The 1st Kansas Colored Volunteers, a black regiment that mostly enlisted escaped slaves, fighting at the Battle of Island Mound, March 14, 1863.

By Jason Roe, Kansas City Public Library

Each month in 2014, the Library will commemorate the sesquicentennial of the Civil War in Missouri and Kansas with a post derived from the thousands of primary sources that are digitized and incorporated into this website. The Library and its project partners collaborated to assemble this rich repository from the collections of 25 area archives, combining it with interpretive tools and original scholarship produced by nationally recognized historians.

Contrabands and the Union Cause

As February 1864 dawned, the cold winter and the Civil War continued to exact misery on the residents of Missouri and Kansas. John A. Bushnell and Eugenia Bronaugh, fiancés separated by wartime circumstances (John in Calhoun, Missouri, and Eugenia in Hickory Grove, Missouri), continued their correspondence and contemplated taking the risk of visiting one another.

Bushnell, a pro-Union merchant, wrote to Bronaugh on February 11, 1864, to say that he would be visiting her in two or three days. Among his reasons for not traveling sooner was that he had been sick in recent days, but also that he had “not succeeded yet in getting a house for my contrabands yet.” Bushnell included an underline for emphasis on the word “contraband,” which was a loaded term in the context of the Civil War. He seems to have been referring to his former slaves, whom he had released a few months before, and despite setting his slaves free, he continued to feel responsibility for their welfare.

This sentence was the only mention of Bushnell’s freed slaves from February 1864, but the use of the term “contraband” is revealing. Contraband refers to illegally smuggled products, and in early to mid-19th century parlance, the term could apply to another form of property: fugitive slaves. The Union military began to use the terminology in official documents in late-1861 to describe confiscated goods and escaped slaves alike, and indeed the Union policy that emerged was to undermine the Confederate economy by employing escaped slaves as laborers and even setting up special camps to house and educate them. The term should not be conflated with a legal status of freedom, however, because the Union still considered contrabands, like other confiscated goods, to be property seized from supporters of the Confederacy.

Still, the status of being contraband offered a significant improvement over slavery, and many former slaves assumed it would eventually lead to full freedom. Starting in January 1863, many could gain their freedom by serving in all-black regiments, as did a St. Louis slave named Spotswood Rice in February 1864. In Kansas, it should be noted, some African Americans might even have joined the service as early as August 1862, when the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteers mustered into state service as the nation’s first black regiment before such units were federally approved. Finally, after the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1865, contrabands and all other slaves finally gained full legal recognition as free citizens.

Read other historical documents that reference contraband.Assuming that John Bushnell was indeed referring to the slaves that he had officially freed, they would not have been considered contraband because they did not escape from the Confederacy and were already legally freed. Yet his previous letters reveal his deep pro-Union convictions, and by emphasizing the label of contraband, it is possible that his motivations for continuing to pour his financial resources into his former slaves, particularly in the wake of the Emancipation Proclamation redefining the war as a struggle against slavery, included the belief that his actions would support the Union cause. The reference is too brief for definitive analysis, and Bushnell’s letter from January 1864 reveals that he also felt a personal responsibility toward his former slaves, but the choice of terminology remains a tantalizing clue to the ways in which his personal struggle mirrored that of the United States.

Compensation for a Slave’s Service

Unlike Bushnell’s slaves, many slaves in Union-controlled border states joined the military, and due to two acts of Congress, dated February 24, 1864 and July 28, 1866, loyal slaveholders in border states could apply for compensation for lost services if their slaves joined the Union military, whether through enlistment or the draft. When slaves enlisted, their owners could take a loyalty oath and apply to receive up to $300. For owners of draftees, the amount dropped to $100.

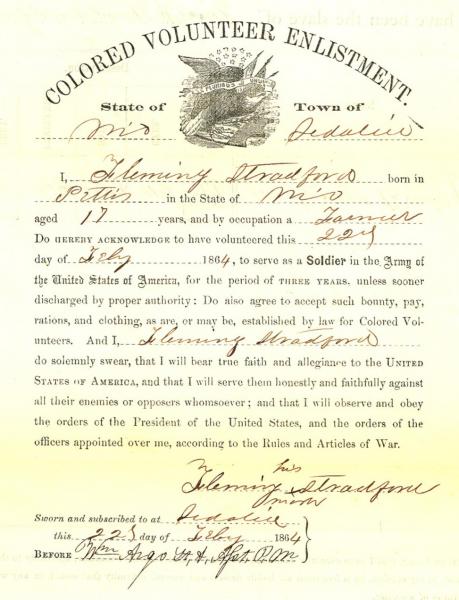

On February 22, two days prior to the act of Congress, a slave named Fleming Stradford, from Sedalia, Missouri, enlisted in the U.S. Army for a period of three years. When three years had nearly passed, on January 29, 1867, Stradford’s owner, E.M. Wooldridge, sought restitution for the service of his slave in this application for compensation.

