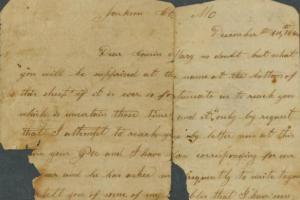

Mattie Jane Tate’s letter to her "Cousin Mary."

By Jason Roe, Kansas City Public Library

Each month in 2014, the Library will commemorate the sesquicentennial of the Civil War in Missouri and Kansas with a post derived from the thousands of primary sources that are digitized and incorporated into this website. The Library and its project partners collaborated to assemble this rich repository from the collections of 25 area archives, combining it with interpretive tools and original scholarship produced by nationally recognized historians.

Reflecting on 1864

As December 1864 began, the threat of cold weather brought many military campaigns to a halt and offered the possibility of less violence and bloodshed, but it undoubtedly caused the people of Missouri and Kansas to spend more time indoors, reflecting on their own experiences of the Civil War.

The year 1864 had begun in the shadow of Quantrill’s Raid on Lawrence and General Order No. 11, which largely depopulated the rural areas of four border counties known to be a refuge for Missouri’s pro-Southern guerrillas. Not merely a transitory event, the Union’s Order No. 11 displaced thousands of people who had the misfortune of living in Southern-sympathizing counties. Understandably, the people who lost their homes, property, or loved ones still resented the controversial order in December 1864.

On the 14th, a resident of Jackson County, named Mattie Jane Tate, wrote to her "Cousin Mary," to tell her "some of my troubles that I have seen and undergone within the last year." Tate’s letter made it clear that she had never written to her cousin before, but that she frequently corresponded with Mary’s father, who urged her to write to Mary. Tate explained that she had procrastinated but was finally writing and explained that she was the wife of Calvin Tate, who visited Mary and her father in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) when Mary "was quite small."

Mattie Jane Tate wrote of her husband:

alas I never shall hear his lovely voice again on Earth for he is gone gone from me forever and I am left with three small children to take care of .... Ewing made the Order No. 11 to devastate the Countys of Jackson--Cass[,] Bates and part of Vernon.

Her account went on to say that her family members "were all trying to get out" on a Sunday morning, as ordered, "But before they got off some Soldiers from Kansas came and taken My Father[,] Brother and my Husband and five others." The soldiers released Tate’s father and brother, but shot the rest "all to pieces" and left without burying them. According to Tate, none of the victims had fought for either side in the war, except for one of the men who had served in the militia in Kansas City for just two weeks.

Such accounts of Union brutality associated with Order No. 11 were common, although there is still no clear record of how many people were displaced or killed. For Mattie Jane Tate, the experience was as devastating as for the Unionist women at Lawrence who also lost their husbands, fathers, or sons to Quantrill’s Raiders in the fall of 1863. While the Lawrence women blamed Quantrill and his bloodthirsty followers for the retaliatory border violence, Tate placed the blame squarely on "Negro loving white men," adding that she wished blacks "were all in Africa." Furthering her bitterness, Tate’s father continued to support the Union side in the war, despite the loss of his son-in-law as a result of Order No. 11.

Recovery from Price’s Raid

Missourians and Kansans had plenty of other events to reflect on at the end of 1864. Foremost among them was Major General Sterling Price’s "Missouri Expedition," which culminated with the Battle of Westport in present-day Kansas City, Missouri, in October 1864. The raid left Price’s Army of Missouri in tatters before it split apart and retreated through Indian Territory on its way to Texas. Despite Price’s failure to achieve his objectives of capturing Missouri for the Confederacy and possibly ruining President Lincoln’s chances of reelection in November 1864, the raiders caused thousands of deaths and destroyed or plundered significant amounts of property. The Union civilians and soldiers who remained in Missouri and Kansas after the raid faced winter having to endure any losses they suffered.

One man, E.F. Slaughter, described the suffering left in the wake of Price’s Raid when he wrote to a woman named Eliza Colgan, from Hickman’s Mill in Jackson County, Missouri: "We have had large armies here of both sides and our corn[,] hay[,] cattle and vegetables disappeared quicker than we could raise them." Slaughter went on to say the he had "lost about 60 bushels of corn and some potatoes," but some of their neighbors had lost the entirety of their crop to the maneuvering armies that plundered any provisions they needed.

Still worse, the day before the Battle of Westport, E.F. Slaughter was captured (along with a unit of "home guards") by a division of Price’s army that was commanded by General Joseph O. Shelby. Shelby released the prisoners on parole the next morning, but they had to return home without any provisions or blankets. Slaughter and his fellow home guardsmen avoided a worse fate, though, as they heard "the roar of musketry and artillery [that] was without intermission for 4 or 5 long hours." Slaughter did not participate in the Battle of Westport, but he showed pride in the fact that rebel wounded were treated in Kansas City alongside the Union soldiers, demonstrating "that our armies are merciful as well as brave." He held reservations about the war effort, adding, "but the widow and the Orphan can not look with pleasure on such scenes[.] it brings no comfort to them."

