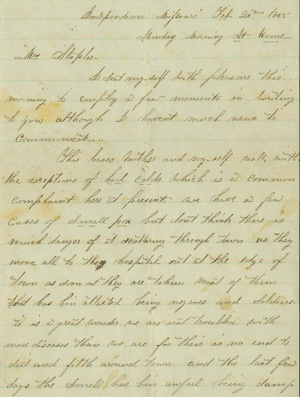

Like Samuel Reader, other residents of Kansas and Missouri were still coping with the aftershock of events that happened in the fall of 1864. Lizzie Deavenport, a resident of Hickman Mills, Missouri, found time in February 1865 to write a letter to a friend sharing news of recent events and mentioning more than 10 mutual acquaintances. Her letter, which Deavenport claimed was the first one she ever wrote to this friend, reveals the necessity of sharing news through letters in a region where travel could be restricted due to wartime circumstances.

The recipient of Deavenport's letter was a "Mrs. Colgan," probably Eliza Colgan, who was another resident of Hickman Mills and a relative through marriage of Harry S. Truman's family. Although located inside the boundaries of modern day Kansas City, Missouri, Hickman Mills was a relatively isolated community in the 1860s, located around 10 miles southeast of Kansas City. Locals at the time referred to it as Hickman's Mill, Hickman's Mills, or any one of a number of abbreviations. Residents of the community were exempted from General Order No. 11, which, as a Union response to Quantrill's Raid on Lawrence, depopulated the rural areas of Jackson, Cass, Bates, and northern Vernon counties. Despite the exemption, families like the Colgans—not to be confused with Truman's ancestors by blood who were Southern sympathizers and forcibly removed from Grandview, Missouri—still had to relocate due to threats of violence from one side or another, or due to economic hardships.

The identities of many of the people referenced in Lizzie Deavenport's letter are unknown, but she demonstrated personal connections to important events. She updated Mrs. Colgan about the aftermath of Price's Raid, writing that she had "not heard from" a mutual acquaintance named "W.H." She said that she learned he was wounded at the Second Battle of Independence, Missouri, but not so severely that it kept him from going on with his unit. Unfortunately the letter does not clarify which side W.H. fought in, but the battle occurred after Price's army pushed a Union force under command of Major General James G. Blunt back from its defensive position at the Little Blue River on October 21. Blunt set up defenses at Independence and the battle was fought on October 21 and 22. On the first day, Price's army captured the center of the town, but on the second day, Price was attacked from the northeast by a pursuing force of 10,000 Union cavalry under command of Major General Alfred Pleasonton. After the fighting at Independence, Price continued his advance toward Kansas City, but at Westport on October 23, the Union forces partially surrounded Price's army on the west, north, and east. The Second Battle of Independence would be remembered as one of several skirmishes that slowed Price's advance until the Union forces could join to defeat his army in the more decisive Battle of Westport.

The letter also contained references to other disruptions experienced by Deavenport, who seemingly had to move to a home owned by a Mr. Whitside due to wartime circumstances. She also wrote of several children who were growing, learning, acting mischievously, and otherwise trying to live normal childhoods despite the chaos taking place around them. Such hints of daily life are the hasty descriptions of families trying to live normal lives in trying times.

Toward the end of the letter, Deavenport provided a clear but discouraging description of the condition of Mrs. Colgan's home:

your home place does not look like it did when you was there. there is not but one hole window in your house[.] some of the trees are [broken] down[.] your house has been [mighty] abused[.] no boddy is wiling to live on your place[.]

Conditions in Independence, Missouri

More hints of the everyday lives of citizens living on the Western border can be seen in a letter from a resident of Independence, Missouri, named "S. Shelly," who wrote to someone named Mrs. Staples on February 20, 1865. The collection doesn't document who these people were, or even indicate whether Shelly was male or female, but the letter is a representative sample of civilian views of the war. What is striking about correspondence from this time is that, despite the availability of news indicating that the Confederacy was on its last legs by February 1865, few people could imagine that the war would finally end in the next few months.

