A print depicting the surrender of General Robert E. Lee. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

By Jason Roe, Kansas City Public Library

In the spring of 2015, the Library commemorates the sesquicentennial of the final months of the Civil War in Missouri and Kansas with a post derived from the thousands of primary sources that are digitized and incorporated into this website. The Library and its project partners collaborated to assemble this rich repository from the collections of 25 area archives, combining it with interpretive tools and original scholarship produced by nationally recognized historians. Sign up to receive this newsletter via email »

Lee Surrenders: "Our Confederacy has Played Out"

News spread quickly of Major General Robert E. Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House between April 9 and 12, 1865, leaving everyone from generals to civilians with difficult decisions about what to do next. Even though Lee's Army of Northern Virginia represented a small fraction of the overall Confederate military, its commanders and common soldiers widely agreed that the surrender of their most celebrated general marked the end of the rebellion. Alex M. Bedford, a Missourian and Confederate prisoner of war held at Fort Delaware, Delaware, summarized his feelings in a letter to his brother on April 13, "I Suppose you have heard of the Surender of Genl Lee & his army[.] they have gone up & our confederacy has played out & I will return home if permited by taking the oath or any other way."

Lee's surrender marked the most widely recognized end date of the war because it coincided with a long decline in the Confederacy's prospects and the surrender of Petersburg and Richmond, Virginia, on April 3, 1865. Those cities had suffered from a partial siege and continual attacks by Major General Ulysses S. Grant since June 9, 1864, and with Richmond's surrender, Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his cabinet were forced to flee the capital city. In addition to being split into pieces along the Mississippi River and along the route of Major General William T. Sherman's march from Chattanooga to Atlanta and Savannah, the Confederate States of America lacked regular access to overseas trade due to a Union naval blockade. Without the ability to trade its primary crop—cotton—and with an enormous portion of its adult male population under arms, the Confederacy could hardly manage to feed and clothe its soldiers. The Confederacy reached such a state of desperation that its Congress passed General Orders No. 14 on March 23, 1865, which for the first time allowed for enlistment of slaves in the Confederate military. While the measure would have paid equal compensation to slaves as to white soldiers, an extremely small number of slaves enlisted under it because it came so late in the war and because it did not offer freedom to those who served. The opportunity to run away and join the Union forces to fight against slavery was far more attractive.

Following the surrender of Petersburg and Richmond, General Lee retreated westward with plans of joining other Confederate forces in North Carolina, but Grant blocked his path at the small community of Appomattox Court House, where Lee determined to break through a section of Grant's lines that he believed was made up only of cavalry. After pushing back the first line of the Union forces and reaching the first ridge, Lee's Second Corps discovered a much larger force awaiting them and withdrew. Outnumbered nearly four-to-one, Lee's only option was surrender, which took place in the parlor of a house owned by Wilmer McLean on April 9, followed by a formal ceremony disbanding the Army of Northern Virginia on April 12.

With Lee's surrender, only 28,000 Confederates laid down their arms, while 175,000 remained. Still, Lee was the Confederacy's most widely renowned military commander, and the rest of its forces lacked sufficient food, clothing, ammunition, and supplies to continue the fight. The next most prominent surrender came on April 26, 1865, when General Joseph E. Johnston surrendered the Army of Tennessee and all other forces under his command in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, totaling more than 89,000 soldiers. Through the rest of April, May, and June, one Confederate commander after another surrendered, and Northerners and Southerners widely agreed that the war was at an end.

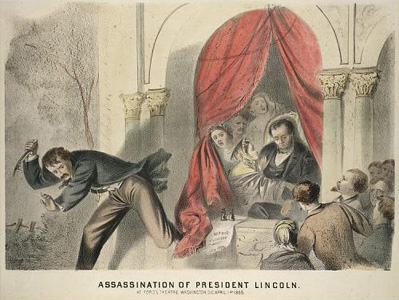

"Terrible News" of Lincoln's Assassination

Even with the war winding down, Northern officials could not rest with the looming challenge of reintegrating the Southern states and rebuilding the nation. President Abraham Lincoln expected to remain at the forefront of this difficult transition, but a mere two days after the disbandment of Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, Lincoln fell to an assassin's bullet and died the next morning on April 15, 1865. As news spread to Missouri and Kansas, reactions varied from ecstatic to apprehensive among Southern sympathizers and to a sense of devastation among Lincoln's supporters.

Rev. Jonathan Fuller, a Baptist minister and strong Union supporter from Kansas City, recorded his feelings in his diary while traveling by steamboat from Hannibal to Lagrange on the Mississippi River on April 15:

On Steamer "Warsaw" for Lagrange[.] At Hannibal heard the terrible news of Pres. Lincoln's assassination. All faces covered with gloom. Woe to the Rebels now. At Lagrange--all business was at once stopped--houses and flags draped and bells tolled.