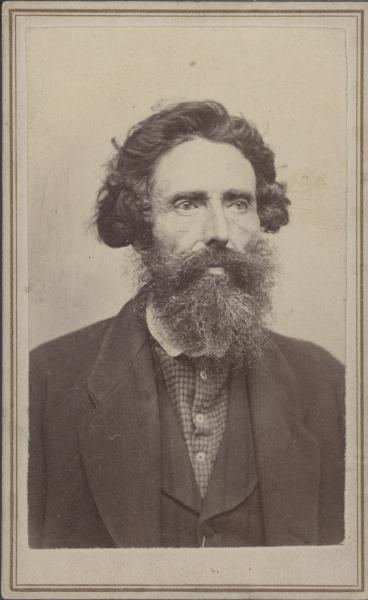

The emergency situation created by Price’s Raid brought others into the fold of the war. James Montgomery, a notorious Free-State jayhawker during the "Bleeding Kansas" conflict, rejoined the war effort after he had resigned his commission due to poor health. Montgomery’s letter to Major George L. Stearns, dated December 10, 1864, described his decision to fight against Price’s Raid just as he was recovering from his illness:

I had just got able to eat my breakfast at the table, when Price’s Raid brought everybody in Kansas, into the field. I took command of thirteen companies of white, and two of black militia, and joined Genl. Curtis, in Missouri, where we performed our share of service, particularly in the battle of Westport.

Montgomery’s own son fought in the Battle of Westport, and according to Montgomery, he "showed great steadiness of nerve, and skill as a marksman." Following their defeat at Westport, Price’s army retreated to the south along the Kansas side of the Missouri-Kansas border and soon suffered an even greater debacle at the Battle of Mine Creek as they crossed the muddy banks of the creek. It is uncertain whether Montgomery’s account refers to Mine Creek, but he was a resident of Mound City, Kansas, which was near the site of the battle, and he wrote, "a battle was fought close by it [Mound City], and in sight of my place." Montgomery explained that his wife, daughters, and other women from the town, "hurried to the field, in search of friends, each hoping for the best, but [fearing] the worst."

Following Price’s Raid, Montgomery returned to his retirement and farming, and he complained that while the weather was "the best of the season" during the raid, there was too much rain after he returned home. Prior to the raid, he had plowed about 70 acres of land that he could not use for sowing wheat, but he admitted that he could probably still plant oats and Hungarian grass. James Montgomery, who will always be best remembered as a fighter for the Free-State cause, ultimately found himself as absorbed in agriculture and domestic concerns as he was in the final stages of the war.

Guarded Hopes for 1865

As 1864 drew to a close, many of the surviving documents show that the citizens of Missouri and Kansas were planning to protect their own families’ interests, while some cautiously hoped that the Civil War would finally come to an end in the upcoming months. Although James Montgomery was concerned about missing a prime planting time during Price’s Raid, his farm was doing quite well in other respects. He stated that his corn crop for the season amounted to 100 acres, with a production of about 33 bushels per acre, which he estimated would sell for as much as $4,950 total. Describing the prices of various crops and livestock, he wrote, "At these prices, farming pays better than fighting."

Montgomery had other ideas for making money after his retirement from the service. He noted that he could pay to send some young, eager men to Massachusetts or another state that would pay larger enlistment bonuses than Kansas, and thereby "benefit myself as well as them." Accordingly, Montgomery asked George Stearns, "to inform me what bounty your state pays, on enlistment, and what aid to the families of enlisted men."

Even as Missourians anticipated the end of the war, the seeds of continued unrest were sown with emancipation in January 1865, compulsory loyalty oaths, and lingering bitterness that would endure through the rest of the 19th century. Read more in an essay by historian T.J. Stiles.Abishai Stowell, a Union soldier from Mount Gilead in Anderson County, Kansas, similarly looked out for his family’s wellbeing, but he especially anticipated the end of the war. He wrote to his sister from Fort Smith, Arkansas, on December 15, 1864, expressing concern for her health and also providing "a list of prices here so that if you want to buy things cheap you will know where to find them." The common items he listed prices for included bacon, coffee, flour, chickens, apples, tobacco, whiskey, and thread.

Stowell further expressed his hopes for an end to the war, writing, "well times are pretty hard here now but there’s a good time coming by & by! And though we have to put up with considerable hardship & privations now; I am glad to be able to bear my part." He only wanted to see peace come about if it resulted from the end of slavery and the reunification of the United States, and events in the East indicated his wishes would be fulfilled. On December 21, the city of Savannah, Georgia, surrendered to Major General William Tecumseh Sherman, ending Sherman’s "March to the Sea" that had destroyed military installations, factories, railroads, bridges, civilian property, and other infrastructure. Sherman’s "scorched earth" tactics targeted the South's economic infrastructure and coincided with Major General Ulysses S. Grant's Siege of Petersburg to pressure the Confederacy toward submission. Sherman wired President Lincoln a brief message, "I beg to present you as a Christmas gift the City of Savannah, with one hundred and fifty guns and plenty of ammunition, also about twenty-five thousand bales of cotton."

With Sherman’s March to the Sea complete and victory in sight for the North, Abishai Stowell best summarized the mood of Union supporters in December 1864, when he wrote:

still the good work goes on in other places & the day of restoration has already dawned & soon the sun of peace (not copperhead peace) will shine again on this once happy land of ours as in times of old (only slavery will be abolished & suffering beyond description will be ended).