Included in the second page of the application are Stradford’s original enlistment papers from February 1864, where his signature in the form of an “X” can still be seen between his first and last name. Positioned vertically over the X is a note that reads “his mark,” which unsurprisingly indicates that he was illiterate. Included in his enlistment forms is a medical certification that declares Stradford to be physically and mentally fit for duty. The form indicates that he was just 17 years of age.

For Wooldridge to receive compensation, he also had to include a claim form, which contained a signed and notarized Oath of Allegiance to the United States, as well as a statement that he had acquired Stradford through inheritance from his father, Powhatan Wooldridge, four years prior to Stradford’s enlistment. These forms were also signed by four witnesses.

Read this Guide to Civil War Slave Compensation Claims, from the St. Louis County LibraryUnfortunately for Wooldridge, a note on the seventh page of the packet reads “rejected,” without offering any further explanation. If the rejected status was accurate, it was possibly due to another act of the Reconstruction-era Congress on March 23, 1867, which invalidated new compensation claims for slaves’ military service to the Union. Still, although slavery in Missouri had officially ended with the ratification of the state’s “Drake Constitution” on June 6, 1865, Wooldridge’s documentation from 1867 indicates the continuing impact of slavery on former slaves, their masters, the economy, and American society.

In Missouri, the institution of slavery was in decline by February 1864, but its ultimate status would not be finalized until the war’s resolution after another year of fighting.

Kansas Governor Raises Militia

On August 21, 1863, the Missouri guerrilla William Clarke Quantrill led some 400 men in a devastating raid on the Free-State bastion of Lawrence, Kansas, and killed between 160 and 190 men and boys. By February of the following year, pro-Union residents of both states still feared the notorious Quantrill’s Raiders and were prepared to continue to escalate their efforts to undermine guerrilla efforts. The most infamous of these measures had been General Thomas Ewing Jr.’s issuance of General Order No. 11, which forcibly removed the non-urban populations of four counties in western Missouri, including Jackson, Cass, Bates, and northern Vernon Counties.

Other less-controversial measures continued into 1864. The governor of Kansas, Thomas Carney, wrote a letter to Major General James McDowell on February 9, 1864, informing him that he would “assume command of the militia of this city and vicinity, and superintend whatever arrangements may be made for the protection of this locality against attacks from guerrillas.”

On the surface the brief letter appears to be straightforward enough, but it reveals a window into Carney’s deep commitment to protecting the new state of Kansas from devastation during the Civil War. From any other politician, the closing line of the letter, “Any assistance that may be needed from me shall be promptly granted,” might have been met with suspicion. General McDowell, however, would have done well to listen to such a promise from Governor Carney.

In 1862, prior to assuming his role as governor in January 1863, the successful businessman Carney had loaned the state of Kansas a then-enormous sum of $25,000 to rescue it from severe budgetary strain. As governor early in 1863, it appears that Carney clandestinely paid $10,000 of his own money to raise a militia of 150 men to patrol the border against guerrilla violence. We can see evidence of this from an earlier letter to James McDowell, dated June 26, 1863, in which Carney disparaged Secretary of War Edwin Stanton’s decision not to approve a new regiment for the defense of Kansas. Carney wrote that he would “be compelled to foot the bill myself or abandon the helpless women & children to the brutal assaults of the ruffian raids that have so long cursed our state, which I shall not do. Protection I am bound to give & will do it. Come what will, God helping me.”

Read more correspondence from the embattled Kansas Governor Thomas Carney.What came to Lawrence, Kansas on August 21, 1863, was the most devastating guerrilla attack on civilians of the Civil War. But in the summer of that year, guerrilla activity had subsided to such an extent that the state militia had largely been disbanded by August, despite Carney’s efforts to maintain it. The regular military’s defenses proved to be inadequate against Quantrill’s surprise attack, but in the wake of Quantrill’s Raid, Carney’s General Order No. 1, establishing a new militia to protect Kansas, seems to have been more effective. Kansas did not suffer from such a devastating raid again.

Later in September and October of 1864, General James McDowell would be called upon to organize a defense of Kansas against a punishing cavalry raid that would bring a sizeable Confederate army to the very doorstep of Kansas at present-day Kansas City, Missouri, on October 23.

But in February 1864, any rumors of Major General Sterling Price organizing a huge cavalry force were still several months in the future, and the cold winter months offered a brief but welcome respite from large scale military action.