On April 19, Fuller described holding a meeting at a church, "on occasion of the Presidents Funeral." Of the attendees who packed the church, he remarked that, "Four years ago not six of the throng would have gone ten steps to do the murdered statesman honor. Tempora mutantur." The Latin phrase translates to "times change," and Fuller's statement aptly described the shift in public opinion toward Abraham Lincoln, who in 1860 had relatively little experience and entered the Republican convention as a dark horse candidate for the party nomination. He managed to secure the nomination and was elected president of the United States, only to face a national crisis as one Southern state after another seceded before he could even be inaugurated into office. Reviled by the South as a radical abolitionist—even though that description did not ring true at the beginning of the war—Lincoln was far from universally adored in the North as it took four bloody years to suppress the rebellion. Even in the months leading up to his reelection in 1864, Lincoln feared that he would lose the election and that the federal government would seek a negotiated peace to recognize the Confederate States of America.

Only in recent months leading up to April 1865, since the surrender of Atlanta, Georgia, in September 1864, did it seem clear that the North was on its way to winning the war. By the time of Lee's surrender, Unionists could finally rally around Lincoln as a victorious commander-in-chief. Only days later, he was gone.

Contrary to the hopes of the conspirators who assassinated Lincoln and also attempted to assassinate Secretary of State William H. Seward and Vice President Andrew Johnson, the loss of the president did not throw the Union war effort into chaos or revitalize the Confederacy. Instead, the outcome was accurately predicted by one member of the 2nd Kansas Cavalry, who wrote in a letter to his sister on April 22:

the Union people feel the ... loss to be one that can never be repaid while the Secesh are overjoyed with the news but I hope that our grief and their joy will soon be diminished by the arrest and execution of the murders and a speedy restoration of the Union[.]

Indeed, John Wilkes Booth, Lincoln's killer, was shot by a Union soldier on April 26, and a military tribunal convicted four of the accused co-conspirators to death. On July 7, 1865, those four were executed by hanging. Controversially, the four convicted to die included Mary Surratt, the owner of the boarding house where Booth and his co-conspirators (including Surratt's son who escaped capture) plotted the assassination. Despite there being little more than circumstantial evidence to link her to the plot, she died alongside the other three conspirators on the gallows.

It is impossible to predict how Reconstruction would have proceeded or fared under President Lincoln's guidance, but his assassination immediately thrust Vice President Andrew Johnson, a War Democrat from Tennessee, into the presidency and left the Union without its wartime leader.

Laying Down Arms on the Western Border

Despite the tragic news of President Lincoln's assassination, the war continued to wind down, and orders to shutter a number of military operations spread almost immediately after General Lee's surrender. Colonel E.B. Alexander, a provost marshal in St. Louis, for example, received circular orders issued on April 18, April 21, and April 22, instructing provost marshals to cease drafting and recruiting operations, terminate rental and business agreements, discharge employees, including deputy provost marshals, and to return clothing and other equipage to the nearest post quartermaster.

As entire departments began to shut down, common soldiers on both sides of the conflict made preparations to return home. Abishai Stowell, a Union soldier in the 2nd Kansas Cavalry, planned to return home to Mount Gilead, Anderson County, Kansas. He had just learned of his father's sudden death and wrote to his sister that, "I could hardly realize that he was gone from us forever for when I left Kansas last August he was heartier than I ever saw before but we know not the day nor the hour when the son of man cometh."

Having been away from home for the last eight months, Stowell was unsure of his mother's financial state after the death of his father, but he wrote that he "sent a little money home a few days ago." Most of all, Stowell anticipated his return home, writing,

the prospect is good for me to go home in a few days for the war is just about ended: and I think that ours will be one of the first regiments that will be mustered out of the service: for the regiment is unfit for active service now (on account of having no horses), beside the mens time is out (or will be before they will have time to equip them).

Unionists like Stowell greeted the end of the war as an unequivocal blessing, but for Confederates it could be bittersweet or disillusioning. Alex M. Bedford, a Confederate soldier from Savannah, Missouri (located 17 miles north of St. Joseph), was captured in Arkansas in August 1863 and spent the duration of his captivity writing a series of letters to his wife and acquaintances at home. Bedford refused to take an oath of loyalty to the Union to secure a parole and return home despite longing to return home throughout the conflict, despite his family struggling to cope with his absence, and despite his poor health and failing eyesight. His correspondence made it clear that he believed the only honorable course of action was to wait for a prisoner exchange so that he could return to the Confederate cause.

After learning of Lee's surrender, Bedford began making arrangements to take a loyalty oath to the Union and secure a parole to return home. He first wrote to Joseph L. Bennett, whom he called "My Dear Brother," explaining that, "I then prefered being exchanged feeling it was my duty or be called a coward but we did not go through & never will[.] I cannot tell whether we will be allowed the oath or not as I have never inquired[.]" Bedford continued to request that Bennett research the arrangements that would need to be made, and on April 24, Bennett responded with information about how to request a release.

For most Confederate soldiers like Alex M. Bedford, the events of April finally signaled the end of the war, and while they were severely disappointed in the outcome, the month of April finally convinced them that it was time to lay down arms and return home. For a few others, though—especially for hardened guerrilla fighters or "bushwhackers," including such men as William Clarke Quantrill and Jesse James—who had grown accustomed to personal feuds, brutality, and the spoils of plunder, laying down arms would be harder to accept in the months and years to come. While most historians date the end of the Civil War to the month of April, events as early as May 1865 would make it clear that the animosities of the Civil War and of the Missouri-Kansas border war would continue for some time.