The tone of Shelly's letter, similar to many from this time, is dour. It begins by mentioning that her and mother were ill, but fortunately with no more than colds. More critically, several cases of small pox had hit the town but officials believed the outbreak to be contained. Describing conditions in the town, the letter states, "it is a great wonder we are not troubled with more diseases than we are for there is no end to dirt and filth around town and the last few days the smell has bin awful...." The letter continues to predict that more militia forces will be raised in the upcoming week: "I dont suppose any one will be exempted unless they are blind in boath eyes or boath arms taken off."

Beyond those updates about the town of Independence, Shelly assured Staples that several friends were well, although she had not been able to communicate with a few of them owing to mail routes that had been disrupted by "Indian hostilities." While Shelly offered no hint of optimism that the war would end, the letter did include a note that "we have fared exceedingly well under the circumstances."

Even as Missouri and Kansas residents, who had experienced turmoil and intermittent guerrilla warfare since the passing of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, could see no end to their struggles, the war was well into its last phase by February 1865, just two months before Robert E. Lee's surrender at Appomattox. In the previous December, Major General William T. Sherman's "March to the Sea" resulted in the devastation of Confederate economic infrastructure and the capture of Savannah, Georgia. Concurrently, Major General Ulysses S. Grant's Siege of Petersburg stressed the Confederate defenses of the cities of Petersburg and Richmond, Virginia, between June 9, 1864, and April 1865. Even though the siege never fully cut off the enemy's supply lines, and as a result is not considered a true siege, it placed the Confederate capital city in peril for an extended period, bogging down Confederate armies that were badly needed across the South.

Opposing Grant, Lee's "Army of Northern Virginia" struggled to replenish its forces or even to feed and equip itself to oppose the Union attacks. Union forces extended their advances deeper into the South on multiple fronts as the Confederate supply lines evaporated, their railroads were destroyed or fell into disrepair, and their remaining armies lacked proper clothing, equipment, and sufficient rations. As Southern soldiers starved, their morale dwindled and it became increasingly difficult to mount a defense.

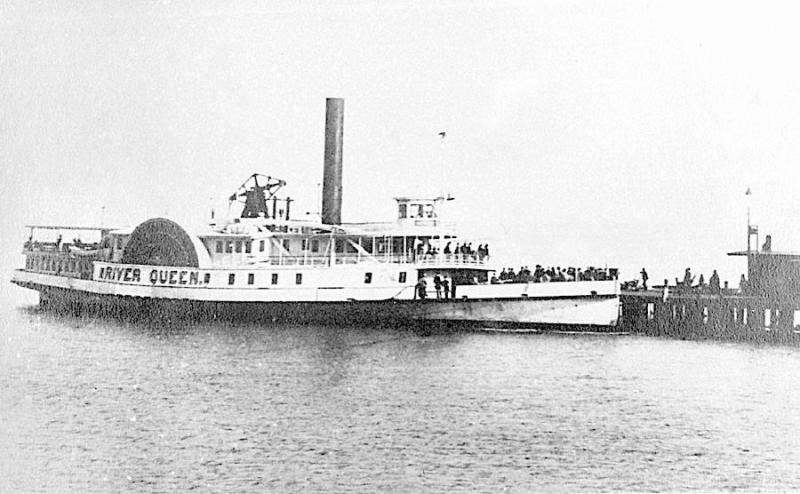

The clearest sign that the Confederacy was preparing to surrender emerged in February 1865 at the Hampton Roads Conference, which was held on the third of the month on a steamboat. President Lincoln and Secretary of State William H. Seward represented the Union, while the three representatives of the Confederate government included Vice President Alexander H. Stephens, Assistant Secretary of War John A. Campbell, and Senator Robert M. T. Hunter. There were no official records taken, and those present offered differing details about what was discussed. Following the conference, Lincoln did publicly propose an amnesty measure that would have offered up to $400 million in compensation to slaveholders in exchange for their surrender and the ratification of the 13th Amendment. Lincoln's proposal proved to be unworkable due to its unpopularity in the North. On the opposing side, Confederate President Jefferson Davis claimed that his delegates reported that Lincoln had demanded unconditional surrender. Little resolution came out of the conference, but the fact that the two sides were discussing the terms of Southern surrender signaled that the end of the American Civil War was finally approaching.